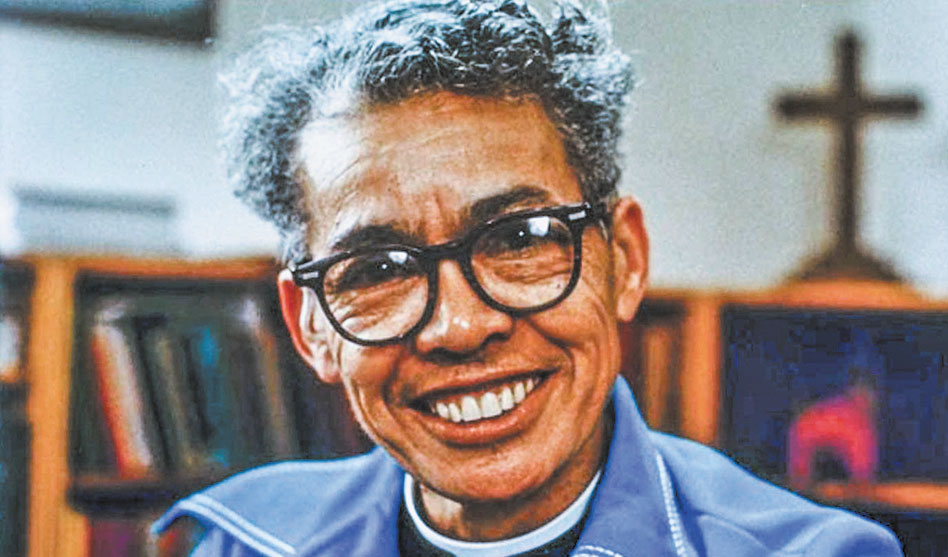

Pauli Murray seated in her study. (Image source: Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute)

Betty Friedan wanted to distance feminism from lesbians, but it didn’t work

VICTORIA A. BROWNWORTH

Courtesy of the LGBT History Project

As the website for The National Women’s History Museum notes, Betty Friedan cofounded the National Organization for Women and was “one of the early leaders of the women’s rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Friedan’s best-selling 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, “gave voice to millions of American women’s frustrations with their limited gender roles and helped spark widespread public activism for gender equality,” the website notes.

A year later, the 1964 Civil Rights Act banned sex discrimination in employment. But the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission wouldn’t acknowledge the sex-discrimination clause, effectively nullifying the Civil Rights Act’s addition of gender. As NWHM details, Freidan’s groundbreaking book “helped transform public awareness” of such discrimination and propelled Friedan into the leadership of the nascent women’s liberation movement where she was often referred to as the “mother” of second wave feminism.

From-left,-Linda-Rhodes,-Arlene-Kisner-(sometimes-misidentified-as-Arlene-Kushner),-and-Ellen-Broidy-participate-in-the-_Lavender-Menace_-action-at-the-Second-Congress-to-Unite-Women,-in-Chelsea-on-May-1,-1970.-(Photo-by-Diana-Davies-f

Then Friedan, Pauli Murray and Aileen Hernandez co-founded the National Organization for Women in 1966. Friedan was NOW’s first president and authored NOW’s mission statement: “…to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.”

Among NOW’s perspectives were “securing the enforcement of anti-discrimination law; gaining subsidized child care, abortion rights and public-accommodations protections; and passing the Equal Rights Amendment. NOW was able to bring about changes large and small — to hiring policies, to credit-granting rules, to laws — that improved the lives of American women.”

NOW was a groundbreaking organization. So when Friedan moved to purge lesbians from the organization in 1970 — after calling lesbians the “lavender menace” in an interview with the New York Times magazine — it was significant on a myriad of levels.

That purge effectively separated lesbians from mainstream feminism, just as they had been separated by gender from the decidedly male gay liberation movement.

NOW’s Susan Brownmiller, whose book Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape would become another critically important feminist treatise, tried to make a joke of Friedan’s comment, calling it a “lavender herring.” But that just further alienated lesbians in the organization.

Mainstream media had already dismissed the feminist movement as “a bunch of bra-burning lesbians,” so Friedan and other straight feminist leaders were acutely sensitive to this labeling — and dismissal — of all feminists as lesbians. Friedan wanted “feminine feminists” in the movement; she and many others did not want feminism “tainted” by “man hating” and lesbianism.

As lesbian activist Karla Jay later wrote in her memoir, Tales of the Lavender Menace: A Memoir of Liberation, “I’m tired of being in the closet because of the women’s movement.”

The blatant hostility toward lesbians and Friedan’s warnings about the “lavendar menace” took on their own activism. NOW established policies exclusionary of lesbians in the early years of the organization. As NOW newsletter editor Rita Mae Brown said, “lesbianism is the one word which gives the New York NOW Executive Committee a collective heart attack.”

