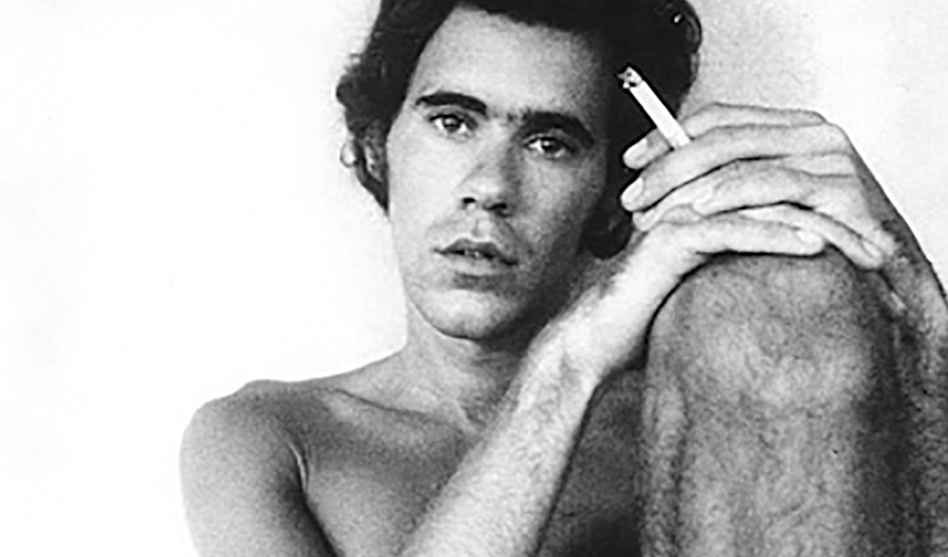

Joe Brainard, 1970″s

When I think of queer artists who loved their work more than the celebrity of it, who loved art and making art more than branding and consumerism of it, Joe Brainard is one of the first names that pop into my mind.

When I think of queer artists who loved their work more than the celebrity of it, who loved art and making art more than branding and consumerism of it, Joe Brainard is one of the first names that pop into my mind.

I was introduced to his body of work as an author in 2016 via his remarkable poetic and lyrical memoir (some even refer to it as long poem form), I

Remember. The book is pure art, entirely written in sentences, passages that all start with “I remember”:

“I remember leaning up against walls in queer bars.”

“I remember leaning up against walls in queer bars.”

“I remember when I went to a ‘come as your favourite person’ party as Marilyn Monroe …”

“I remember that for my fifth birthday all I wanted was an off-one-shoulder black satin evening gown. I got it. And I wore it to my birthday party.”

I remember thinking that I had never experienced a book quite like this, one that lived in the intersection of memoir, poetry and visual craftsmanship.

It was the kind of book that leaves the reader — especially those, such as myself, looking for a reflection in the outside world of the art inside them — wanting more.

And I quickly dovetailed into a rabbit hole of all of Brainard’s history, poetry and other works of art. What I found was someone that I, as a queer artist, should have known about long before I did.

Brainard was born in Arkansas but grew up in Tulsa, Okla. He started creating art at a young age, even making dresses for his mother. At 16 he, along with three future poets, created an art and literary magazine, The White Dove Review. This was his first real foray into public artmaking.

Soon after he graduated, Brainard moved to New York. But it was only on his second trip back to NYC after a short stint in Boston that his artist life and work began to take shape.

Brainard spent 20-plus years creating a rich body of work that included everything from poetry to collage, book design, oil paintings to theater design and comic strips.

His talent eventually led him to solo exhibitions in New York and group shows all over the world, including MOMA. And while many critics and reviews of his work loved Brainard’s ability to turn mundane everyday life into art (a trait I greatly admire, too), what struck me, what has always struck me, about Brainard’s work is how innovative, complex in its simplicity, and rooted in a trailblazing queerness it was.

His talent eventually led him to solo exhibitions in New York and group shows all over the world, including MOMA. And while many critics and reviews of his work loved Brainard’s ability to turn mundane everyday life into art (a trait I greatly admire, too), what struck me, what has always struck me, about Brainard’s work is how innovative, complex in its simplicity, and rooted in a trailblazing queerness it was.

One of my favorite poems, Life, starts, “When I stop and think about what it’s all about I do come up with some answers, but they don’t help very much.” And it ends with a paragraph that begins, “Now you know life isn’t as simple as I am making it sound.” That highlights how both Brainard and his work existed in the crux of profound simplicity amid complex questions. Life is a simply complex testimony as to how life is short and how we can “fill these 24 hours as best one can” and make each day count.

But his works that captured the essence of his queerness — and queerness in general — were his paintings, specifically, his floral paintings and his “Nancy” series. Much like Georgia O’Keeffe’s work, Brainard’s flower paintings contained a subliminal subject and study. The subject of his late 1960s and ’70s floral study were pansies, an obvious double entendre and play on the derogatory queer slang word often used in that era.

He made them colorful. Full. Prideful.

Still, it is his “If Nancy Was” series — a comic mixed media collection based off of Ernie Bushmiller’s 1938 comic strip — that, for me, really solidifies Brainard as one of the queer artist icons we should know. Over the span of a decade, he created hundreds of “Nancy” pieces that took the beloved pop-cultural figure and queered it up, camped it up. In the series, Nancy appears as many different personas, artwork and physical things: “If Nancy Was A De Kooning,” “If Nancy Was A Sailor’s Basket,” “If Nancy Was An Ashtray.”

In various articles about Brainard’s work, it is often hypothesized that he took Nancy on as an alter ego, or, as I like to call it, his drag persona. And through Nancy and his art, much like a drag queen, Brainard tried to make sense of his life and world.

In various articles about Brainard’s work, it is often hypothesized that he took Nancy on as an alter ego, or, as I like to call it, his drag persona. And through Nancy and his art, much like a drag queen, Brainard tried to make sense of his life and world.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his 1972 piece, “If Nancy Was a Boy.” In it, Nancy is lifting up her skirt to reveal “male” genitalia to the viewer.

Understanding and viewing this piece with the lens of queerness and camp that was available to us at that time — only three years after Stonewall with concepts and dialogues nowhere near as fluid as they are now — we get an artist who was entering in and performing drag in a revolutionary way, on a two-dimensional page as a comic strip character on canvas.

Mind. Blown.

Around 1979, Brainard just stopped making art for mass consumption. Some believe it was because he wanted to master oil painting and never really did due to his lack of patience — something he wrote about in a 1972 letter to Fairfield Porter — which caused him to slowly ease out of art. Some believe it had something to do with him kicking his amphetamine addiction. Still, others believe he just chose a different life instead.

Brainard was very much his art as much as his art was him. And I believe that he eventually took his own advice in the poem, Life, and devoted his daily 24 hours to “love and fun. Or things that are interesting. Or what have you. Other people are most important. Art is rewarding. Books and movies are good fillers, and the most reliable.”

Which is exactly what Joe did: He spent the last 14 years of his life smoking, reading fiction and poetry, going to movies and exhibits — basically, living his art.

On May 25, 1994, at the age of 52, Joe Brainerd died in the New York Medical Center in Manhattan of AIDS-induced phenomena. As we move into the third week of LGBTQ history month, we remember the life, art, and innovative was of seeing and creating a body of work that is Joe Brainard.