Gay teen Alex ‘Fitzy’ Fitzgerald talks about how bullies targeted him at an early age and how, despite bouts of cutting, drinking and drug use, he survived to find his place in the world

RENEE BAKER | Contributing Writer

renee@renee-baker.com

This is a story about a young man named “Fitzy” who was bullied at school for being unabashedly gay.

It is a story to remind us that while anti-gay bullying is not the only kind of bullying, and it is all wrong, anti-gay bullying can be worst kind because so often, LGBT teens have nowhere to turn for support, since even the people who are supposed to protect them — parents, teachers — can be as anti-gay as the bullies who torment them.

These are the type of stories that schoolteachers and administrators ought to listen to carefully and with an empathetic ear, acknowledging the physical and emotional abuse happening to the three out of four LGBT teens that skip school for safety.

They ought to acknowledge the right of LGBT teens to form gay-straight alliance support groups so gay youth are not dehumanized into a “they have it coming” category. And if they won’t do it because it is the right thing to do, then they ought to do it to avoid lawsuits that can be filed against them for not providing safety for their entire student body.

They ought to acknowledge the right of LGBT teens to form gay-straight alliance support groups so gay youth are not dehumanized into a “they have it coming” category. And if they won’t do it because it is the right thing to do, then they ought to do it to avoid lawsuits that can be filed against them for not providing safety for their entire student body.

Fitzy

Alex “Fitzy” Fitzgerald is a 16-year-old sophomore who suffered through elementary school in the Flower Mound and Lewisville school systems.

He said in neither school district did he feel safe, nor did his teachers or administrators get involved enough to protect him. And he feared for his life to the point of “checking out” because of it.

Fitzgerald is one of about two million U.S. school-aged youth the Human Rights Watch has estimated to be LGBTQ identified — with academic research solidly confirming 5 to 6 percent of youth are LGBTQ. Fitzgerald found himself struggling with both his gender and sexuality, and more so, severely struggling with those that said he got what he deserved when the bullies attacked him.

Fitzgerald is, unfortunately, not alone. A 2008 study released by Dr. Susan Swearer and her colleagues from University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Harvard Medical School found that adolescent boys bullied for being gay — or perceived as gay — were in a much different class of bullying than non-gay youth. In fact, they found that bullied gay youth experienced much greater psychological distress, greater verbal and physical bullying and more negative perceptions of their school experiences than boys.

Fitzgerald agrees. He said his path down “You’re So Gay” Lane began when he was only nine years old and wore a pink shirt to school.

“I didn’t know anything about being gay or straight then,” Fitzgerald said. “But my mom and sister encouraged me to wear what I wanted.”

Fitzgerald said he was too young to understand why the other kids thought he was so weird or why they called him “gay wad.” But when the fighting and bullying escalated to the point that his mom was regularly picking him up from school crying, he begged her not to send him back.

“The Lewisville fourth grade teachers could not have cared less for me,” Fitzgerald said.

Hoping for more support from school staff, his mother moved him to the Flower Mound school system in fifth grade.

Fitzgerald said things “started out okay” at Flower Mound, but kids in a clique soon began to pick up on his feminine, sensitive side, and the teasing and name-calling started again.

Instead of conforming, Fitzgerald began to stand up for himself, declaring his identity through a variety of clothing, from his “pink emo” girly phase towards a “darker and darker goth” style.

It took him awhile to try on a number of hats until one felt right, given what the environment would support.

Symptoms of being a target

Though he didn’t realize it, Fitzgerald said the bullying was really getting to him. He began seeing a psychiatrist to treat his depression, and by seventh grade, he had started “cutting” — three shallow cuts the first time, followed by cuts that went gradually deeper, the physical pain meant to mask the emotional.

“A girlfriend gave me my first razor blade,” Fitzgerald said, “and I cut regularly until the end of eighth grade.”

Fitzgerald said he cut nearly a hundred times out of sadness and anger. He said the pain inside would get so bad that he would just “go at it,” slicing up his arms, his ankles and his right thigh. He said he had “angry thoughts that couldn’t be expressed.”

His dad didn’t understand him, he said, and although his mom tried, she couldn’t either. Then that anger turned inward, and in a state of confusion, he hurt himself to cope.

What made it harder, Fitzgerald said, was the need to “cover up” his addiction to cutting by wearing sweat jackets whenever he left his bedroom, even in the hot summer. It made him stand out as “the one who wore hoodies.”

