James Laster says he wants to make amends to those he hurt

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

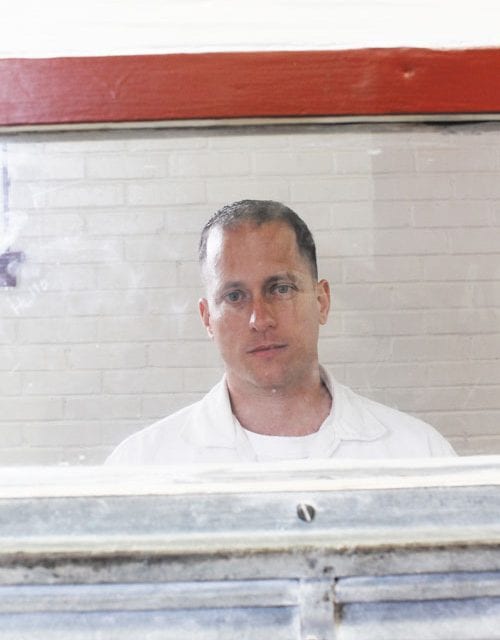

“It took 45 seconds to throw away eight years of my life,” 36-year-old James Laster said, speaking through a glass partition in the visitor’s building at the Ramsey Unit prison in Rosharon. Laster is serving an eight-year sentence at the Texas prison unit south of Houston after pleading guilty to charges stemming from the 2011 gay-bashing attack on Burke Burnett in Reno, Texas, just outside Paris.

Laster said he keeps himself busy in jail. He gets up at 4:30 in the morning and does 300-400 pushups. After breakfast, he works as a teacher’s aide in cabinetmakers class.

“I’m good at it,” he said.

He said he enjoys showing others who’ve never touched a skill saw or a drill how to use them to build furniture. He called his job therapeutic.

He said he enjoys showing others who’ve never touched a skill saw or a drill how to use them to build furniture. He called his job therapeutic.

Later in the day Laster said he works on his associate’s degree. He’s taking four classes this semester — government, history, geology and English. After dinner he spends time out in the rec yard, reads, does homework and writes. He has a TV in his cell, but said he rarely has time to watch it.

Laster was charged with three counts of aggravated assault after the October 2011 attack. He pleaded guilty to one count of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon (his hands and feet).

Burnett said everyone at the party they were attending that night was drunk. He said that when a fight broke out, several people — including Laster — attacked him, leaving him with cuts on his face, neck and arms from a broken bottle, contusions and burns resulting from when he was thrown or fell on a burning 55-barrel drum used to heat the barn.

Laster takes exception to some of the claims, saying Burnett wasn’t thrown onto a bonfire, as some news outlets reported, but fell on the burning drum, and that at least some of what police called stab wounds were from Burnett falling on his own broken beer bottle.

But Laster willingly takes responsibility for his part in the attack on Burnett, acknowledging that as he hit and kicked Burnett, he also called him “faggot,” which led to hate crime charges being leveled.

Another attacker, Micky Joe Smith, who was 25 at the time, was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Charges were dropped against a third man, Daniel Martin, after Laster told police Martin had already left the party when the fight broke out. Burnett said he remembers more than two people attacking him, but no one else was charged.

Laster wrote to Dallas Voice in January. In his letter, he said he wanted to make amends to the LGBT community. We get letters from inmates all the time, but there was something introspective and interesting about Laster’s missing. Not only was his contact with us timely, coming as it did within months of a rash of attacks on gay men in

Oak Lawn last fall, he also seemed to be taking responsibility for his actions. So I arranged a visit with him through the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

The prison wasn’t easy to find. Google maps sent me to the wrong place — or more accurately, the map stops about four miles short of the prison’s location. But I was able to find someone who gave me accurate directions.

Laster was a little rattled as he came into the meeting room and sat behind a partition of glass and metal mesh. A guard had gotten him out of his class and brought him to the warden’s office before escorting him to our meeting. He said he’s trying to stay out of trouble, so a trip to the warden’s office can be quite upsetting.

As a result, we were both a little anxious as we began to chat and started by just introducing ourselves to each other.

“I love to write,” he told me. “If I’m frustrated, I can get a pen and paper out. Sometimes I write five pages.”

In part, he said, his writing is what got him to Ramsey Unit. He began taking classes before being moved to the South Texas location. Ramsey Unit is the only prison in the Texas penal system that not only allows a student to get an associate’s degree, but lets them advance their education to earn bachelor’s degrees and even master’s degrees.

Several hundred inmates at the unit are taking classes, Laster said. After he’s released, he’ll be responsible for reimbursing the state for his tuition.

Laster insists he’s not the same person he was when he entered prison. Burnett, reading Laster’s first letter, agreed, saying he didn’t recognize him from before, either.

“For the first two years, they punished me,” Laster said about his current sentence. “Now, I choose to try to do something productive and become a better person.”

