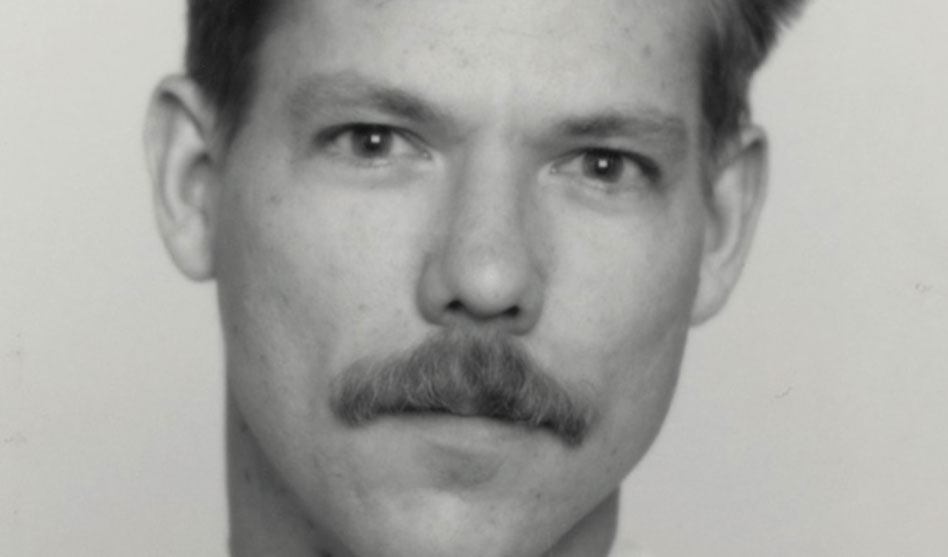

Bruce Monroe in his DGLA portrait

Bruce Monroe, one of Dallas’ LGBTQ rights and AIDS pioneers, has died

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

Bruce Monroe, one of the early HIV and LGBTQ rights champions in Dallas, has died at the age of 65. For the past seven-and-a-half years, he battled a condition known as ataxia that left him unable to walk or to talk without great effort, but his mind remained clear. He communicated by typing into his phone with his thumb.

In 2020, Monroe was given the Raymond Kuchling Award by Black Tie Dinner for his years of service to the community and his activism. Friends read the acceptance speech that he had written.

In a video made for The Dallas Way history project and later transcribed, Monroe described himself as a military brat born in Roswell, N.M. He graduated from Texas A&M, then moved to Houston to build sets for the Houston Grand Opera and Houston Ballet. He came out in 1981 while working there.

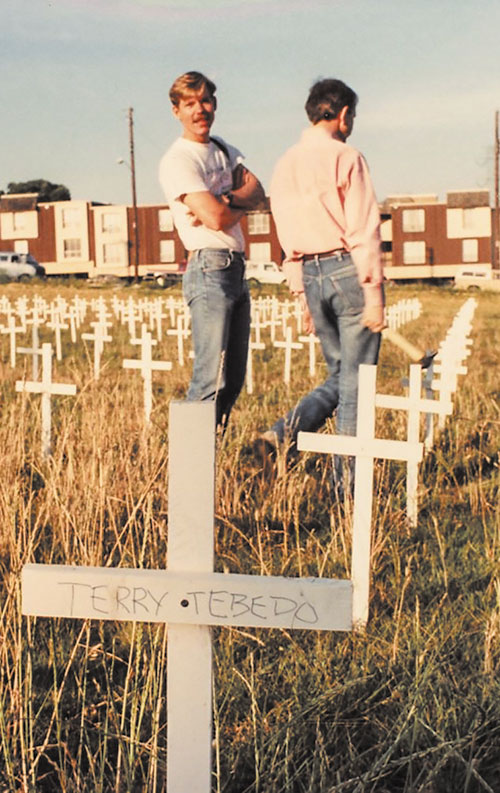

Bruce Monroe, left, standing in the field of crosses on the corner of Cole and Lemmon in 1988

His next job was with a Florida-based company installing satellite TVs around the Caribbean and South America.

But when that company went bankrupt about a year later, Monroe moved to Grand Prairie, landing a job in the fundraising department at KERA.

Monroe joined Dallas Gay Alliance, now known as Dallas Gay and Lesbian Alliance, when a date brought him to a meeting. He began working on the organization’s publications and quickly rose to become its president.

DGA had started a new project to help a growing number of gay men living with AIDS. The organization was called the Foundation for Human Understanding and is now known as Resource Center. FHU hired John Thomas, another well-known AIDS and LGBTQ activist, as its executive director, and Monroe became its president, helping spin it off from its parent organization.

“Bruce led us: chalking ‘bodies’ on the street, dumping HIV mannequins off the roof at Parkland Clinic, kissing at city council meetings and literally fighting — FIGHTING — for HIV care,” Jamie Schield wrote about Bruce Monroe on Facebook. Schield was one of Resource Center’s first employees and later served as its executive director.

Bruce Monroe speaking at Outrageous Oral at UNT in Denton in 2013. (Photo courtesy of Junebug Clark, University of North Texas)

As president of FHU, Monroe dedicated himself to providing services — a food bank for people who had lost their jobs due to HIV and had no means of support, and the beginning of its clinic.

In other cities, medical facilities offered pentamidine mist to stave off pneumocystis pneumonia, the AIDS-related pneumonia that was taking so many lives at the time. No hospital or medical facility in Dallas would offer the preventive treatment, so Resource Center — under Monroe’s leadership — acquired the equipment and the medication that nurses Penny Pickle and Pam Clayton then administered. They treated about 100 people per week.