Fitzgerald said he proudly stood out in other ways, too, by dressing flamboyantly like RuPaul and Jeffree Star, but it painted a target on his back for bullies who wanted to “teach him a lesson.”

Experts say that flamboyant cross-gender dressing and gender nonconformity is, to a large extent, a focus of much anti-gay bullying. Swearer and colleagues say a possible explanation for the bullying of gender nonconforming individuals can be derived from a theory of moral disengagement, in which the bully dehumanizes and blames the victim for the bullying.

Anyone labeled “gay” then is “deserving” of what they get. They deem it to be justice.

Gender expert Michael Kimmel of State University of New York at Stony Brook said such schoolyard bullies are often the most insecure about their own masculinity and have to prove it by bullying someone who is no real match. But because it proves nothing to pick on someone not your own size, they have to do it over and over again.

Fitzgerald falls in the category of “someone not your own size.”

By the end of junior high school, Fitzgerald was openly dating both boys and girls and hanging out at the Grapevine Mills Mall with a group of friends that got high together. Though Fitzgerald dabbled with a litany of drugs, he said his “main focus” was amphetamines — speed and ecstasy.

It landed him in the Lewisville emergency room and under heavy watch for drug use. But that wasn’t enough for the young man to hit rock bottom; that came later when heroine put him into detox and recovery for two months.

“I told my mom I sincerely need help,” he said, “and I started getting on the right track.”

It was a cry for help and Fitzgerald got it, back in Lewisville. He wanted acceptance from his dad, too, who thought his son was “selfish for wearing makeup.”

Fitzgerald, whose parents are divorced, said he is getting along greatly now with his father, who regularly tells him: “You are who you are.”

Fitzgerald said eventually he was able to wear makeup, be androgynous or wear pink blush and paint his brows and his father finally got used to it. With the help of a good therapist, he said, the family finally was able to pull together, including Fitzgerald’s stepfather.

Fitzgerald also credits his recovery to going to Youth First Texas when he was 14. He said that Bob Miskinis, the former program director, would stay on the phone with him for hours and help him work through the issues that were haunting him.

YFT was the “height of my happiness and has been nothing but a blessing,” Fitzgerald said.

But it didn’t last. The bullying he was then enduring was miniscule compared to what would come at Flower Mound High School.

New school, same old problems

Before his first day at Flower Mound, Fitzgerald said he was cyber-bullied on Facebook with taunts like “Get ready for hell,” and “Can’t wait to meet you faggot.” Fitzgerald said he was cross-dressing then, and the fact he was gay “got to them [the bullies].”

When he started school at Flower Mound, Fitzgerald said, he was shoved into walls, kicked and punched.

“Every time I walked down the hallways, I had to worry about what somebody may say or do to me,” he said. “And I started to get anonymous death threats.” Echoes of the hatred would go through his mind repeatedly: “I want to kill you faggot. I will throw you in a tree and cut you in half with a chain saw.”

Fitzgerald couldn’t make it alone in school. He had friends to support him, to walk him through the hallways, to keep an eye out for him, and to let him know what was “going down.” He carried a hidden can of mace for his protection, something that was against school policy, but he risked it because he was afraid for his life.

No one helped, he said, adding he was treated like a disposable troublemaker. His guidance counselor was his best help, but was only able to recommend summer school so Fitzgerald could get done with school sooner.

His coach warned the bully to stay away. The bullying was still brushed off as not serious and verbally abusive comments were dismissed, Fitzgerald said.

No one recognized the crisis situation Fitzgerald was living in. And a year after overdosing on heroine, plagued by worries that he would be killed with a chain saw, Fitzgerald fell off the wagon and found himself an inpatient in a

Lewisville hospital again, this time with a blood alcohol level of 0.23.

“In a sense, my school approved of the bullying by being silent,” Fitzgerald said, adding that there was no support to right the balance of power among peers.

For example, Fitzgerald said, six times officials at the high school denied requests for the formation of a gay-straight alliance. It was a message that told gay youth they didn’t matter,” he said.

And on the National Day of Silence, Fitzgerald said, students were denied permission to wear gray tape over their mouths to bring visibility to their plight.

New school, new hope

The good news for Fitzgerald is that he has found peace at iSchool High in Lewisville, a private school with about 250 students.

