During the years of the AIDS epidemic, drag queens raised millions of dollars that was used to establish agencies and even buy dog food

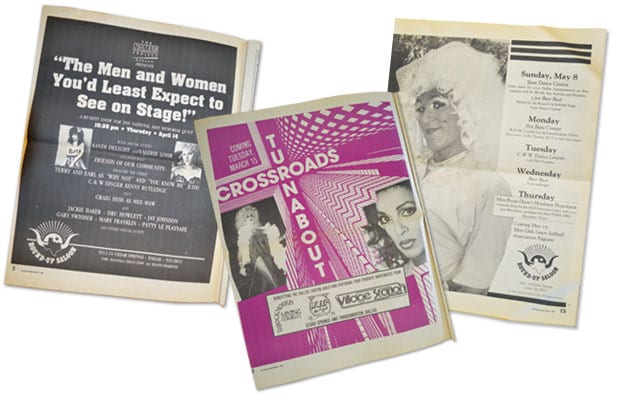

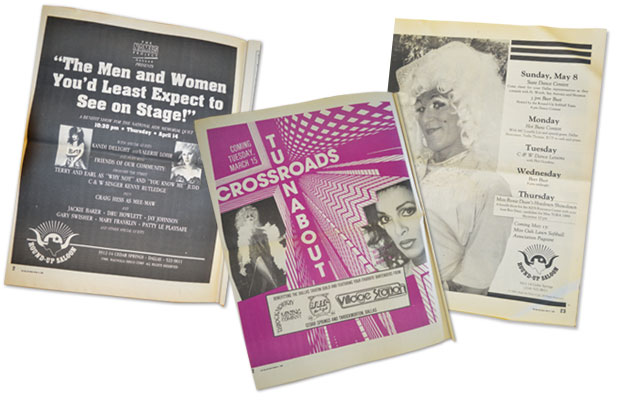

THE WAR YEARS | Advertising from 1988 editions of Dallas Voice shows the work the drag queens were doing to raise money to fight AIDS and fund the AIDS agencies.

STEVE RAMOS | Senior Editor

DAVID TAFFET | Staff Writer

It was our Pearl Harbor. And they were our Marines. Yet there is no memorial, no yearly observance that commemorates the work of a group of people who stepped on to a battlefield that was quickly being littered with our dead. During a time when our own government was silent and inactive, some members of our community weren’t. They fought back, and they did it in heels, wigs and a prodigious amount of makeup.

In the early 1980s when the AIDS epidemic slammed into the community and started killing us, some gay men and trans women shook off the shock and went into action. In almost every gay club in Texas, performers stepped on stage in drag and raised money to fight AIDS. Lots of money.

For those who didn’t experience the AIDS crisis, imagine a time during the late ’70s and early ’80s when the clubs were full of liberated men and women, celebrating without an inkling of what was coming around the corner. The release from the confines of small-town biases and religious shackles fueled the party.

And then it hit.

“Lord, I remember how it hit,” Gary Williams said. “It’s like we were partying one month and then burying people the next. It hit us hard and fast. But you know what I remember so clearly, so vividly? I remember how the drag queens started raising money to fight AIDS.”

There isn’t a granite wall where the drag queens’ names are etched, but Williams said there should be, so great was their contribution in the fight against the epidemic. Donna Day, Patty le Plae Safe, Donna Dumae, Kandi Delight, Whitney Paige, Tasha Kohl, Naomi Sims, Edna Jean Robinson and the names of dozens of other performers recall the years when the drag queens looked out across a ravaged community and sang for dollars.

One dollar became 10. The 10 dollars became a thousand, and the thousand dollars became millions. On that foundation, other community leaders built Oak Lawn Community Services, AIDS Services of Dallas, AIDS Arms, Bryan’s House, AIDS Interfaith Network and others. The sick and the dying had a place to get medical help, food, a place to live and a place to rest.

“But there was more to it than that,” Dumae said. “In those days, we were fighting more than AIDS. The cops were still raiding the clubs and harassing us. They’d come in completely covered up and make a big show of it, protective clothing, like there was something in the air, and they’d catch it. They’d call us names. But we still went on. We still put on the shows to raise money. We had to.”

