Cedar Springs and the gayborhood continue to transform themselves just as any good 40-year-old diva would

The news flew up and down Cedar Springs Road last week, and within an hour, thousands of people had shared on Facebook and through text messages that after more than 40 years in business, Richard Longstaff was closing Union Jack.

The online comments reflected community members’ sorrow over the loss of a business that through the decades has stood guard over a street now synonymous with Dallas’ LGBT community.

“So sad,” commented Juan Lucero. “You were always friendly and helpful and the one constant place on the block.”

And Union Jack was, if anything, constant.

In the early 1970s, Cedar Springs wasn’t the gay asphalt ribbon that had taken its place in the gay lexicon, along with Westheimer Road in Houston. In those days, it was just another Dallas street, but when Longstaff, a Brit, planted the Union Jack and marked his territory, he unknowingly began the street’s transformation into a corridor that today takes people through the heart of gay Dallas.

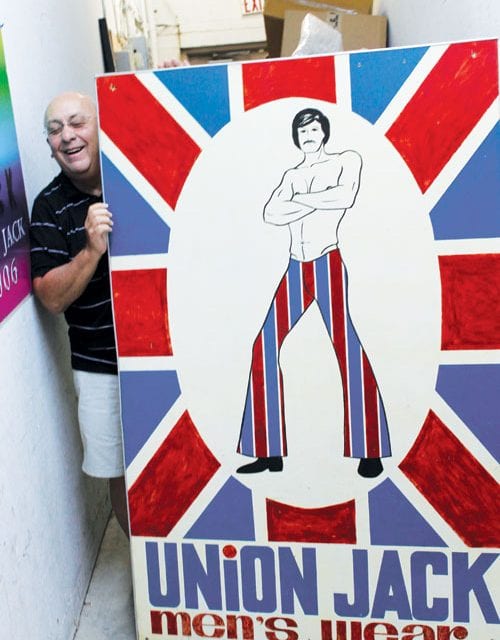

HISTORY | The original Union Jack sign depicts ’70s gay fasion. The store, open for more than 40 years on Cedar Springs, is closing, its owner Richard Longstaff recently announced. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

The establishment of a gayborhood didn’t begin with the idea of creating one. Cedar Springs simply evolved as gay-owned businesses occupied the worn buildings.

In 1978, a few years after Union Jack opened, Throckmorton Mining Company flung its doors open as the first gay bar on Cedar Springs, by way of Throckmorton Street. Not everyone was happy about it. Longstaff remembers that when he put go-go boys in the window as a promotion, the employees of Adairs, a redneck bar across the street, called the police. Still, the gay business owners held their ground, and the stirrings of activism quietly began to grumble.

The Bronx, the first gay-owned restaurant opened in 1975. In 1980, J.R.’s Bar & Grill opened and was joined by TapeLenders. As a testament to its longevity, TapeLenders’ inventory has run the gamut from Betamax to VHS to DVDs, sprinkling gifts and T-shirts in the mix.

After The Container Store moved from the corner of Cedar Springs and Throckmorton, Hunky’s moved in, and the iconic hamburger joint anchored the neighborhood.

With the offerings of shopping, restaurants and clubs, Cedar Springs’ identity as a gay enclave grew. In the ’70s and early ’80s, Southwest Airlines offered “peanuts fares,” selling tickets for $25. Gay men from all over Texas and the surrounding states flew in to Dallas each weekend, filling Cedar Springs with the energy and excitement of the newly liberated.

The music of Donna Summer, the gay siren of that era, rocked The Old Plantation, and men in platform shoes and bell bottom pants watched the street’s activity from the club’s second-story balcony. The smell of amyl nitrate, commonly called poppers, waffed across the dance floor.

The Old Plantation never really went away. Today, S4 occupies that space — and more — but the strip has been an ever-evolving gay landscape.

Crossroads Market, located where Hunky’s and Subway are today, is an example of Cedar Springs’ evolution. A group of activists rented portions of the building, and each offered something different: antiques, jewelry, picture framing, greeting cards, books and gifts. The store was eclectic and bohemian. In its last two incarnations, it was a modern bookstore and finally a coffee shop. Longstaff was its final owner.

The Bronx closed two years ago. The Melrose Hotel bought the building and then tore it down. Additions to the hotel, including a larger ballroom are scheduled to be built on the property when the city of Dallas grants a zoning variance. One hold up is the alcohol license.

Part of the space is zoned for alcohol, and another part isn’t, so someone getting a drink on one side of the room won’t be able to walk across the room unless the entire area is zoned wet.

