Amy and David Truong honor the memory of their son, Asher Brown, by working to get anti-bullying legislation passed

DAVID TAFFET | Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

Amy and David Truong joined about 350 people at the state Capitol in Austin on March 7 to talk to legislators about Asher’s Law. For the Truongs, passing the bill is personal. Asher Brown, who committed suicide in September after being bullied, was their son.

A number of people from around the state who had come to lobby thanked the Truongs for their support. Some shook hands. There were lots of hugs.

The couple shrugged off the thanks.

“We’re all in this together,” David told those he met.

Asher, 13, was a gay eighth-grader at Hamilton Middle School in the Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District in the northwest corner of Houston. He was, his parents say, a target of constant bullying.

On Sept. 23 last year, Asher went into his father’s closet, retrieved the 9-mm Beretta David kept there, and shot himself. David found his son’s body lying in the closet when he got home from work.

Since then, life for the Truongs has been tough, to say the least.

The Cy-Fair school district blames Asher’s death on problems at home and denied that the family had contacted the school about bullying, and the Truongs have been victims of “a constant stream of harassment” ever since, David said.

Every morning, David has to go out to pick up trash neighbors have dumped on the lawn and the beer bottles that have been thrown at the house.

Their house attracts gawkers and hecklers.

“People screaming and yelling from their windows as they drive by,” he said, and some rev their engines when passing the Truong house.

“Some even slow down, stare out their car windows and take several U-turns to gawk and stare at us if we are outside on the front lawn,” he said.

David rarely answers his phone anymore because most of the calls are harassing.

David took a few weeks off from work after Asher’s funeral but was having a hard time. Soon after returning, he was fired.

To avoid harassment in the neighborhood and school, they sent their other son to live with relatives.

But the most telling sign of how Asher’s death has affected this couple is that every time David or Amy mention Asher’s name, their eyes fill with tears.

A group from Youth First Texas was at the Capitol lobbying for anti-bullying legislation the same day as the Truongs. When Amy heard some of the stories of those teens, some of whom also attempted suicide, her shoulders slumped. She looked helpless.

Asher

While the school district blamed Asher’s suicide on problems at home, his mother described a loving son.

“My son was a warm and wonderful child,” said Amy. “He was smart and funny. He loved all of his pets and animals in general. He was well read. By the people who knew him most and accepted him for who he was, he would be your best friend.”

But Asher was bullied in school for two years.

He complained about it the first week of school in August 2008.

“They picked on him for being the new kid, not dressed in Abercrombie & Fitch, having a big head and big ears, his lisp, his chosen religion of Buddhism and their perception of him being gay because of his gentle demeanor and his love of choir,” his father said.

Bullies made jokes about anal sex when Asher would bend over to tie his shoe or ran slower than the rest of the class in gym, his father said.

David told Asher to report the abuse to his teachers, coaches and the school administrators, which he did.

“Amy and I would follow up with phone calls, visits, emails and our own handwritten notes when he would come back to us saying it hadn’t stopped,” he said.

Some of Asher’s classmates told the Truongs that they documented the harassment and bullying they witnessed Asher endure. They filled out their own “incident reports.”

David said that at home they always reinforced that they loved him unconditionally. When Asher came out to them, they told him they loved him no matter what.

Every night the family ate dinner together and talked. Asher seemed relieved just to have the chance to talk about what happened and seemed satisfied with his parents’ attempts to notify the school, David said.

Despite their denial after Asher’s death that the Truongs had ever contacted the school, David said administrators sounded concerned when they got through to someone.

“They told us, ‘We know about what happened to Asher,’” he said.

They always got the same message — when and if the school bothered to respond to their calls, he said.

School administrators told them, “We will do everything to take care of it and we assure you, everything is going to be okay.”

“They did not offer any suggestions,” David said, “But did continue to praise our efforts in working with them to help Asher.”

One even told them, “I wish other parents were as involved as you two are!”

The day before Asher killed himself was particularly bad.

“We did not see bruises on him the day before he died, but his behavior was out of the ordinary in that he did not join us in the family room as he would usually do,” David said. “Instead he chose to read quietly and keep to himself.”

But David said that Asher told him he had a terrible day without going into detail.

According to Asher’s classmates and their parents, bullies tripped him and he fell down a flight of stairs. When he got up and had barely regained his balance, they tripped him again and he fell down a second flight.

None of the assailants were charged with assault or disciplined by the school.

After his death, the school claimed that Asher, his parents, classmates, teachers nor anyone else ever made any reports of him being harassed, taunted or tormented by bullies.

David called these callous attempts to cover up and said it added to their grief and heartache.

The morning he died, Amy said she told Asher she loved him and to have a good day before she left for work. He said, “I love you, too.”

“I went to work and my son was fine,” Amy said. “I came home and he was dead. No one should ever have to come home to police tape around their house. And my son shouldn’t feel like it was the only thing he had left to do.”

“He died because he couldn’t take it anymore,” David said. “People harassed, persecuted, bullied him and no one gave a damn.”

But as much as they talked at home, David said Asher never spoke about suicide.

The school district

The school district continues to deny any blame.

David called administrators banding together to deny any knowledge of the bullying part of the “good old boy network” in the area.

And this isn’t the first time Cy-Fair has been in the news for bullying.

In October 2009, Jayron Martin, 16, was chased and attacked by a group of classmates who wanted to “beat the gay out” of him.

