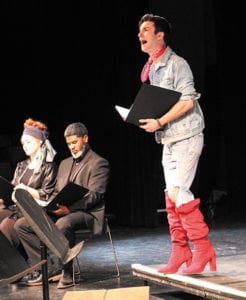

After Terry Loftis, standing, read ‘Living Over the Rainbow,’ he reached out to author Roz Esposito, seated, about getting the musical ready for Broadway. (Photo by Arnold Wayne Jones)

How a musical about the murder of a gay teen gained momentum in Dallas

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

It is a warm spring evening deep inside the sweaty halls of the Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, and about 50 people have flashed back to their teen years to find a seat in the black box theater. Most of them are theaterfolk — actors, singers, directors, producers — specially invited by one of their own, Terry Loftis, for an exclusive event.

The lights dim and a young boy runs onto the stage to happily don a pair of kinky boots and sashay around prodigiously, flamboyantly gay. He flirts and flits for a few moments, and is then gunned down in the back of the head by a classmate. A pop gospel song plays. And the rest of the story begins.

It will repeat itself the following night.

These audiences are getting an early look at a brand-new musical inspired by the actual, horrific murder of Larry King, a gay (possibly trans) teen in California in 2008 called Living Over the Rainbow, conceived of, written and composed by a cisgender lesbian life coach named Roz Esposito with no prior experience as a composer or librettist for musical theater.

It’s all so unlikely that this pairing of circumstances would lead this far down the line. But unlikely things happen all the time in show business.

I started college as a theater actor, and I was with the Groundlings so I’d written sketches and developed characters. I’ve written songs, but never a musical or a play,” Espositio says. So yeah — totally new to her, especially at the level it has gotten to now.

But it’s not as if she had a choice — at least in her mind.

“In 2008, I picked up the paper and saw a picture of Larry, and it just jumped off the page at me. I was completely taken with him.” Initially, she and a friend made a short documentary film about the killing. But that wasn’t enough.

“I’m very spiritual. I kept thinking ‘What does the soul have to do to move on?’ This [story] was touching on everything that was important to me: LGBT, human rights, forgiveness, spirituality. The universe tapped me on the shoulder and said ‘This is a musical.’”

Theater — good theater — doesn’t just happen. Sure, you can throw on a cape, stand on a stage in your backyard and invite your friends over to watch you improvise, but the world of professional musicals is far more complicated. It starts, of course, with an idea, a script, a score. Then someone with money needs to show an interest. There are rewrites and suggestions and feedback. But it’s all still just words and notes on a page until someone ponies up some cash to get actors to bring life to the characters, musicians to play those notes, a director to work out the mechanics and ultimately an audience to absorb it.

What’s taking place at Booker T. those nights in April is one of the necessary steps in that process called “mounting a workshop.” This seemingly impromptu guerilla production actually cost thousands of dollars to put up and employed dozens of experienced professionals to make happen, even for just two nights in front of non-paying customers.

It’s common in professional theater, but perhaps less expected on this scale done independently in Dallas. That is, until we had our own Tony-nominated Broadway producer in town to get the job done.

Loftis came by his producer title unexpectedly. Barely four years ago, he was just a man with a passion for the arts. A singer and patron of live performances, he had raised money for causes for much of his adult life. But when he was asked by a friend to put together investors for the new Kander and Ebb musical headed for Broadway, he agreed … despite his lack of experience as a New York theater producer. His efforts landed him a co-producer credit on The Visit with Chita Rivera and Roger Rees; within a few months, when the list of Tony nominees for best musical was announced, Loftis’ name was read out. (The Visit lost to the team from Fun Home.)

Rather than being a one-off experience, Loftis was smitten with the process. Two years later, he was back on Broadway with the original musical Bandstand; now, he’s an outright impresario, serving as vice president of investor development for the Broadway Strategic Return Fund, which has had a hand in lining up investors for Broadway productions like The Cher Show, Pretty Woman The Musical and Hadestown — big, splashy tentpoles all.

But Loftis maintains a personal interest in smaller, more intimate works as well. Which is what drew him initially to Living Over the Rainbow. (He’s working on this independent from his day job as the interim lead producer.)

He happened upon the script in a way that almost seems like a Hollywood cliche.

“I got the book through Mel England, an actor in L.A. and New York who knew Roz. I was staying with [Mel] in New York, and he slipped [the script] into my bag,” Loftis says. He discovered it in the airport. “I read it on the flight back to Dallas, and before I had listened to any of the demos of the score, the story kind of shook me. I could relate to that character — I went through the verbal and physical bullying. [Reading it brought] this huge influx of emotions and identity and not having anyone to talk to. That whole connection of me being gay in an all-black neighborhood where everything I had experienced in middle school would escalate. But I had a shitty time in school — this poor kid lost his life for just being who he was.”

It took a few months before Loftis and Esposito could meet in person, but when they did, the connection was made.

“We immediately bonded and fell in love with each other,” Loftis says of Esposito, a wild-maned redhead. Loftis gave her his notes about the script and the score; they decided amongst themselves that it would be important for the director to be gay or lesbian or have some personal familiarity with queer subject matter. Loftis reached out to friends and mentors in the New York theater scene.

All of this “takes place really quick — they will say ‘I’ve got four people you have to talk to about this,’ and you call them,” he says. He selected a music director; he began to assemble a cast, especially the leading role.

