The advent of Black Harlem was no accident, as one exhibit in Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow, now on display at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, explain.

(David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

A new exhibit at DHHRM illustrates how SCOTUS can grant rights and take them away

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

A new exhibit at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum reminds us that before some of the really terrible recent Supreme Court decisions, there was a series of awful decisions through the second half of the 19th century.

And if history repeats itself, yes, our rights can be taken away.

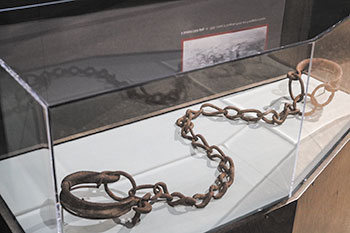

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow explores how Black Americans advocated for civil rights from the 1857 Dred Scott decision through the dawn of the 20th century. The new exhibit, created by the New York Historical Society, stands as a great companion to Rise Up, this spring’s history of the LGBTQ rights movement dating from Stonewall.

While that exhibit extolled the great strides we made in the Supreme Court over the past 20 years, the current exhibit explains how the court can just as easily trample our rights.

In Dred Scott, usually considered the worst decision ever made by the Supreme Court, the justices ruled that no Black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a U.S. citizen.

In Dred Scott, usually considered the worst decision ever made by the Supreme Court, the justices ruled that no Black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a U.S. citizen.

In 1866, the year after the end of the Civil War, the Republican Congress passed a civil rights law over Democratic President Andrew Johnson’s veto. The states also ratified the 14th Amendment. Both of these legalized citizenship for Black Americans.

The 13th Amendment, passed in 1865, abolished slavery. The 14th Amendment says, in part, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States … are citizens of the United States. … No State shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The same amendment created to protect the rights of former slaves was used in the three landmark LGBT rights cases — Lawrence, Windsor and Obergefell.

But, even though Dred Scott was overturned, that doesn’t mean the Supreme Court stopped issuing terrible decisions.

Homer Plessy, a Black man, volunteered to be arrested for sitting in a whites-only train car in Louisiana.

His white attorney, Albion Tourgee, argued that racial segregation of train cars violated the 14th Amendment.

The Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that public facilities that are separate but equal could remain segregated. Other cases followed that institutionalized “separate but equal” until the 1950s.

With these new Jim Crow decisions in place, the U.S. government abandoned the cause of Black equality. And new leaders created new organizations that demanded racial justice.

Even when Black soldiers fought in America’s wars, their patriotism wasn’t recognized. During World War II, African-Americans waged a “Double V” campaign for victory abroad and at home. Not until after the war did President Harry Truman desegregate the military.

The exhibit highlights the case of Sergeant Henry Johnson. On May 15, 1918, Johnson was standing guard on the battle field in the Argonne forest. He and another soldier were ambushed by about a dozen German soldiers. Although shot multiple times, Johnson wounded four enemy soldiers, forced other to retreat and saved another American from capture.

The story was recounted in newspapers across the U.S., and Johnson received the Croix de Guerre avec Palme, France’s highest military honor. In his own country, though, his valor wasn’t officially recognized until 2015 when President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Medal of Honor.

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow teaches that the Jim Crow Era didn’t end until passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. And recent Supreme Court rulings have chipped away at the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act.

The first program in conjunction with the exhibit is The Impact of the Harlem Renaissance in the Age of Jim Crow on Aug 9 at 7 p.m.

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow runs until Dec. 31 at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, 300 N. Houston St.