A group of eight boys surrounded him while a ninth attacked him with a metal pipe and beat him with his fists. Jayron was left with a concussion and numerous cuts.

A neighbor with a shotgun scared the boys away. Had he not intervened, Jayron may have been killed.

Jayron said he told the principal, an assistant principal and his bus driver that a group planned to attack him after school.

Students and others claiming to be from the school blamed Jayron for the attack. A number of comments with a variety of different stories were left on the Dallas Voice website under the story of the attack.

In that case, the main attacker was the only one arrested in the incident. He was charged with assault. Because it was handled in juvenile court, the records are sealed.

The school district denied liability since the attack happened off school property, but because of the national publicity, the school district had to do something. So they fired the bus driver. They investigated one assistant principal but did not discipline him or any school administrative staff.

But no one has been disciplined relating to the bullying incidents and ignored reports regarding Asher’s death.

David said, “No one has spoken to us and no further press releases have come from the school since it was revealed by the Houston Chronicle that the district spokeswoman, Kelly Durham, was the wife of Asher’s seventh-grade assistant principal, Alan Durham.”

The future

This week, the Truongs were back in Austin to testify for Sen. Wendy Davis’ anti-bullying bill before Senate Education Committee.

On their earlier visit to Austin, Amy said, “Children shouldn’t have to be tolerating this on any level. My son didn’t deserve it. None of the other children who go through this deserve it. It’s not a right of passage. It’s not boys being boys. This has gone way beyond that and people need to realize it.”

Amy works as an executive assistant and uses her time off from work to lobby for anti-bullying legislation. While not looking for a job, David devotes his time to that same goal.

He said they’d like to move but home prices have taken a much steeper dive in Houston than they have in Dallas. Their house is worth $40,000 less than when they bought it and they cannot afford to move.

And, David said, the suicide makes it much less sellable. Real estate agents would rather not touch a house that was the scene of a shooting.

“Maybe we can rent it out,” he said.

David said they’ve gotten very little sustained support beyond the LGBT community, families of Asher’s friends and their “wonderful and supportive family.”

“We received cards, emails and flowers from all over the country during the first week of the tragedy,” he said, adding that the family appreciated every prayer and every bit of support.

Now, the Truongs are focused on putting their lives back together with counseling and therapy and on keeping Asher’s memory alive with their commitment to help other LGBT youth by passing Asher’s Law and other anti-bullying legislation.

Dennis Coleman, executive director of Equality Texas, said that legislators must hear from their constituents as anti-bullying bills work their way through committee and onto the House and Senate floors. He said a phone call to a representative and senator was a good way to remember Asher.

The Truongs have been working closely with Equality Texas on the pending legislation and understand that despite the publicity about the suicides last fall, passing anti-bullying laws is an uphill battle.

But David repeated several times, “Together we will move mountains.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 25, 2011.

I am a gay man that went to school in the Cy-Fair district , finished school 30 years ago and am very, very saddened as to what has happened to and what has been happening to the Truong family. I am not surprised that the school board, teachers and all involved deny accountability for their sons suicide. Saying that nothing was ever said to them is ridiculous. It makes me ashamed to admit that I did go to school there. That area of Houston is full of single minded, bigoted rednecks. I want to thank those in Houston that have been helping the family through this crisis, and wish them the best of luck in the future.

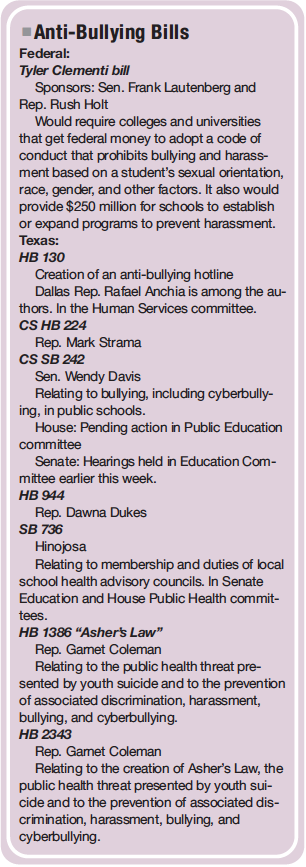

I am angered and disgusted at the school board and all those involved, without question something needs to be done. There needs to be a drastic, drastic change. A young boy’s lite is gone due to the IGNORANCE of others. That kind of ignorance is something that is taught and encouraged. A family has been changed forever. It amazes me that this still goes on in our country, in our own backyards. Seems to me its time for a new schoolboard. One with the interst of the students as their FIRST priority. My heart goes out to the Truongs, I can’t even begin to imagine the hurt they feel. I have no doubt that their son wouldn’t want them to stay in a place of hurt and pain. I also have no doubt that he’s proud of his parents for stepping forward and not staying in the shadows as others would have it. Thank you for posting the Anti-Bullying Bills. To the Truongs… Stay strong in this time of grief and may God Bless you and your family. I will be saying a prayer for all of you.

The people running the school district may not have the mental skill to do anything positive. Continuing to complain about them may never result in a change on their part. They may be bullied too.

The bullies and their parents are never noted by name in these articles. They seem to be protected and shielded. I’d like the Voice to identify the parents of the bullies, the harassing neighbors, the gawkers, the government authority and tell us the actions that are being taken to hold them accountable.

A new law will not produce any change unless it is enforced. The specific people who bully and allow their children to bully will continue until they are identified and legally stopped.