Shawna Woods tried to help her stepbrother, but a ‘brutal’ upbringing and mental illness took their toll in the end

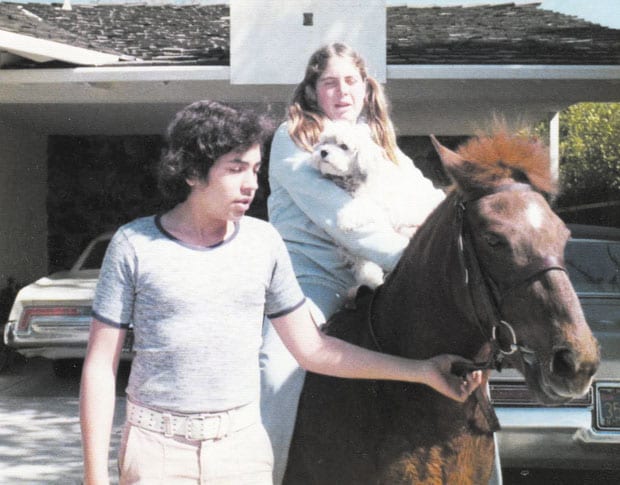

James Torres, who used the name Anthony Bertroni when he moved to Texas, underwent experimental treatments for AIDS in the early 1980’s (below). His sister, Shauna Woods pictured with him when they were teens, said his mother abandoned Torres when he came out as gay.

DAVID WEBB | The Rare Reporter

CEDAR CREEK LAKE — For two weeks after a law enforcement officer shot him to death in a day-long standoff, James Frederick Torres, also known as Anthony Bertoni, lay in a funeral home, waiting for his next of kin to sign documents allowing his body to be cremated at county expense.

In death, Torres remained alone and adrift, much the same as he had for at least the last decade of his life, maybe much longer.

Law enforcement officers knew the identity of Torres’ stepsister who had attempted to help him in recent years. But they knew little else about the reclusive, 56-year-old man who lived on Highway 274, on the Henderson and Kaufman county line, in a small, dilapidated house surrounded by an eight-foot chain link fence. Outside the fence sat an old, broken down car plastered with disturbing signs, on which were written “Murder” and “Suicide,” and incoherent letters taped on the inside of the windows.

After his death, Anderson and Clayton Brothers funeral home staff and public officials struggled to unravel the mystery of Torres’ life, so they could put him to rest and discover the evidence needed to close the Texas Rangers investigation into the day Torres suffered his last psychotic episode.

He started that day by firing a shotgun at a neighbor, then barricaded himself in his home for eight hours. He ultimately walked outside shooting a gun, and a bullet from a Texas Department of Public Safety marksman perched on the roof of the Calvary Baptist Church across the highway struck him down in what seems now like an act of “suicide by cop” — what it’s called when a suspect deliberately acts in a way that an officer is forced to shoot him or her.

He started that day by firing a shotgun at a neighbor, then barricaded himself in his home for eight hours. He ultimately walked outside shooting a gun, and a bullet from a Texas Department of Public Safety marksman perched on the roof of the Calvary Baptist Church across the highway struck him down in what seems now like an act of “suicide by cop” — what it’s called when a suspect deliberately acts in a way that an officer is forced to shoot him or her.The standoff closed down Highway 274 and County Road 4044, disrupting the small Cap City community of the Cedar Creek Lake area for 36 hours. Afterwards, everyone struggled to make sense of what had happened. Few people in the community, except for Torres’ immediate neighbors, knew that anyone even lived in the house. But clues begin to emerge in conversations with his stepsister, Shawna Wood, who never quit caring for the distraught, troubled man whom it is now known suffered from what is believed to be paranoid schizophrenia.

Wood, who lives in Oregon, said she visited with her stepbrother in 2010 at the house in the Cap City community where he died, and she realized then he suffered from delusions that frightened her. She said at the time of his death he lived in the house with no running water and 16 cats to keep him company. He suffered from a failing liver and kidneys decimated by a 35-year-long HIV infection and early experimental treatments. He only left the house to shop at Walmart at 3 a.m., wearing mirrored sunglasses. At times Torres called himself Jesus Christ, and at other times he referred to himself as being controlled by demons, she said.