This was in early 2017; by the summer of 2018, Loftis had signed Uptown Players as a co-sponsors of the project.

“We looked at the script, and it fit our mission really well,” says Craig Lynch, who with Jeff Rane founded Uptown Players. “For me it was the message of bullying and forgiveness [that resonated]. And Roz’s music was also snazzy and catchy. It was something we decided we could invest in and get on the ground with [a New York-bound] production.” They helped finance a basic reading in July of 2018 in Irvine, Calif. After that is when the real work began.

It took Esposito a long time to get there. She speaks in the free-spirited, bohemian style of a flower child. She doesn’t write her music, she downloads it, as if tapping into the energy of the cosmos. From the initial idea in 2008, it took her until about 2015 before she was willing to show her work, even to friends.

“The first reading I ever did was with about 15 invited people in a friend’s living room,” she recalls. “Ten minutes into it, I wanted to slit my wrists. Then a few years later, when more music was written, we did it in front of about 30 people, and it was beginning to fit into place. People were over the moon about it.”

That’s around the time her friend Mel England mentioned he had connections in New York theater and would be willing to slip a copy to his friend Terry Loftis.

Nine months after the first reading, Loftis has raised money from investors to help finance the Dallas workshop (even so, he self-financed about two-thirds of the expenses). The original director was dropped, and seven days before that first performance, Loftis brought in Terry Martin, former artistic director of WaterTower Theatre, to take over. And even in front of small, invited audiences, the tension is high.

“The show goes up, and it’s outside you,” Esposito says. “We had two weeks [to get the workshop mounted] — we’d work on the script during the day and with the actors at night. There was a stage manager — a real stage manager! This is what a production Off-Broadway is like.”

“Opening night of a workshop, it is probably 60 percent butterflies in anticipation and 40 percent ‘holy shit, what the hell am I doing?’” Loftis says. “As a producer, you have to buy into the vision of this hippie first-time playwright and she has to buy into me as someone who, despite New York experience, has never produced something from its infancy. Fear comes into it — in fact, the fear aspect is the same as opening night of a Broadway show. Until you’re actually watching the audience, seeing if they are clicking with the beats of the story, it’s a nightmare.”

The first night was a success; the second made Loftis more nervous.

“The audiences were completely different,” he recalls. “The first night, the cast was in synch as was the audience, but the second night, while the audience was bigger, there were some moments that didn’t happen. I think we didn’t pull off two specific scenes. Even so, the feedback was incredible … and incredibly valuable.”

The next day, Loftis held a conference call with the principals (Espositio, Martin, the music director, Jeff Rane from Uptown Players) and “we ripped it apart, scene by scene, and collectively made recommendations about changes.” Was it content or the actors performing it that wasn’t working? What was best? Worst? “That’s a grueling, painful process. There were changes to the book, some to the score — for example, we felt the angels had too much going on musically, so we turned the focus to Larry and [his tormentor] Brian and cut two of the angels’ songs. The next version will have a lot more emphasis on the background of the main characters: how did Brian get to be violent, how did Larry get kicked out of his home for coming out?”

Dylan Mulvaney plays the murdered teen in the workshop mounted in Dallas this spring. (Photo by Arnold Wayne Jones)

“I’ve been through it, man — I’ve been rejected [in my career], but I’m resilient,” says Esposito. “You sit at the computer in your skivvies [for years writing away], and you get it to the point where you present it to an audience, and then at the debrief [you hear it all]. But I saw what needed to be done. You never knew how to do it, but it gets done — you’re gonna ask the universe to download it for you.”

She’s a collaborative person by nature, but it all rests on her shoulders — she’s the author, composer and lyricist. And she knows what she likes.

“My whole thing about musicals that I love is that they have stand-alone songs. I come from the pop-song world and am always thinking about ‘What I Did for Love,’ ‘Memory.’ But I had to learn how to write different kinds of songs — I know what they are having listened to musical theater, but I’ve never had to write them. My musical director has been amazingly instrumental in [guiding me].”

She agreed that Larry needed more background. She remembered that he was abandoned by his mother at an early age, so she wrote a song called “Mama.” She added another song. She continues to tweak it almost every day.

“When I sit down, I think, ‘We need more detail, and we need it up front’ and I find the spot, and I start writing into the script — the scene and the dialogue and the lyric. And sing the music into a [recorder]. Then I sit at the piano and plunk it out.”

The next phase will be doing either a full showcase run in a regional theater outside of Dallas — Los Angeles or perhaps even New York — or doing a concert version with a paid audience (and critics allowed) which is also when Loftis will invite other producers to gauge their interest.

“We could probably do a showcase within the next year and then based on any more work that has to be done, getting to Off-Broadway could happen very quickly. If this goes as well as I anticipate, all things being great, I would see it on Broadway in 2022 or 2023.”

Esposito is all over that plan. But she has other ideas as well.

“Of course I’d love to see it be a big smash on Broadway and to make a ton of money from my art,” she says. “But my vision is that the show needs to be done in high schools all over the country, because that’s where it needs to be seen and heard. We have this disease of The Other — there’s somebody other than you [that’s bad]. Homophobia is just a disease of that [mindset]. I want Living Over the Rainbow to be a platform to go around and speak about this story. That’s what’s important.” █

Amazing my dear friend Terry is achieving his his dreams❤️ Perseverance really does work