Damien Echols has captivating audiences as the star of four motion pictures, but he’s not someone you’d call a Hollywood insider. In fact, he’s rarely even seen himself on screen.

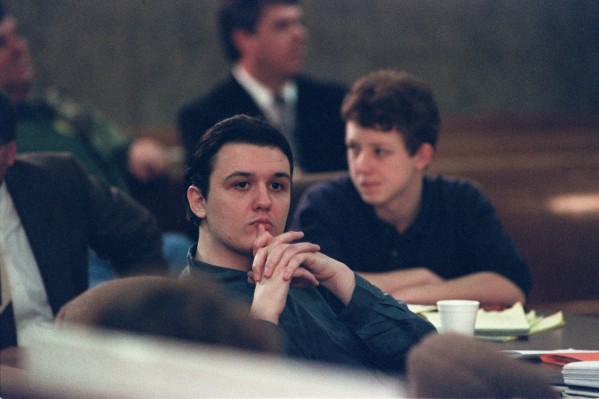

Echols came to his fame the hard way: As an unjustly accused murderer who became the subject of three documentaries — Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996), Paradise Lost 2: Revelations (2002) and Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory, which was nominated for a best documentary Oscar last year.

In each of those films — made over the course of the nearly 20 years that Echols, and two other young men sentenced for their crimes, spent in prison trying to prove their innocence — audiences could agree on one thing: Like them or not, Echols and Company were railroaded by narrow-minded and corrupt prosecutors, judges and investigators who branded them as sex perverts and devil worshippers who sexually molested and murdered several boys in West Memphis, Ark., in the early 1990s. They were accused of all kinds of occult motives (the charges read like something from the Salem Witch Trials), even though there was precious little evidence against them. Indeed, it was their outsider status that seemed to doom them.

“The problem was perception — everyone knew from the beginning we didn’t do this, but they didn’t care, so they railroaded three white trash kids,” Echols said. “We were easy targets.”

Now, though, Echols tells the whole story from his own perspective. West of Memphis, which opens Friday at the Angelika Mockingbird Station Film Center, is the two-and-a-half hour summation of Echols’ incomparable ordeal, from death row to freedom. And it all became possible because of some unlikely champions: Filmmakers Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, best know for the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit movies.

“At the time we started making [West of Memphis], Paradise Lost 3 hadn’t been released,” he said over coffee at the Crescent Court Hotel during a publicity tour last month. “When we started on it, no one was even looking at the events anymore.”

That’s where Jackson and Walsh proved instrumental.

That’s where Jackson and Walsh proved instrumental.

“Peter and Fran were huge on this case. While they were making King Kong and The Lovely Bones, they were calling [authorities] on our behalf,” he says. “This was years before we started [filming] on the documentary. We started working on the way the public [perceived us]. Peter and Fran became the heads of our legal team. Peter is the smartest human being I’ve ever seen in my life. He sees life as a chess game.”

Making West of Memphis became a mission to get the story told right.

“We wanted to go in a different direction that the Paradise Lost movies. That group was not investigative journalists. Our director [Amy Berg] was. One of the things that kind of amazed me was, in the past, the judge and prosecutor would not talk to anyone. [Berg] was amazing [at getting them to talk on camera]. What you’re watching [when you see West of Memphis] is the case we would have made in court,” Echols says.

Even though he was the subject of three films, he didn’t see any of them until fairly recently — and that under adverse conditions.

“I never saw them — I did see the third film within a month of getting out of prison, but I was in such a deep state of trauma I could not process it in any normal way — it felt like living through it all over again,” he says.

Indeed, making this movie — Echols and his wife are producers on it — has been a chore he’d rather not endure. Even the press tour has weighed on him, constantly reliving horrendous events from his life.

Echols was arrested in June 1993, and was first set to die in the state’s death chamber on May 4, 1994; it wasn’t until 2011 — virtually half his life — that he was finally freed. But in many ways he’s still not free.

“We’ve been on the road two-and-a-half months now. I hate talking about this case over and over. We’re doing this only so that the person who did kill those boys will be held accountable. It’s not over; we will still be fighting.”

West of Memphis opens today at the Angelika Mockingbird Station.