‘Show Boat,’ ‘Big Meal,’ ‘Empress’ movingly portray the full landscape of life

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

Theater is a matter of life and death in North Texas this month — literally.

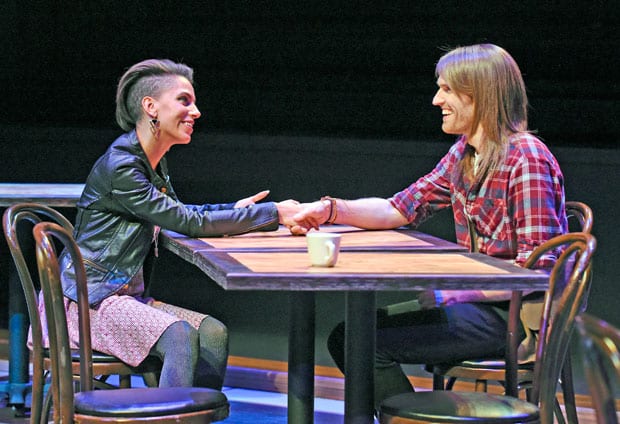

At WaterTower Theatre, the entire life-cycle is at issue in The Big Meal, a tender, funny, painfully real portrait of a family from courtship to death. It starts with two 20somethings Nicki and Sam (Kia Boyer and Garret Storms), meeting for an awkward first date or two, usually over dinner and drinks. With the chime of a bell, it’s now at least a decade later, with Nicki and Sam now played by Sherry Hopkins and Jakie Cabe. They reignite their relationship, and to the surprise of both, agree to marry … just so long as they don’t have children. A chime later, and two rug-rats (Kennedy Waterman and Alex Duva) come running in — apparently the call of biology was too much to resist.

At WaterTower Theatre, the entire life-cycle is at issue in The Big Meal, a tender, funny, painfully real portrait of a family from courtship to death. It starts with two 20somethings Nicki and Sam (Kia Boyer and Garret Storms), meeting for an awkward first date or two, usually over dinner and drinks. With the chime of a bell, it’s now at least a decade later, with Nicki and Sam now played by Sherry Hopkins and Jakie Cabe. They reignite their relationship, and to the surprise of both, agree to marry … just so long as they don’t have children. A chime later, and two rug-rats (Kennedy Waterman and Alex Duva) come running in — apparently the call of biology was too much to resist.

The play continues on that way, with abrupt changes of setting and time … as well as cast. At first, John S. Davies and Lois Sonnier Hart play Sam’s parents; by they end, they are portraying Sam and Nicki themselves, now great-grandparents of pairs of kids (Cabe and Hopkins), grandkids (Storms and Boyer), etc.

Sound confusing? It’s really not, though it does demand your attention, something you willing give over as you become inextricably rapt by the authenticity of the lives of this family, which include dating, divorce, infidelity, cancer and of course death — the “big meal” in playwright Dan LeFranc’s construct. Each time the stage manager steps onstage with a full plate of food and a napkin-wrap of silverware, it’s someone’s turn to eat … and walk off-stage forever. Dinner becomes a form of Russian roulette.

Initially, the speed of the transitions, and the unmiked voices, force you to strain a bit to catch everything. And then you realize that director Emily Scott Banks is doing that intentionally, making you lean forward and engage. It’s a crafty way to rope you in, and for 100 uninterrupted minutes, she makes you laugh and breaks your heart. By the end, with Sam quaking from Parkinson’s, his mind fading as Nicki feeds him one last time, you’re wrecked. (Damn her montage of couples — gay and straight — and exquisite use of music to pluck at our emotions!)

The cast ably serves Banks’ vision. Storms is a protean actor who, better than anyone on North Texas stages right now, fluidly transforms from one type to another (a scene where he portrays every boyfriend Boyer’s character ever brought home is a subtle tour-de-force). Waterman — barely a teen — wowed audiences in Harbor and Daffodil Girls, and cements her rep as a “kid” actor with mature talent. Of all local theater companies, WaterTower seems the one most consistently occupied with telling the human experience with kitchen-sink verisimilitude. The Big Meal adds to that catalogue, a kind of modern-day Our Town. Come prepared to cry.

Kia Boyer and Garret Storms, above, begin a romance that becomes an entire lifetime in WTT’s ‘Big Meal.’ (Photo by Karen Almond)

You might well cry throughout Show Boat, too — the final production of the Dallas Opera’s current season and the first time the company has produced an American-style musical, not a traditional opera (though it’s actually more of an operetta). The songs — “Ol’ Man River,” “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” “Bill” — are firmly ensconced as charter entrants in the Great American Songbook, and as delivered here, wrenching arias as well-honed as Mozart’s “Porgi amor” or Offenbach’s “Barcarolle.” Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II may not have reputations as “opera composers,” but their work stands with some of the greats.

It helps that the Dallas Opera has assembled a cast that not only sings with the strength of opera, but can act up a storm.

The story revolves around Magnolia Hawks (soprano Andriana Chuchman), a young girl touring with her parents about the Cotton Blossom, a moving river boat that wanders the Mississippi at the turn of the last century, performing overwrought melodramas for residents of the port towns. She meets the gambler Gaylord Ravenal (baritone Michael Todd Simpson), a tall and impressive dandy who sweeps her off her feet, giving her and their daughter a good life until his losses pile up, and Magnolia is forced to work for a living, becoming a celebrated singer.

Chuchman and Simpson have real chemistry, which you feel during their duet “Make Believe.” But it’s soprano Alyson Cambridge as the tragic Miss Julie LaVerne, a half-black actress “passing” for white in the segregated south, who delivers the show’s major knockout punch. “Bill” sounds like a novelty song — a sweet, goofy ballad about a woman infatuated by her seemingly average boyfriend — but Cambridge turns it in a breathtaking torch song of an alcoholic has-been, giving her all at the end of her career. And basso-profundo Morris Robinson brings it for his (and the show’s) signature song, “Ol’ Man River.”

As is often the case, the comic role of Cap’n Andy is a scene-stealer, and the limber dancer Lara Teeter commits grand theft. It’s a joyously upbeat performance in a show filled with as many dour moments as colorful bustles — the prototype for the modern musical, conducted with brio by Emmanuel Villaume.

Music is essential to another downbeat story about life and death. It’s Oct. 4, 1970, and Janis Joplin (Marisa Diotalevi) is drowning her sorrows in an L.A. hotel room when her idol — the late blues great Bessie Smith (M. Denise Lee) — seems to step out of the album she’s listening to and enters Janis’ world. Janis has died of a drug overdose and is just beginning to realize it; Bessie apparently is there to ease her transition into the afterlife.

The meeting of these musical greats, both cut down at the peak of their skills (Joplin at age 27, Smith at 43), forms the crux of Dianne Tucker’s reverie on American Music The Empress and the Pearl, now at Theatre 3’s downstairs space. Through songs (mostly Smith’s), conversation and some theatrical exposition, Tucker delineates the similarities between the performers, but also their differences as people and artists.

It’s not a balanced portrait. Joplin comes off as the more ungrateful and self-destructive of the two, a self-indulgent narcissist who ruined her raspy voice by burning out her soulfulness too recklessly, as well as ill-conceived romances with men and women. That’s something she shared with Smith, a sexually voracious singer who truly lived the blues.

Neither Lee nor Diotalevi look or sound much like their avatars, but it hardly matters; Lee in particular has the rich vocal chops to turn the small underground space into a Depression-era speakeasy. You can practically smell the gin in this cabaret.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 22, 2016.