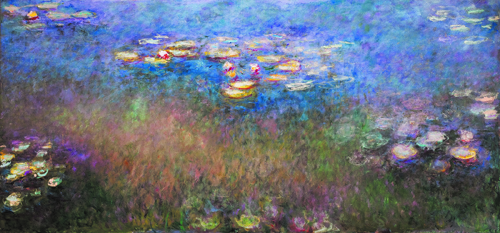

Water Lilies Agapanthus, above

A Japanese footbridge, irises, wisteria, water lilies and more are central subjects of Monet’s later works, on display now at The Kimbell

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

During his later years, Impressionist painter Claude Monet stayed close to home. And home was in Giverny, about 45 miles northwest of Paris, where he planted 247 acres of gardens and built a footbridge over a pond he filled with water lilies. Both footbridge and pond became central subjects in his later works.

The exhibit Monet: The Late Years at the Kimbell Art Museum through Sept. 15, concentrates on his work from 1914 until his death in 1926 at the age of 86. The exhibition bookends the artist’s career with Monet: The Early Years, organized by the museum several years ago.

Claude Monet (French, 1840 – 1926), The Japanese Footbridge, 1899, oil on canvas, Gift of Victoria Nebeker Coberly, in memory of her son John W. Mudd, and Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg 1992.9.1

The first room in the exhibit acts as a prologue. The Japanese Footbridge painted in 1899 is a subject Monet returns to paint many times during his later years at Giverny. A large water lily canvas displayed in the first room, dating from the early 1900s and painted in a style unlike the later work he’s best known for, highlights the pond and its plants that become an important focus of his painting a decade later.

Monet’s early works showcased his developing style, with works painted at a variety of locations as he traveled throughout France and elsewhere. To compare styles, walk from the Renzo Piano Pavilion, where the current exhibit hangs, to the museum’s Kahn building to see Monet’s La Pointe de la Heve at Low Tide from the Kimbell’s permanent collection. That 1865 painting was Monet’s first entry in the Paris Salon, and it launched the artist’s career.

Monet was the most successful painter in France at the time, which allowed him to buy his property in the 1880s. Working from his house allowed him to experiment with larger canvasses. Among his most famous works were a number of three-panel paintings, some taller than he was, which required help to move the canvas to his gardens and to paint the upper portions.

The Japanese Footbridge painting displayed in the first room is crisp and clean with well-defined patches of water lilies blooming beneath. The colors are bright, and the canvas is filled with light. Views of the bridge painted from the same perspective two decades later — hanging further on in the exhibit —are quite different.

The garden grew, and the bridge aged and became overgrown. Colors on Monet’s canvases changed to earthy tones, and the images became more abstract. Was this just an overgrown garden? Or as cataracts grew on the painter’s eyes, was this tangle of darker colors and bolder strokes simply what he saw?

Brushwork on some of his canvases became bolder during this later period in his life, but the style is also softer in some ways. Museum Deputy Director George Shackleford, who curated both Monet exhibits, described those bolder splashes of paint as expressionistic and the softer style as opalescent.

Monet may best be known for his water lilies, and they’re well represented in this exhibit of about 60 paintings, with 20 examples of the flower that filled his pond included. Several examples of earlier works hang in the first room. Then more than a dozen others hanging later in the exhibit show how his style evolved. Trees, sky and clouds reflect in the pond, but the lily pads are dominant on the canvas. At close range brush strokes are evident, but from across the gallery, the glorious colors merge into almost photographic images.

620328 Water Lilies (Agapanthus) c.1915-26 (oil on canvas) by Monet, Claude (1840-1926)

While Monet is best known for his water lilies, he was an iris fanatic and also planted wisteria, roses, day lilies and more. And a painting of irises in his garden is one of the most striking works in the exhibit.

In a series of paintings in the exhibit, Giverny’s willow trees, with their twisted trunks and branches, stand in for the artist as he aged. One of the four canvases is from the Kimbell’s own collection.

Finally, roses and wisteria are the subjects of a series of paintings featuring his house in the last room of the exhibition. The sun plays with colors as each canvas focuses on a similar landscape seen at different times of the day.

Large photographs of Monet’s studio complete that last room. At his death, many of the paintings in the exhibit were still hanging in his work area.

For any fan of Monet’s work, this exhibit is a treat. Many of the works are from private collections and others, from European and Asian museums, have rarely, if ever, been seen in North America. Once again, the Kimbell Art Museum proves what a treasure it is by presenting this first retrospective of the artist’s later years in more than two decades.

I’ve been looking forward to this show since seeing Monet: The Early Years, and it was as spectacular as expected. Just putting a bug in the ear of anyone at the Kimbell who will listen — Monet: The Middle Years. Just sayin.’

Monet: The Late Years continues at the Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth through Sept. 15. $18 adults. Discounts for children and seniors. Half price Tuesdays and after 5 p.m. On Friday. KimbellArt.org for tickets and more information.

My film Monet’s Palate is featured. Such a wonderful exhibit!

A toast to Monet.

Aileen Bordman