Torres spent time in a Dallas psychiatric hospital in 2014, after law enforcement officers with whom Wood cooperated convinced him to admit himself voluntarily, and he showed improvement. Unfortunately, he quit taking the medication administered at the hospital upon release, and he relapsed, his stepsister said.

Wood said law enforcement officers attempted to talk Torres into returning to the psychiatric hospital, but he refused. They said his guns could not be legally confiscated, even though concerns about him being a threat to himself or others arose, she said.

His stepsister stayed in contact with Torres until his death, sending him food by way of public carriers because he feared leaving the house. He thought people wanted to hurt him because of his sexual orientation and HIV-status, and he imagined various conspiracies being orchestrated by the people who lived around him, Wood said, adding that efforts by a local pastor and others to help him failed.

After his death, Wood, one year younger than her stepbrother, knew what few other people did. She was not next of kin to the man who had moved to Texas eight years ago from Palm Springs, Calif., after changing his name from Torres to Bertoni. Torres’ mother, whom he last saw at age 17, likely was still alive and ultimately responsible for all decisions, and the mother was the heir to anything belonging to her son, such as the house he bought on EBay sight unseen.

Wood said after Torres died she had no idea of her stepmother’s whereabouts. “I haven’t seen her or talked to her for 20 years,” Wood said. “And I don’t want to talk to her now. I never cared for her.”

Torres’ adoptive mother divorced her first husband, and in 1970, when Torres was 11, she married Wood’s father, a prominent doctor in Freemont, Calif., Woods said. Wood’s father, having been recently widowed when his first wife died of cancer, allowed Torres’ mother to rule the household in a miserly, vindictive way, Wood said.

Wood described her stepmother’s treatment of both her and Torres as “brutal,” saying the woman changed her home in ways that upended her whole life. She said her stepmother taped a picture of a pig on the refrigerator and told her she resembled the farm animal because of her weight, Wood added.

“’Bitch’ would be too kind,” Wood said in describing her stepmother. “When my dad married her in 1970, the first thing she did was forbid me from visiting with my nanny, this wonderful Italian lady who promised my mother on her death bed that she would take care of us. After that, we raised ourselves. Next, I came home from school and my poodle Taffy was gone. She said she ran away. Years later one of the neighbors told me she put Taffy in the car drove her somewhere.”

At age 15, Wood said, she went away to boarding school in Florida and finally began to enjoy life again. But her departure ended the close relationship with her stepbrother, Torres. She said that their relationship had become so close at one point that her stepmother insisted on Wood getting a physical examination to ensure no sexual activity had occurred between the children, Wood said.

“I couldn’t take the bullshit anymore,” Wood said of her reason for leaving. “I found out as an adult I paid for it myself with Social Security because my mother was a pediatrician. But I can’t believe my Dad was an obstetrician and gynecologist and couldn’t pay for it. After marrying her, it was like living in poverty in a wealthy household.

It was just so bizarre.”

Wood said her father wound up divorcing Torres’ mother in 1995 after 25 years of marriage because he came to distrust her. After he died, Wood discovered there was almost nothing left of his estate, and she inherited only enough to buy a house.

“She ended up with nearly everything because at the time he had Parkinson’s, and he didn’t fight anything as he didn’t have the energy,” Wood said. “For years they had separate property, but in 1978 after he became Mormon, he put her name on everything. Essentially, anything that was my mother’s became hers.”

For several years Torres quit speaking to Wood, angry that she had inherited money from her father while he likely would never get anything from his mother. “It didn’t really make sense to me,” Wood said.

Wood said Torres’ mother, a devout Mormon, wanted nothing to do with her adopted son when he got older. He came out as gay as a teenager and contracted HIV in about 1981, when many people referred to the illness as “gay cancer” and scientists had not yet discovered the human immunodeficiency virus and coining the name “AIDS.”

Wood said when her stepbrother was first hospitalized with an HIV-related sickness at a Freemont hospital, neither her father — who delivered babies at that hospital daily — nor his mother ever visited him, and the nurses there treated him like a leper.

“They practically slid his food trays under the door,” Wood said. “He was put in quarantine.”

