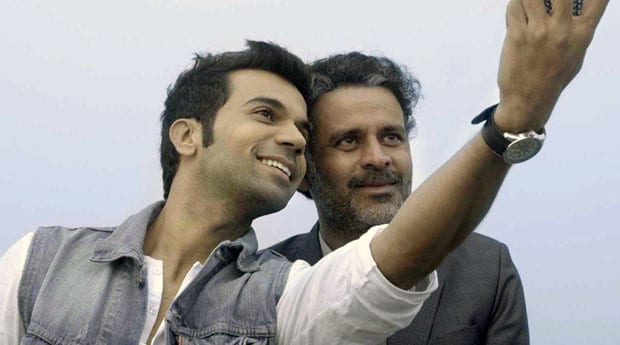

DFW’s South Asian Film Festival explores the taboo of being gay in India in ‘Aligarh’

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

Apurva Asrani remembers the day (really the moment) that he first heard a story that would encapsulate the risks of being gay in India … and forms the core of his first screenplay.

“I was on a news debate about societal attitudes towards homosexuality [when] the news [broke] of the death of Prof. Siras,” he says. “It was then that I [first] learned about this college professor.”

In a scene almost out of Lawrence v. Texas, Prof. Siras became a cause celebre when two cameramen broke into his house and filmed the middle-aged academic having sex with a male rickshaw puller. Instead of taking action against the intruders, the conservative university where he worked, Aligarh, suspended Siras, who was humiliated and harangued for the next two months, until he died.

In a scene almost out of Lawrence v. Texas, Prof. Siras became a cause celebre when two cameramen broke into his house and filmed the middle-aged academic having sex with a male rickshaw puller. Instead of taking action against the intruders, the conservative university where he worked, Aligarh, suspended Siras, who was humiliated and harangued for the next two months, until he died.“The story broke my heart,” Asrani says, “and made me very angry.” As the news quieted down, people began to forget about it … including Asrani. Then last year, a stranger sent an email to Hansal Mehta, a film director for whom Asrani had worked as an editor. The sender suggested that Siras’ story would make a good film.

“When I heard about this email, I thought it was providence that this story should find its way back to me,” Asrani says. “So I began to write it as my debut feature script.”

The resulting film, Aligarh, receives its North American premiere this Sunday at DFW’s South Asian Film Festival. It’s a major coup for the gay-run festival, as the film is creating a buzz just as it rolls out for an international release.

The buzz has been, unexpectedly, both positive and negative. Some of Siras’ family members have slapped the filmmakers with a lawsuit for defamation for calling Siras “gay.” And India’s Censor Board of Film Certification has bestowed an A (adult) certificate — the U.S. equivalent to an MPAA R-rating — meaning given the film and its trailers may not be shown to children and family audiences. “There are also groups in the area where the film is set, protesting against associating their city with homosexuality,” Asrani says.

But the objections have only served to raise the profile of the film … and trigger an outpouring of acceptance as well.

“All of this has brought our prejudices into the forefront, and somewhere, that is exactly what the film intended to do,” Asrani says. “Simultaneously, our first trailer has met with an amazing response. Within three days, it went viral. So many people made it their own cause. They protested against the censor board, they sent us messages of love and support. I had so many messages from closeted gay folk thanking me for bringing a non-stereotypical gay protagonist into the mainstream.”

It’s a personal achievement for Asrani as well, who is openly gay. (He and his partner celebrated their ninth anniversary earlier this week.)

“It has taken time, but we now enjoy the support of both our families. But for most gay people in India, the blessings of one’s parents is a distant dream. What adds to society’s lack of understanding is the terrible stereotyping of gay characters. They either portray us as over-the-top buffoo

ns — used as an object of ridicule — or as uni-dimensional sex maniacs,” Asrani says. “There are maybe one or two gay portrayals done with a sliver of dignity, but society doesn’t want to see us in the mirror they hold up … unless of course it’s one of those funny mirrors.”

Asrani also brought his own experiences with discrimination into the script. In one scene, Siras’ irate landlord asks him to vacate the house — not by calling him gay, but by pretextually insisting “bachelors aren’t allowed to live here.” “That’s how it’s done here,” Asrani sighs. “We can’t even call homosexuality by its name. We are too embarrassed to do that.”

A subplot deals with India’s caste system (“The university’s lawyers deem his union with the rickshaw puller as dirty,” Asrani explains. “They first wondered how he could have gay sex, and that too with a lower caste Muslim!”), but that is not the film’s central theme.

“At the heart of the film is a dignified senior citizen who wants to exercise his constitutional right to his privacy and dignity. Siras is not a crusader; he is a shy poet, in love with his writing, with old Hindi film music and his two glasses of whisky. The case our film makes is that nobody has a right to invade or probe into his private sanctum.”

In some ways, that makes the marketing of the film in India — its tagline includes the hashtag #ComeOut — even more amazing.

“The #ComeOut campaign [is] not referring to only LGBTQ people, [but] the entire nation that is silent on this massive human rights violation,” Asrani says. “It is urging everyone to come out and support equal rights. ‘Coming out’ as gay, lesbian or bisexual in a country that can send you to jail for 20 years isn’t an easy task. But I think it’s high time we all realized that we are more vulnerable in our closets than we are on the outside, standing tall with our brethren.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February 19, 2016.