Pyeatt and Deaton in ‘Grand Hotel’

Maybe you can blame the rain, but opening night at Lyric Stage‘s production of Grand Hotel was not a sellout, and that’s a shame. For some years now, Lyric has been doing the kind of musicals no one does anymore outside the opera world: Large-scale, huge cast, full-orchestra full-on revivals of classics of the Golden Age of B’way and beyond. It’s easy to get folks excited about Rodgers & Hammerstein and Sondheim; it’s a harder sell, apparently, to let them know just how good a forgotten hit like Grand Hotel is (in ran from 1989–1992, and won Tommy Tune one of his gazillion Tony Awards).

The upside is, you should be able to score some good seats to the final performances of the show, being given a glorious production in Carpenter Hall. The score, largely rewritten by the great Maury Yeston prior to its original opening, is a lush and extravagant old-school collection of waltzes and jazz and assorted genres that all come together in a sung-through presentation. When Christopher J. Deaton — playing the beleaguered, cash-strapped, but endlessly charming Baron — hits the final note on the ballad “Love Can’t Happen,” you’re convinced we are living in our own Golden Age of musicals … and its center is Irving, Texas.

Grand Hotel is a portmanteau of stories, all intertwining in the lobbies and suites of a Berlin luxury hotel in the interbellum just before the Great Depression. A beset bellhop (Anthony Fortino) must choose between career and family (and the unwanted advances of his supervisor); a 50-ish ballerina (Mary-Margaret Pyeatt) struggles with self-doubt while her devoted, closeted assistant confidante (Jacie Hood Wencel) pines unrequited; a dying bookkeeper (Andy Baldwin, who lets loose in a heart-breaking turn) finds new meaning when he meets an conniving secretary (Taylor Quick) intent on becoming a star; and on and on. Fully 28 actors appear with three dozen musicians, hoofing and huffing for two-and-a-half hours. This truly is a grand Hotel.

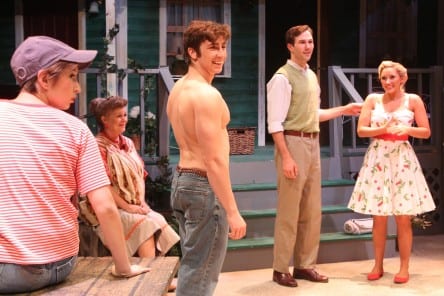

Maya Pearson, Stephanie Dunnam, Haulston Mann, John Ruesegger and Grace Montie in ‘Picnic’ (Photo by Linda Harrison)

Over at Theatre 3, things are getting steamy with William Inge’s satire of sexual hypocrisy, Picnic. Inge was a closeted gay man who explored the realities of sex in the 1950s in a way no one other than Tennessee Williams was attempting, but unlike Williams’ Southern Gothic excesses, Inge imbued his stories with a Midwestern sensibility. Blanche DuBois was unstable; schoolmarm Rosemary is simply horny and desperate.

People were horny before the sexual revolution, something that made Inge’s plays a decade earlier seem quaint; he fell out of favor in the 1960s, after winning an Oscar for Splendor in the Grass, one of the most frank depictions of teenaged puppy love put onscreen.

Sex oozes from Picnic, especially in the persona of Hal Carter, played by Haulston Mann. Mann (aptly named) is a muscular, cocky sort, who doesn’t walk on the stage so much as he struts across it. His drool-worthy physique sets the women of this small Kansas town aflutter with desire, from high-school tomboy Millie (Maya Pearson) to randy ol’ gal Mrs. Potts (Georgia Clinton) and the aforementioned Rosemary, played to tragicomic perfection by Amber Devlin. Rosemary pretends to be happily spinstered, renting a room in the house of the widowed Mrs. Owens (Stephanie Dunnam), but secretly craves a man, even if it’s perpetual bachelor Howard (David Benn, who looks like Mitt Romney but who gets a whole lot more sympathy).

Hal’s appearance primarily screws up the budding romance between Millie’s sister Madge (Grace Montie) and her beau, town rich-kid Alan (John Ruegsegger), an old fraternity brother of Hal. Hal “ruins” Madge, but also sets her free. That’s the irony of sex in the 1950s: Folks were starting to realize it wasn’t shameful, but liberating.

Picnic can feel clunky at times (the bromance between Hal and Alan reeks of awkward homoeroticism, and their discussions feel forced), but it can be unexpectedly funny (Inge himself called it a romantic comedy), but the cast at work here — especially Devlin, Ruegsegger and often Mann — makes it endlessly watchable. It’s enjoyable to rediscover a nearly-forgotten classic of midcentury theater.