Showing support for the social justice unit on the night of the Irving Schools Foundation grant presentation in March 2018 were, from left, the Irving High principal, the school’s English Department chair, English teacher Anna Waugh, English teacher Carol Revelle, an English Pre-AP teacher and an English I teacher. Revelle and Waugh were instructed to pack the books up to send them back after word came that there had been a complaint about the LGBT-themed book. (Photo courtesy Anna Waugh)

Irving ISD administrators blocked use of LGBT graphic novel

Anna Waugh | Special Contributor

annamwaugh@gmail.com

In the spring of 2018, my English I team at Irving High School decided to create a social justice graphic novel unit based on interests of our students.

What followed was the sudden removal of all six novels from the unit because of one LGBT-themed text. This was followed by silence from leadership, an eventual cover-up by the district, and a new policy gatekeeping teacher-selected materials.

It is only recently, as my former coworker, Carol Revelle, and I compiled some research on the story for a book about LGBT curriculums, that we fully recognized how bigoted the process had been.

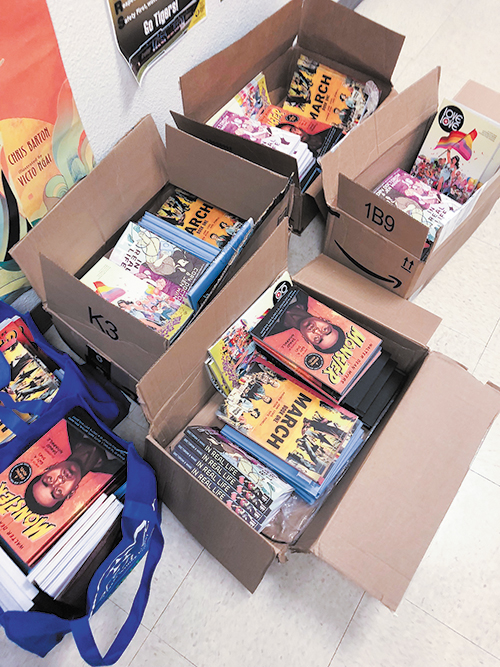

After the Irving Schools Foundation provided a grant for their purchase, the graphic novels — March, Speak, Monster, Love is Love, In Real Life and Hidden — arrived and were being laminated to extend their use. The principal entered the room and told us to pack up the books because a complaint had reached the superintendent.

The unit was set to begin in two days. Our team lead, Revelle — who has a doctorate in curriculum and instruction and more than two decades of teaching experience — emailed a letter the next day, requesting an immediate return of the novels and that the district follow its policy for challenged materials.

The unit was set to begin in two days. Our team lead, Revelle — who has a doctorate in curriculum and instruction and more than two decades of teaching experience — emailed a letter the next day, requesting an immediate return of the novels and that the district follow its policy for challenged materials.

No response ever came.

We purposefully chose books on topics our freshman students could relate to — bullying, sexual abuse, child labor, violence, the prison industrial complex and bigotry — because circulation date demonstrated that students were checking out three graphic novels to every five fiction books. We planned to have students self-select two from the set.

Furthermore, we had overwhelming support. Our principal suggested seeking funding through the foundation, and she, along with our English department chair, two grade-level teachers and a district curriculum advisor, attended the grant presentation that Revelle and I made to receive the grant.

But the support there at the beginning quickly fell away once the books were challenged. Our emails and requests to meet were ignored. Meanwhile, a committee comprised mostly of librarians and the superintendent, who was not listed in attendance but called the meeting that met in his conference room, decided to ban the LGBT book.

Our librarian repeated a rumor that the committee took issue with the novel’s “extreme homosexuality.” I have thought long and hard about that description and can only say that it’s a hateful depiction for a graphic novel that memorializes the victims of the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, and that proceeds from the sale benefit the survivors of the deadliest attack on the LGBT community in U.S. history.

The text is tasteful and respectful and, sadly, representative of this tragic event in our community’s history.

By the end of the school year, the banning of Love is Love was official.

Officially, no professional reviews, paperback-only format and “mature content” sentenced it to banishment. Yet many books are used Irving ISD without professional reviews, especially graphic novels that often don’t get reviewed at all.

Other books in this unit were also paperback, and they were all retained. As for “mature content,” the back cover does suggest it be for “mature readers,” yet high school falls under that category.

After Revelle and I secured new jobs over the summer, I reached out to Rafael McDonnell at Resource Center. He contacted state Rep. Rafael Anchia, whose staff only secured a meeting with the superintendent after a sit-in. At their September meeting, Superintendent Jose Parra claimed ignorance of the events, despite reported multiple-hour phone calls with our principal about the matter and the fact he hosted the review committee.

Less than a week later, he resigned at the board’s request. No reason was publicly given.

Emails went back and forth between the district’s legal counsel and McDonnell, but the district held firm to the ban, citing a new policy that requires six-weeks’ notice for non-approved texts. This was not the policy in spring 2018, and it can only have been created to prevent future LGBT-inclusive texts.

Additionally, the district is concealing this ban by not listing any of the graphic novels as challenged or Love is Love as banned in its records. In fact, the information obtained from the district is incomplete, as these events, as well as at least two emails, are known to be missing from records requests.

There are many avenues to fight book bannings. We chose to tread lightly and try to work within the system.

After the ban, we contacted the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, but that organization needs someone associated with the school — a teacher, student, parent — to make the complaint to reverse the ban. Because Revelle and I are now employed elsewhere, I reached out to the school’s GSA advisor to see if she or the students could take on the fight with us. She spoke to another member of the team still employed who wouldn’t even talk about it, giving her, she said, the impression she needed to “keep it quiet.”

I was angry at that, yet I had waited until I had a new job before advocating for the text. We also contacted the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom. At this point, we want the graphic novels repurchased and united with the set, and we want the new gatekeeping policy removed to allow teachers the ability to choose texts, including LGBT texts, for their students.

I wish I could go back and fight harder from the beginning, but I can take away countless lessons from my first book-banning experience as a teacher and realize, as a masters of library science student, that those librarians failed students when they let their biases override their professional judgment.

At the end of the day, the LGBT students of Irving ISD deserve to see themselves represented in the curriculum and to have their stories told, not erased like the district has done with its recordkeeping.

Anna Waugh is a lesbian high school English teacher in DFW and is a masters of library science student at Texas Woman’s University. She can be reached at annamwaugh@gmail.com.

Anna, I hope you do not let the close-mindedness of a few keep you from pursuing what is a beneficial book. Have you thought about providing your books to other school districts? Just a thought. Good luck, as you deserve it!

The books are still in our classrooms, they were never removed. I had half a dozen students read Love is Love on their own time last school year.

The district’s legal counsel assured Resource Center Dallas the books were not approved and were returned to Amazon. Even our principal informed Revelle and me that the book would not be returned to the school, so if some were mixed in when the other graphic novels were returned, be grateful the district hasn’t found out and removed them like they removed all the books before the unit began.