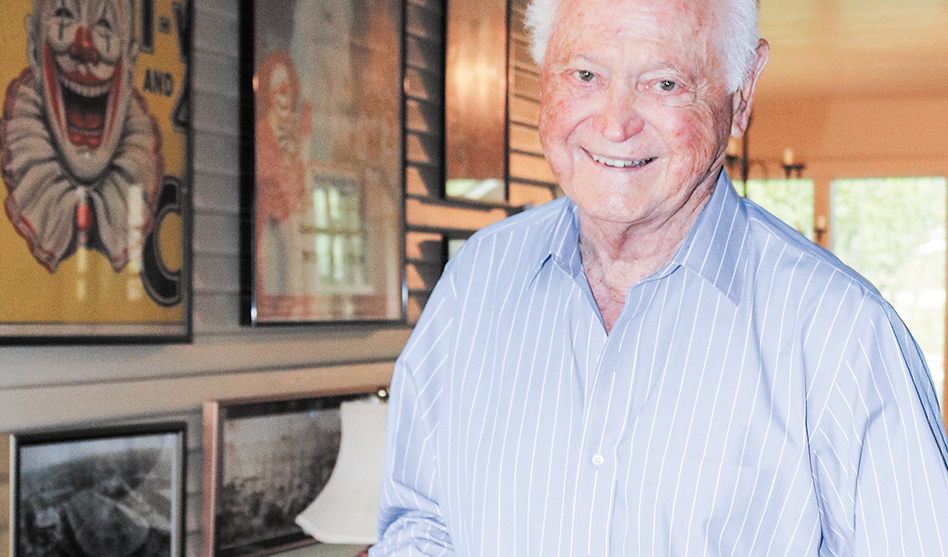

Winn Morton has spent decades crafting the most extravagant costumes ever seen. Now, at age 90, he has one last hurrah

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

When I ask Winn Morton about a lesson he has learned in his 91 years alive, he snaps at me in a pearlescent Texas drawl, more mocking than menacing. “Ninety!” he corrects. “Don’t make me older than I am.” Even a nonagenarian, it seems, has a touch of vanity.

His comparative youth barely diminishes the bona fides of his life. Morton began working at age 12 and continues to do so — at least he will until next week when, following his 40th or so engagement with the Texas Rose Festival in Tyler, he will, finally, retire. He has no idea what’s next — “One thing I won’t do is become a drunk and get fat… though I might drink a little,” he figures — but working has just become too taxing on him physically.

You can hardly blame him. Although his name might not be familiar, chances are you have seen his work. Since starting out as a gopher with Ringling Bros. in 1941, then discovering his passion for design (especially costumes), he has spent the better part of eight decades making magic. But few magicians could conjure as fantastic an effect as Winn Morton himself.

Morton’s Texas roots stretch back for generations. He still lives on an estate in South Dallas, Winniford Farms, which has been in his family since the 1850s. But if the family was land-rich, it was cash-poor. Morton grew up comfortable, but not wealthy.

And from an early age, he craved glamour and excitement.

The trope of the restless young vagabond running off to join the circus isn’t exactly true of Morton — he didn’t exactly “run away.” “I didn’t have to— my mother said ‘Go.’ I was 12, [but] it was just for the summer — two months.” He came back in the fall and went back to school in Highland Park. But formal education wasn’t his forte.

“Later I went to SMU, where I was very successful at failing,” he quips. “That’s the only place I ever failed at in my life. I was in my era of revolt. I wanted to go to Ringling school [in Sarasota] for a year.”

Morton made the move and learned even more about circus life than he had during that glorious summer less than a decade earlier. “I never liked the freak shows — I like the pretty things.” While at the Ringling school, he was taken under the wing of the great theatrical impresario John Murray Anderson (who, among other things, worked with Casa Manana in Fort Worth).

Morton made the move and learned even more about circus life than he had during that glorious summer less than a decade earlier. “I never liked the freak shows — I like the pretty things.” While at the Ringling school, he was taken under the wing of the great theatrical impresario John Murray Anderson (who, among other things, worked with Casa Manana in Fort Worth).

Anderson provided a path for Morton: He got him a job with Ringling Bros. and loaded him up on the circus train. “That’s how I got to New York from Sarasota,” he says, working stop to stop for several months. (The train ride itself was a memorable life experience. It was crowded, he recalls: “Three bunks high on each side, two [people] to a bunk.” They slept head to toe “more or less… luckily I had a good bunkmate.” Morton grins slyly.)

Moving to New York provided more valuable experiences. Morton became entranced by the spectacle of costume design early.

“In the 1950s, they had all these wonderful movies with big production numbers and magnificent costumes — that and the circus” drew him to costumes. “Costumes are all the difference in the world from clothes” — so much so, he doesn’t even know how to explain it. He attended Parsons School of Design. He met important people who also exposed him to gay life, inviting him to fabulous brunches every Sunday on Park Avenue. And he tried to forge a career.