Down the street, the supermarket known affectionately to the community as Mary Thumb was uprooted by a Kroger that opened across the street, offering lower prices in a modern shopping environment. Mary Thumb was razed, and developers built ilume.

But Cedar Springs wasn’t all bars and shops selling hilarious greeting cards. The winds of activism blew into the community, and the street became ground zero for organizations fighting bigotry and then — AIDS.

Along with Bill Nelson, Longstaff helped found Dallas Alliance for Individual Rights that predated Dallas Gay Alliance. Longstaff and bar owner Frank Caven were usually the faces of DAIR, demanding equal rights and a stop to the police raids. They could afford to protest publicly because as business owners, they couldn’t be fired.

Longstaff recalled early TV news reports on the LGBT community were always filmed in front of his store. At the time, the clubs didn’t have windows, but Union Jack had large showcase windows whose displays screamed “gay.”

Those were the days before the Internet, so the best way to find what you needed in the gay community was to call a local help line. Counselors who manned the line also helped callers who were struggling with coming out issues. The phone line was located in the back of the DGA office, which moved to Cedar Springs in the early ’80s.

“We paid the phone bill for years and years for the gay helpline,” Longstaff said.

Former Dallas Gay Alliance president Bruce Monroe remembers the long, narrow space the organization rented, which is about the left half of the current Union Jack location.

“The old shotgun community center was home for so many years,” Monroe said. “When we needed to get word out about an event, we’d set a table out front. In the ’80s and ’90s, you couldn’t walk down the street without being confronted with gay rights.”

As the AIDS crisis grew, DGA created the Resource Center and began offering services, including health care at its Nelson Tebedo Clinic.

AIDS Healthcare Foundation Texas Regional Director Bret Camp worked at the clinic for 20 years.

“The Nelson Tebedo Clinic was an important location for the community,” he said. “It was a safe place offering services not available anywhere else.”

Camp said offering those services on the street was a way to eliminate barriers to service, but when the clinic opened, it was the only safe place to get an HIV test. In addition, the Resource Center offered pentamidine mist treatment to prevent Pneumocystis, the most common opportunistic infection that was killing people with AIDS.

The drug wasn’t approved for that treatment, so the clinic was the only place in North Texas where people could receive it.

Also, when the Nelson Tebedo Clinic began offering dental services, it was the only place for many people with AIDS to get any dental treatment.

“AHF couldn’t be in North Dallas today if it wasn’t for the Resource Center and the Nelson Tebedo Clinic on Cedar Springs,” Camp said.

In some ways, Longstaff’s retirement is something for the community to celebrate. So many of the previous club and store owners died during the AIDS epidemic. Hunky’s passed from David Barton to his brother Rick. A flower store where Buli stands closed when its owner died. The Round-Up Saloon sold before Tom Davis died. Dave Richardson continued operating TapeLenders when his partner Steve Freeman died.

Crossroads owners Bill Nelson and Terry Tebedo died, and co-owner William Waybourn sold his share when he moved to Washington, D.C., to found the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund.

But after 42 years of operating a successful business, Longstaff is, indeed, retiring.

“I hate to hear it,” said Dale Holdman, owner of OutLines. “When I came out, Union Jack was there. Richard’s been nice to us ever since I bought OutLines five years ago.”

But as one store closes, four others are opening. Richardson, who now owns Skivvies, opened Gifted just before Christmas.

“I’m trying to bring variety back to the street,” he said.

Gifted is the first gift store on Cedar Springs since Nuvo recently moved to Oak Lawn Avenue. Richardson lamented the closing of Union Jack and said Longstaff is revered, but he looks forward to new businesses opening on the street.

“I hope he enjoys his well-deserved retirement,” he said, “but change is good. New stores add variety and keep the street interesting.”

Longstaff agrees.

“This store is part of the ’80s ghetto,” he said. “Let’s move away from that.”

Kasey Parmentier didn’t experience the ’80s on Cedar Springs, but the 19-year-old student has been going to the strip for three years, the first time for Pride.

“I didn’t know what to expect when I went to my first Pride,” he said.

Not allowed to watch Logo, the gay TV network, at home, Parmentier had nothing to prepare him for his first visit to the gayborhood.

“I saw drag queens roaming the streets, men in leather, gay happy couples with children,” he said. “Everything the gay world has to offer.”

Parmentier called Cedar Springs its own little world, and he’d like to see another one-of-a-kind shop replace Union Jack.

“If Cedar Springs wasn’t there, I’d probably move to a city that had something like that,” he said.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 10, 2014.

[polldaddy poll=7705415]