Monroe also co-founded an organization called Gay Urban Truth Squad — better known as G*U*T*S — to protest the lack of care for people living with AIDS in North Texas. Founded before ACT-UP, G*U*T*S later joined that larger, national group.

Among the protests that attracted hundreds of people was one staged when President George H.W. Bush was speaking at the Dallas Convention Center. G*U*T*S held a die-in right outside the main entrance. Half of the protestors lay down on the sidewalk that cold winter evening as the rest drew their outlines in chalk then, inside the outline, inscribed the name of someone who had died of AIDS.

Bush never acknowledged the protest.

Bruce Monroe, left, presents an award to Dallas Police Chief Ben Click during the Festival in Lee Park following the Alan Ross Texas Freedom Parade.

Another AIDS memorial Monroe helped create was on a landfill on the corner of Cole and Lemmon avenues. A developer had begun a project and excavated a hole for the parking garage before going bankrupt. The city left the hole untouched for several years, but when it began to threaten property and streets around it, at a cost of half a million dollars, the city filled in the hole. G*U*T*S built 500 crosses — a number equalling the number of cases of HIV in the city at the time — and planted them across the field.

What gained the most attention in that protest was the one cross that bore the name “Terry Tebedo,” a well-known activist who had recently died of AIDS.

That field of crosses brought attention to the fact that while the city of Dallas had spent half a million dollars to fill in a hole, it had spent about one-tenth that amount — only $55,000 — on HIV that year.

After losing his position at KERA — due to what he said was homophobia at the station — Monroe was hired as associate director of membership at the newly-opened U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. About two weeks after he arrived, his immediate boss resigned, and Monroe became director of membership.

He used skills he learned as president of FHU — thank-you notes got out promptly, donors received benefits like tickets to the museum that were hard to come by in its early days — and he got involved in the local AIDS organization’s food pantry.

While in D.C., Monroe learned that he was HIV-positive. His insurance at the museum wasn’t very good for someone with a catastrophic illness, so when he was offered a position at the National Park Foundation — a job that offered excellent insurance — he took it. When he had been working there about two years, doctors diagnosed him with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The Stonewall Professional Business Association board. Bruce Monroe is fourth from right.

Monroe went on disability, was eventually cured of his cancer and moved back to Dallas. He decided to begin a new life as an artist and began studying at Brookhaven College. He took 136 course-hours, mostly in his preferred medium of silk screening.

From there, he moved to Tampa to do graduate studies at University of South Florida and became a teaching assistant and then an instructor. During this time, he participated in a study-abroad month in Paris. While there, he got to participate in an ACT UP die-in at the Bastille.

AIDS activism drove Monroe’s art. He had a one-man show in Tampa entitled I Thought You Were Dead. His thesis sculpture of a body representing the immune system was displayed at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and is now in a private collection.

After three years in Tampa, Monroe returned to Dallas where he was a co-founder of The Dallas Way and created its oral history project, Outrageous Oral.

Resource Center CEO Cece Cox said her favorite memory of Monroe was when he attended the groundbreaking for the Resource Center’s new building on Cedar Springs Road. Although already stricken with the illness that eventually took his life, he was able to turn a shovel-full of dirt from his wheelchair.

Monroe was brought to the groundbreaking by three friends — Ron Allen, Mark Rogers and Deb Elder.

“I was always struck by the amount of love Ron, Mark and Don Maison and others showed to Bruce,” Cox said.

“He lived so long because of their care, love and attention. They did it purely out of love and friendship, and they kept him alive.”

Allen said, “Bruce really cared for people. Whether it was marching on Parkland to demand treatment for people with AIDS or making sure the food pantry was stocked, no one will ever know how many lives he saved.”

Cox said she’ll remember that no matter what was wrong, Bruce was always in a good mood.

“He always said something kind about Resource Center,” she said. Even when they disagreed, “he took the time to encourage me and told me Resource Center is doing things [its founders] only dreamed about.”

And while Monroe had his serious side, he wouldn’t want a story about his life told without a laugh: “Bruce found joy through the struggle,” Cox said.

And that reminded her of the story Monroe told that launched Outrageous Oral. Over the years a number of versions of this story have been out there. Here’s one:

In the early 90s, Bruce flew with a group of about 10 friends to Houston for an afternoon Halloween party. When they arrived in Houston, they had time to get into drag for the event. But that evening, back in Dallas, they were attending an HIV fundraiser, and there was no time to change back, catch their flight and get into drag again. So — long before there was a TSA checking IDs — 10 men, each named Debbie, flew home on Southwest in drag.

And if they were going to do that, they decided to have some fun. Instead of sitting together, they sat near each other, each taking the center seat between two businessmen. The businessmen tried to mind their own business, mostly burying themselves in their newspapers.

“Um, Debbie,” one of them, who was pretending to do a crossword puzzle, said in a loud voice.

“Yes, Debbie?” Debbie answered.

“What’s the capital of Wyoming?” the first Debbie asked.

“Um … W?” said the second Debbie.

Businessmen hiding behind their newspapers were convulsing in laughter. One reached for a cigarette, but Monroe warned him lighting it might be dangerous. Pointing to the wig he was wearing, Monroe noted, “Ten cans of hairspray.”

Finally, one of the men put his paper down, and said he’d have a story to tell his grandchildren.

Great tribute to such a wonderful man. Dallas is a better place because of Bruce.