We are in the era of post-modern theater, like it or not. And I don’t always like it.

We are in the era of post-modern theater, like it or not. And I don’t always like it.

Theater is a dynamic art form, and three cheers for experimentation and finding the “new normal.” But for about the last decade, plays have relished a little too much in reminding us that they are plays, while trying to turn a “night at the theater” into a sensory overload. Projected sets. Ear-splitting musical cues that occur suddenly. Lighting designs that approximate film editing more than staged-scene transitions. Sometimes, some combination of these work (American Idiot, The Lieutenant of Inishman, Chinglish); sometimes they don’t (Dirty Dancing springs horribly to mind).

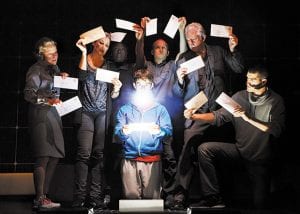

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, now at the Winspear Opera House, falls generally into the “plus” column of these po-mo plays, though it feels more sizzle than steak. Based on Mark Haddon’s book (for years, the biggest-selling book in British history), it tells the story of 15-year-old suburban kid Christopher. Christopher is “special needs” — the word “autism” is never used, though it’s clear he falls on the spectrum of savants with underdeveloped social skills. Christopher hates to be touched (even by his parents), he cannot tell a lie (though he proves himself adept and selective truth-sharing), he’s good at math but not at metaphor (he’s able to sit for his “A levels” — roughly the equivalent of SATs in the U.S. — two years early, but doesn’t understand when people say “I’ve got my eye on you” or “you’re the apple of my eye”). His manias conspire when he discovers the brutally murdered dog of a neighbor, and determines to figure out who committed the crime. (The reveal is not at all surprising.) This leads him, in Act 2, to run away to London in search of a different set of answers.

The novel, which is told from Christopher’s perspective, is an “unreliable narrator” book, a chance to see the world through the unique eyes of its complex protagonist. The play can’t do that exactly, so Christopher’s story — in the form of his journal — is read aloud by his teacher (with repeated references to the fact we are actually watching a play about that story); we get inside Christopher’s head by the use of sound, movement and lighting effects that turn the electrified cube that is the set into a puzzle box. It’s as loud and weird to us as the world must seem to Christopher.

The novel, which is told from Christopher’s perspective, is an “unreliable narrator” book, a chance to see the world through the unique eyes of its complex protagonist. The play can’t do that exactly, so Christopher’s story — in the form of his journal — is read aloud by his teacher (with repeated references to the fact we are actually watching a play about that story); we get inside Christopher’s head by the use of sound, movement and lighting effects that turn the electrified cube that is the set into a puzzle box. It’s as loud and weird to us as the world must seem to Christopher.

That works effectively… for about half the 150-minute performance time. When Christopher is set loose in London — navigating the tubes, wandering the streets, encountering strangers — it turns into an almost psychedelic nightmare that makes its point long before the adventure ends.

It’s that awkward admixture — Act 2 begins with a nerve-shattering drum beat, without so much as the lights dimming to warn you to put away your cell phone — that makes Curious a slight conundrum: You appreciate it more than you enjoy it.

The same was true, to be frank, with director Marianne Elliott’s last stateside production, War Horse. (Curious is the longest-running new play on Broadway to open since 2000; War Horse is No. 2.) War Horse used life-sized puppets to tell its prosaic story of a boy and his quadruped; Curious uses similar “wows” to tell its story of a boy and his pet rat. But for both, the equation adds up to less than the sum of its parts; the pacing drags, and the effects lose their punch eventually. (The same is true of the full-frontal male nudity in Naked Boys Singing.)

The same was true, to be frank, with director Marianne Elliott’s last stateside production, War Horse. (Curious is the longest-running new play on Broadway to open since 2000; War Horse is No. 2.) War Horse used life-sized puppets to tell its prosaic story of a boy and his quadruped; Curious uses similar “wows” to tell its story of a boy and his pet rat. But for both, the equation adds up to less than the sum of its parts; the pacing drags, and the effects lose their punch eventually. (The same is true of the full-frontal male nudity in Naked Boys Singing.)

Before the gimmicks overstay their welcome, however, you’re delighted and intrigued by the stagecraft, which employs Tony-nominated choreography to move Christopher around his environment, a protean stage of hidden doors and LED lights and primary colors that set and re-set the mood. But it all meanders eventually, until you’re not entirely sure what you’ve seen. On opening night, the audience jumped up in applause at the end, appropriately impressed by the energy and creativity. That is, the audience members still there — a fair amount of attrition occurred during intermission. Whether the defectors missed out on the full impact or got the point quickly and moved on it anyone’s guess.

At the Winspear Opera House through Jan. 22.