Dumae started performing in 1982 in Fort Worth and still performs two major shows a year that benefit AIDS Services of Dallas. She, like most of the other performers, have no idea how much they’ve raised over the decades, but Don Maison, President and CEO of ASD said, there were times when Dumae and other drag queens “saved our butts.”

“I didn’t have a single nurse or home health aid,” he said. “Sometimes there was barely enough money to pay the electric bill. He relied on Mark Shekter’s Meals on the Move for breakfast and the Supper Clubs started by Kay Wilkerson to provide dinner. The money for meals not otherwise provided often came from funds raised in the bars.

When Maison started working at ASD in 1989, the agency’s total budget was $200,000, and that included the only government money he was receiving — $25,000 from the Texas Department of Health and a multi-year Robert Wood Johnson demonstration grant.

“This was before HOPWA and before Ryan White,” Maison said, referring to Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS and the government funding of various other AIDS services.

Patti le Plae Safe said she has no idea how much money she raised for the AIDS organizations over the years.

“Honey, I stopped counting,” she said. “It’s in the seven digits.”

At one point, she was performing up to five shows a night, seven nights a week. On a typical night, Patti said she’d start at TMC and then cross the street to the Round-Up Saloon. Then she and a couple of other drag queens would jump in a pick-up truck and drive over to the Eighth Day on Fitzhugh Avenue. And they still weren’t finished for the night.

They would head over to the The Wave on Maple Avenue and then circle back to Cedar Springs Road where they’d finish at the Green Parrot, performing on the top of a pool table. Proceeds from one of the shows would benefit the food pantry, another would go to ASD and another to Byran’s House.

“We just wanted to help everybody,” Patti said.

And they did — for more than a decade. Patti, who was on the board of the Foundation for Human Understanding, now called Resource Center, said Bill Nelson would mention that donations were down at the food pantry and could Patti help. Nelson was one of the early Dallas activists. Patti said one person would coordinate the effort by calling other drag queens and singers like Linda Petty or performers like Buddy Sherman.

“Everyone said yes,” Patti said.

This went on for more than a decade, although some drag queens performed longer.

“We were still pumping shows hard in ‘’93, ‘’94,” Patti said, “and into 1995 when I was Miss Gay America.”

Donna Dumae remembers raising money for the needs that AIDS created.

“People with AIDS were being burned out of their homes, kicked out of their apartments and fired from their jobs,” she said. “We even raised money so people could buy dog food. There was so much need.”

The more people died from AIDS, the more the drag queens cranked up the theater.

“It was all about being big and bold,” Donna said. “We had to be showy and bigger than life — big boobs and big hair. You have to remember, doing drag was even illegal in those days.”

That’s another reason Williams said there should be a memorial that honors the drag queens’ contributions.

“They were the brave ones,” he said. “They were out there on the forefront, storming the beaches and getting in the cops’ faces when our bars were raided. They didn’t back down, and we’re alive today because they didn’t back down.”

The AIDS epidemic also took its toll on the drag queens. Their numbers diminished just as their audiences did. Patti said her friends were dying one after another.

“Kandi Delight was in a show with me one week, and the next week she was dead,” she said. “Performing was very, very emotional.

War unites a community, and the drag queens were of one mind in the fight against AIDS. Patti said the performers cared about one another.

“They’d lend you shoes and dresses,” she said.

Michael Doughman, executive director of the Dallas Tavern Guild, has been raising money for AIDS and LGBT organizations in Dallas since 1983.

“Easily over a million and a half over the years,” he said.”

His first performance after he moved from Reno was at the Round-Up Saloon.

“We were just trying to raise money for someone who was sick,” he said.

During those dark days of the AIDS crisis, Doughman said the drag queens added another much-needed element to the bleak landscape — they made people laugh for an hour or two.

Doughman found out he was HIV-positive in 1985. When AZT was approved, he went on the medication for two weeks. It made him sick, so he switched to vitamins and herbs.

“I’m alive for a reason,” he said, “I need to be doing something worthwhile.”

The names of many of the drag queens who saved us are legend, but Patti and Donna said their friends contributed to their personas. Donna’s friends came up with her drag name, and Patti said she also had a lot of help and input.

“It takes a village to put on a show,” Patti said.

That village included not only the performers, but the bars and all the people who went out and donated one dollar at a time.

“It takes a village,” Patti repeated. “A very large and partially demented village.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 25, 2014.