Wood gave the funeral home, a title company lawyer representing a potential buyer of Torres’ property and law enforcement officers her stepbrother’s real name and the name of his mother, who along with her first husband, a man of Argentine descent, adopted Torres as a baby in Stockton, Calif.

None of the people searching for Torres’ mother seemed to be able to determine if she was alive or to locate her. But an Internet search by the Dallas Voice found her living, at age 84, in Logan, Utah, and about to move into an assisted-living facility. The woman, who before retirement ran a school that taught medical office procedures, also authored two technical books and one murder mystery that are available on Amazon.com.

After sending emails to eight addresses listed for Torres’ mother, at least one went through and a friend of hers responded by phone to find out what the inquiries concerned. The friend put his mother on the phone, and the mother participated in two on-the-record interviews over a two-day period.

During those interviews, Torres’ mother said she was unaware of his death, and that she had not talked to him since he ran away from home at age 17.

“He just didn’t like living with us,” his mother said. “We were a religious family, and he didn’t like going to church. We looked for him for years. He never came home.” She acknowledged her church taught against homosexuality. “It probably did,” she said. “I think most churches do.”

On the second day, the mother called back, demanding under threat of legal action that her name not be used in any story about her son because of the potential embarrassment being associatd with Torres and his troubled life and death could cause her.

“I have relatives living in Texas and friends all over the country,” she said. “I don’t want them to know about it.”

When advised that the funeral home needed permission to cremate his body, she asked, “Who is going to pay for it?” After learning that Torres had owned a home that sat on commercial property that someone wanted to buy, she asked, “Who will get the money?”

The potential buyer told Torres’ stepsister that the dead man’s mother called him the same night she learned about his death and the existence of his property, demanding a substantially higher price than he was willing to pay, according to Wood. When he explained the house would have to be torn down because of its deteriorated state, the buyer told Wood, Torres mother said she planned to immediately list it with a real estate agency if he failed to meet her price.

Torres’ mother said as a toddler her son seemed hyperactive, almost angry, bouncing and banging his hands on the bedding. As a young child he and a friend started a fire in the garage, she said, and he and some friends stole a vehicle as teenagers and drove it to another state. Wood offered a different story, though, saying the vehicle belonged to Torres’ adoptive father, and that it was more of a prank and a lark than a theft.

Still, his mother said, “My first husband and I wondered if there was something wrong with him.”

When asked if she disowned Torres because he was gay and HIV-positive, she said, “Who told you that?” Advised that Torres told several friends of their estrangement and the reason for it, she said, “I don’t remember that. I don’t remember things well anymore. I have a disability.”

Torres’ mother said she remembers her adopted son was taunted at school by kids who accused him of being black because of his dark coloring. In fact, he was of native Hawaiian descent, she said. “He came home from school upset about that,” she said. “I told him he wasn’t black, but it bothered him.”

His mother said she heard her son was living in San Francisco in his 20s with a psychiatrist, and she heard that he was gay and later that he was sick. “I didn’t know what was wrong with him,” she said.

Wood claimed that her stepmother and father never looked for Torres, and that they knew well the nature of his ailments. His mother abandoned him, she said. “My God, even in death she will deny the connection,” Wood declared, after hearing her stepmother’s version of Torres’ life.

Wood said one of her biggest regrets now is that Torres will only be remembered for the tragic way he died and his suffering from mental illness and HIV-related issues.

“He was fun,” she said of her stepbrother. “He was the best. I will always wonder if Jimmy’s life would not have been so tragic if she had not abandoned him. ”

Lisa Kaii, a lifelong friend of Wood’s and her stepbrother, confirmed the account of Torres as a teenager and his mother. “He was so much fun,” Kaii said. “He was always laughing and making us laugh. He made up jokes and songs all of the time. His mother was crazy. We didn’t like to be around her.”

Wood said her biggest goal now is to see her stepbrother’s body treated with the dignity he deserved in the absence of a funeral or memorial service. She received good news to that end March 1.

“We’re almost there,” Wood said. “I just received an email his mother signed permission to cremate. Maybe soon he’ll be at peace. Jimmy’s life did matter.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 4, 2016.