He said he loves the teachers, who are very structured and have zero tolerance for lack of mutual respect. Fitzgerald said the reaction to bulling at iSchool goes beyond just policy; school officials actually stand by their words.

Fitzgerald, now 16 and a sophomore, is on “the right track,” he said. He said has two goals in life: to be a cosmetologist and to pursue his music writing. Of course, he also wants to have “a lot of money and a hot husband.”

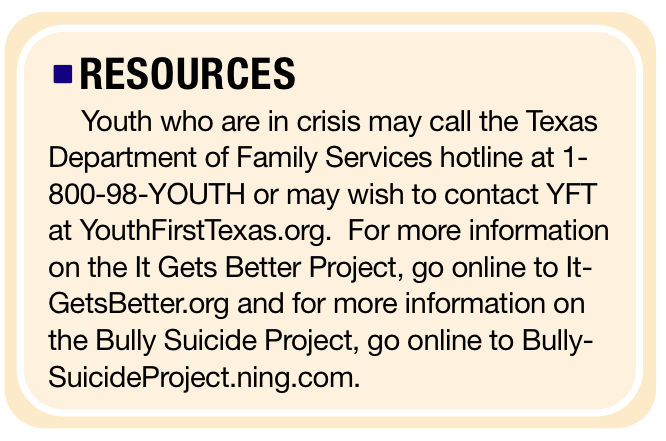

Fitzgerald said he is becoming more active about LGBT equality and overcoming bullying in schools. He has been on the radio, participated in the Bully Suicide Project and, also, the It Gets Better Project.

It’s something he is dead serious about: “Some of us are treated as second-class citizens, and I’ll stop at nothing, even take a bullet if I have to, for the sake of LGBT equality.”

Renee Baker is a Case Manager at North Texas Youth Connection and serves on the Advisory Board at Youth First Texas. She may be found online at Renee-Baker.com.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition Jan. 21, 2011.

Fitzy, I am so proud of you. It takes a lot of courage to give this kind of interview and put yourself out there like that. I am so glad you did it. People need to know they’re not alone. You are truly a personal hero. I look up to you so much. Your courage and strength inspire me to be stronger. I love you so much!

Bullying sucks! I actually had my last bullying incident in High School a week after graduation, while picking up my diploma. Far too many people just don’t get the lasting effects bullying has. Fitzy, you go girl! (Or guy, I dunno what you prefer) I admire you for being so vocal here about your experiences, too many of us just wanna hide.

Having known Fitzy since he was 14, I must say he has been the epitome of grace and courage while enduring a society that has been hesitant to understand him. Not only has he discovered healthy coping mechanisms, but he also is a fantastic role model for other youth who are struggling. I have witnessed him inspire others by being his genuine self. I believe we can all learn something from his story. We are so proud of you, Fitzy. Thanks for sharing your journey as you are one of my personal heroes in this life.

Fitzy , I admire the strength and courage that you showed in being what you are and not letting anyone or anything change that . I know all too well from my own personal experience what it was like being bullied in my youth for being bisexual or different. It is these differences that make us who we are and i believe that everyone has a right to be true to themselves…You are a hero and inspiration to the people who have been there and those who are there now….I believe people can make a positive difference in other peoples lives through their actions and choices….Keep up the good work and your wonderful labor of love…And may you continue to touch many hearts and many lives for many many years to come…>(^-^)< The Lady SkyKatt RavenTail

It’s about time we are told about the horrible things that bullies can cause! I’m proud of Fitzy for coming forward telling his story! If we don’t get this out in the the open things will never change! Although this is about gay bulling or gay bashing lets not forget there are all kinds of bulling and none should be tolerated!!

You are absolutely on of my gay icons. Your story (and other storied like these) will give light to those being bullied, and will help slow it down, if not stop it altogether. Thanks for being strong and not giving up! Way to go, I’m so proud of you girl 🙂

Like Judith, I have also had the pleasure and honor of knowing Fitzy since he was 14. So many of us did not know who we were at his age and, if we did, most of us were too afraid to acknowledge the truth. Fitzy has found his comfort in being who he is both inside and outside — unashamed, unapologetic and fabulous at the same time. I’m so happy to know him and to know that he survived his darker days to shine as beacon of light and hope for other LGBT teens today and in the future.

I’m so proud of you for standing up for your rights. i love and adore you so much.