“I would get a job [designing costumes] because of my portfolio, but I couldn’t produce fast enough and I’d get fired,” he says.

He finally landed a hit show; soon he was making “really good money at 24, but I hated it. I felt I needed to prove myself.”

That’s when he moved back to Dallas and began working for Neiman Marcus designing the windows. And then his life truly began.

Because that’s where he met Harry.

Harry was beautiful — oh my god!” Morton sighs. “He really was. He was the most popular boy and had the most beautiful body. Every Saturday, all the Neiman Marcus people would go to the Stoneleigh Hotel, where they had a swimming pool. And Harry was there with his beautiful body. I went nuts. All the guys hanging around wanted him. I was determined to have him.”

Morton played a long game of flirtation and seduction — “we weren’t virgins!” he laughs — until “I finally got him in bed. I had just got this new apartment off of Live Oak and had all new draperies. The next morning, he came into the living room and was sitting on the couch buck naked, smoking a cigarette … and he burned a hole in my new drapes! And you know what…? It didn’t matter. He was just so pretty.”

Morton was 25 when they met. They remained inseparable for the next 53 years.

“Harry used to hear people say they’d been together 25, 30 years, and he’d say, ‘Well, that’s a beginning.’ He was a mess.”

Harry — a Mississippi boy plucked by Neimans scouts to join the most prestigious retail brand in the country — was more like a force of nature, to hear the stories. They relocated to NYC, where Harry taught at Fashion Institute of Technology for years while Winn worked as a costume designer for Ringling as well as Broadway. They traveled. In 1977, they decided to move back to Dallas and quickly became ensconced in Dallas’ social scene… despite being quite obviously a couple.

“Everybody knew us as Harry and Winn — it wasn’t a question of us being out. I never came out to my folks and they were deaf, dumb and blind when it came to [my sexual orientation]. My folks would never had accepted it. I used to come home for the holidays, and [friends would ask my parents about Harry and me], and I would hear my mother say, ‘They are just friends, they are just roommates.’”

But even among Texas powerbrokers, Harry remained true only to himself. “Harry talked a lot. He’d be on the phone for three hours and I’d say ‘what were you all talking about?’ He would say ‘We were discussing a recipe.’ We’d have parties out here and we’d have a CEO come, and [beforehand I would tell Harry], You have to be nice just for one evening!’ And he would not bend! But it worked out.”

Fifty-three years together is a long time, but it wasn’t enough. Harry died about 12 years ago, and Morton still tears up to talk about it, punctuated by anger over the “fucking cigarettes” that would lead to Harry’s death (and also killed Morton’s mother).

In the decade since, Morton threw himself into his work, especially creating all the costumes and sets for the Texas Rose Festival, a three-day event held every October in Tyler that centers on a debutante pageant: The Rose Queen and her court. But now even that must come to an end.

My best years were in my 60s and 70s. I was more completely aware of myself [and my skills]. But this is my swan song.”

He repeats the phrase several times, as if saying it aloud will help in his resolve. He loves what he does and still has a lot of creativity, but “I can’t do it anymore. I like it, but I become so tired. It’s time to retire. All roses have thorns,” he jokes, “but on the whole, it’s been wonderful. I enjoy women; they are probably more interesting than men. I’m not bisexual — don’t get me wrong. But women are smart and fun to be with. But I’ll miss it.”

Organizers of the festival, which this year runs Oct. 17–20, choose a theme for its look, and for about 40 of its 86-year existence, it has been Morton’s job to execute that theme with a degree of extravagance rarely seen since the French Revolution. Only maybe a little more so.

Morton calls this year’s theme “famous women,” although technically it’s “Portraits of Inspiration.” And as a gay Texas costume designer with no more fucks to give, Morton knows it’s impossible to be too over-the-top.

He pulls out his phone to show off some of the gowns. The skirt on his Mary Queen of Scots is solid pearls. His version of Catherine the Great and Marie Antoinette are even more elaborate. All in all, he has 60 costumes to complete as well as the sets. And it’s all very pricey.

“We don’t do bunting — that’s for fucking floats,” he mocks. We do expensive.” (Asked to identify his favorite fabric to work with, Morton shoots back, “One that’s covered in sequins. You know what you do with sequins? You compound it with rhinestones. It really makes it glitter. We don’t like to be ordinary.”)

Morton’s gift for costuming even attracted the attention of documentarian Ashley Bush (granddaughter and great-granddaughter of two presidents), who ended up making a short film about Morton’s work with the festival called The Queen’s New Clothes, which has played the festival circuit this year. As much as it’s about Morton, though, it’s something else, too.

“It really did break my heart. It’s a beautiful story, but it’s really about Harry.”

And once again, Morton chokes up. It’s all over so quickly.

- Some of Winn Morton’s sketches of his designs over the years