The lesbian purge at NOW had a ripple effect for lesbian activists. It was surprising — even ironic — considering that lesbians had been so pivotal in founding NOW and in the impact and influence of second wave feminism. Many of the key figures of that wave of feminism and of NOW itself were lesbians, including NOW co-founder Pauli Murray; Rita Mae Brown, member of The Furies collective and author of the first mainstream lesbian novel, Rubyfruit Jungle and editor of the NOW newsletter; and graphic designer Ivy Bottini, who designed the NOW logo still used today and was president of the largest chapter of the organization, New York NOW.

And yet, Friedan and other straight feminists, including Shirley Chisholm and Gloria Steinem, still felt that the “lavendar menace” was problematic for the movement. Lesbians were seen as “man haters,” and mainstream feminism was intent on presenting the movement as pro-woman, not anti-male.

In addition, lesbians were still seen as perverts and even as mentally ill. It would be several more years before the psychiatric community’s DSM would change its view that homosexuality was a mental disease.

As Hannah Quayle wrote in a blog post about the purge, “Lesbians were placed within an unnatural category of the ‘third sex.’ This ‘third sex’ was associated as a gross abnormality which violated female anatomy, heterosexual desire and gender behavior by associating masculine features upon the female body. In this sense, lesbians were not considered ‘real women,’ and stood outside the category of ‘woman’ in a physical, sexual, personal and political sense.”

Quayle asserted that within the mainstream feminist movement and NOW, “Lesbians had to find an effective way to address the accusation that their masculinity was somehow complicit with men and the patriarchy, and that lesbian influence would not in fact dismantle strict heterosexual categories as it was widely believed. Heterosexual feminists excluded lesbians from the feminist movement in the 1960s based on this discomfort towards their sexuality.”

In 1969, the year of the Stonewall riots, New York NOW chapter president Bottini broached the subject of lesbianism and the movement in a public forum titled “Is Lesbianism a Feminist Issue?” Bottini — like Brown, Murray and others — thought lesbians were leaders of the feminist movement, not background players. After all, it was lesbians like Susan B. Anthony who had also led the first wave of feminism in the U.S.

But Friedan was adamant that lesbians could not be allowed to derail the feminist movement and the work that she and others were doing to establish equity in employment and reproductive rights (Friedan was also co-founder of NARAL).

Lesbian visibility, Friedan believed, would allow men to dismiss the feminist movement as fringe and something most women didn’t want to be associated with. Trumpeting her assertions and coining the term “lavender menace” — which a group of New York lesbians would later adopt to form a group of radical activists — Friedan, NOW’s national president, fired Brown from her job as newsletter editor, then orchestrated the purge of lesbians, including Bottini, from NOW’s New York chapter.

The action did not go unnoticed. At the 1970 Congress to Unite Women with 400 feminists from NOW and elsewhere in attendance, Brown, Bottini, Karla Jay and a dozen other lesbian feminists marched to the front of the auditorium wearing T-shirts that read “Lavender Menace.”

One of the women, Charlotte Bunch, who was also a member of The Furies collective with Brown, read the Lavender Menace’s manifesto, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” considered the first major lesbian feminist statement. That action was among the first to challenge the heterosexism of straight feminists and present lesbians not as a “menace” or mentally ill perverts, but rather as being more feminist than anyone, because they were women independent of The “woman-identified woman” defined herself without reference to male-dominated societal structures and “gained her sense of identity not from the men she related to, but from her internal sense of self and from ideals of nurturing, community and cooperation that she defined as female.”

Later Bunch would write, “It is the primacy of women relating to women, of women creating a new consciousness of and with each other, which is at the heart of women’s liberation, and the basis for the cultural revolution,” articulating what would become a cornerstone of lesbian activism in the 1970s in the post-purge feminist movement.

Friedan’s efforts to suppress lesbians in the movement instead caused pushback from within NOW’s ranks that resulted in a near-embrace of lesbians within NOW just two years post-purge. In 1971, NOW passed a resolution declaring “that a woman’s right to her own person includes the right to define and express her own sexuality and to choose her own lifestyle [sic].” Another conference resolution declared it was “unjust” to force lesbians mothers to remain in heterosexual marriages or remain closeted to keep custody of their children.

The NOW Task Force on Sexuality and Lesbianism was established in 1973 and NOW resolved to introduce and support civil rights legislation designed to end discrimination based on sexual orientation. Del Martin was the first open lesbian elected to NOW, and Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon were the first lesbian couple to join NOW. Martin and Lyon were co-founders of Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian civil rights organization in the U.S.

Over the next 20 years, NOW would go on to support fights for everything from custody battles to same-sex marriage and lesbians in the military. NOW also supported hate crimes legislation that included lesbians and trans women as early as 2002 and came out in support of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr.

Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expands the 1969 federal hate crimes law to include sexual orientation, gender, gender identity and disability.

And it all started with a purge that made history and redefined the feminist movement.