He was first incarcerated in a prison near Palestine, where he described the treatment of gays and child molesters and said, “You see how they’re treated. You see the mentality. It begins to mold you.” Then, he said, he decided he was going to act like the kind of person he wanted to be treated as, and his behavior paid off.

James Laster, above, sits behind a glass partition during the interview for this article. Burke Burnett, here, seen just after he was attacked.

Laster said he’s thankful to be at Ramsey, where fighting isn’t tolerated. He said prisoners who are repeatedly caught in fights find themselves on a bus for another unit.

How did he get here?

When Laster was 15, his mother died. He had no relationship with his father, at the time, and no place to go. Child Protective Services had no options for him.

So some friends took him in and that’s when he got involved in dealing drugs. Within a few months, Laster was arrested for possession with intent to distribute and put into the juvenile detention system, where he was housed with violent prisoners.

“There should be some alternative for non-violent crimes,” Laster said of his first incarceration. “The state surrounded me with violence. All they did was prepare me for this” future of crime and violence.

But Laster is quick to stress that he isn’t trying to dodge responsibility for his actions. “That’s not an excuse, but an explanation,” he said of his assessment of juvenile detention.

When he was released from Texas Youth Commission, Laster lived first in a group home in Marshall and then with his sister, who’s less than a year older than he is. He described his work record outside of prison as spotty, and noted that he spent time in jail more than once, and when he was out, he often supported himself by selling drugs.

In his mid-twenties, Laster had a son, gaining full custody when the child was 18 months old. Laster raised his son himself — right up until the time his son was 7 and Laster was arrested for the attack on Burnett.

His son is still a source of great pride for Laster, whose eyes twinkle as he talks about his boy. “I taught him how to read and write,” he said. “He plays the trombone. He’s in National Honor Society and he’s extremely smart.”

Laster described what he called the best memory of his life — sitting with his son on the sofa, eating cookies and watching Sponge Bob Squarepants — before remorsefully acknowledging that he threw that away. “I chose this [violence and a prison sentence] over my son,” he said.

Laster gets to talk to his son on the phone from prison, but not often enough, he said. Prisoners can only call approved numbers, which must be land lines or cell phones that are billed monthly. His ex has a cell she pays monthly, so that number can’t be on his approved list. That means he only gets to talk with his son when the boy visits Laster’s aunt.

Laster recalled one instance when his son once asked him, “Why are you in there?”

“I told him I was at a party,” Laster said. “I told him I made a very foolish decision and I assaulted someone. I hurt this guy.”

“How hard did you hurt him?” his son asked.

“Pretty bad,” he said, adding that he apologized to his son for not being there for him.

Laster said his son was always a good kid he never had to spank, which means his son has “never seen the violent side of me.” That makes him happy, Laster said, because his violent side scares even him.

“One of the worst feelings in the world is not being in control,” he said. “I don’t like that I’m subject to hurt someone.”

He said that violent side only comes out when he’s drunk or high and he wishes there was counseling available. Since there isn’t, he has taken a course in prison called Christians Against Substance Abuse. But every time they were about to talk about an issue, like anger, the subject changed to the Bible, and since, Laster said, he’s not particularly religious, those classes didn’t help him very much

But classes did encourage him to read some self-help books that were helpful.

“I was mad at myself, at everyone else, at the system,” Laster said of what he has learned about himself. “My go-to feeling was, ‘I don’t care.’”

He described the night of the attack as one that began badly and quickly got worse. Already drunk, he got a ride to the party rather than drive himself. At one point he left and says now he wishes he hadn’t returned.

What’s next?

Laster had his first parole hearing last year. He described it as 10 minutes with people who wouldn’t be voting on whether to grant him parole.

He said they asked him: “Why did you stab this person so many times?” Laster disputed that characterization, telling them that he was in prison for assault with his hands and feet. But, he noted, the parole board sees all the charges as well as his full criminal history, which includes earlier drug charges and two DWIs.

Laster insists he’s planning to remain sober. That’s why, when he’s released, he doesn’t want to return to Paris where he’d be surrounded by people who are still doing drugs.

“My sobriety is very important to me,” he said several times during our visit.

In prison, among other skills, Laster said he has learned welding and hopes to find a job in that field when he is released. He also hopes to make amends to his son for not being there for him during the years he was locked up.

If he serves his entire sentence, Laster will remain in prison until Nov. 2, 2019.

Final words

Before I left Dallas, I asked Burnett if he had a message for Laster. He said nothing in particular he wanted me to relay, but told me I could tell Laster anything I thought was appropriate.

So I told Laster that after the sentencing, Burnett took a year to recover physically and emotionally, but now he’s living near Dallas, has done a lot of good in the community helping other attack victims and has a very happy life.

During the two hours we spoke, Laster repeated that he took full responsibility for his actions, and stressed that he didn’t want anything I wrote to sound like he was making excuses.

So, just before I left the prison, I asked Laster if he had a message for Burnett. Tears came to his eyes, and he thought for a moment.

“I apologize,” he said.

He tried to find additional words, then shook his head.

“Tell him I apologize.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 4, 2016.