After two years of celebrations in Lee Park, Dallas’ Pride committee decided to add a parade in 1984

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

The headline in the Sept. 14, 1984 Dallas Voice was “AIDS Vaccine Close to Reality.” The next week, the headline read “The Big Event: Pride III.”

For the first time, Pride in Dallas included a Pride parade. It wasn’t until the second year that the name changed to the Texas Freedom Parade, and then 10 years later renamed for its founder and organizer, Alan Ross.

While several small parades were held downtown and in Oak Lawn during the 1970s, the annual parade as we know it today began in 1984 as part of that third annual September Pride celebration.

In September 1982, a celebration that later became known as Pride I was held in Lee Park to celebrate U.S. District Judge Jerry Buchmeyer’s ruling declaring Section 21.06 of the Texas Penal Code, aka the Texas Sodomy Law, unconstitutional for the

Northern District of Texas the previous month (August 1982). Pride I included political speeches and lots of beer.

That was a time before Facebook and Twitter and even a decade before email. The first issue of Dallas Voice was two years away.

The Dallas Morning News wouldn’t print anything about the LGBT community, and the only thing the Dallas Times Herald printed were license plate numbers and names of people parked at gay bars with the intent of getting them harassed and fired.

There was no monument on the corner of Cedar Springs and Oak Lawn for the community to gather round and celebrate within hours of a monumental event.

There was no monument on the corner of Cedar Springs and Oak Lawn for the community to gather round and celebrate within hours of a monumental event.

To start spreading the word, Crossroads Market owner William Waybourn bought several copies of Buchmeyer’s ruling from the Government Printing Office. Waybourn then made more copies, distributing them from his store at the corner of Throckmorton Street and Cedar Springs Road. Then organizers made fliers, posting them in bars and around the neighborhood to get people to the park.

As word of the decision spread, the gay and lesbian community decided this was something to celebrate. Posters were printed and distributed to bars on Fitzhugh Avenue, Lemmon Avenue and the area around what is now The Crescent as well as on the new strip that was developing on Cedar Springs Road.

Dallas Gay Alliance got out its phone tree and started calling people to let them know there would be a celebration in Lee Park on the third Sunday in September.

Hundreds of people turned out to hear community leaders like Waybourn, Bill Nelson, Louise Young and others talk about the monumental decision that meant, for the first time, gays and lesbians weren’t criminals in North Texas.

The celebration was such a success that DGA staged Pride II the next year.

Pride II in 1983 still didn’t include a parade, although parades were becoming the norm around the country. Indeed, Fort Worth celebrated Pride by staging its first parade that year. The Dallas celebration moved to the bar parking lots on Cedar Springs Road.

For Pride III, Dallas Tavern Guild, which continues to stage Pride, sponsored “The Big Event” in the parking lot behind 4001, the Caven disco that took up the building that now houses Zinni’s, Gifted and Skivvies.

Booths operated by Tavern Guild members raised $3,000, covering the cost of staging the event. The cost of the parade and festival today is more than $150,000.

But that year, Pride for the first time included a parade. It began at the Oak Lawn Library, then located in the center of what is now the Kroger parking lot, and ended in Lee Park.

More than 50 organizations and businesses participated in that first Pride parade. Texas Gay Rodeo Association Color Guard led, followed by the Oak Lawn Band. The Montrose Symphonic Band marched midway through the parade, but the two bands played together at the Festival in Lee Park. They had performed together earlier that year when they marched in the Los Angeles Gay Pride Parade.

That first year, there weren’t grand marshals. About 6,000 people attended. The Round-Up Saloon won an award for best float.

Among the speakers in the park was District 2 City Councilman Paul Fielding, best remembered for running a nasty, homophobic campaign against DGA President Bill Nelson before coming out himself.

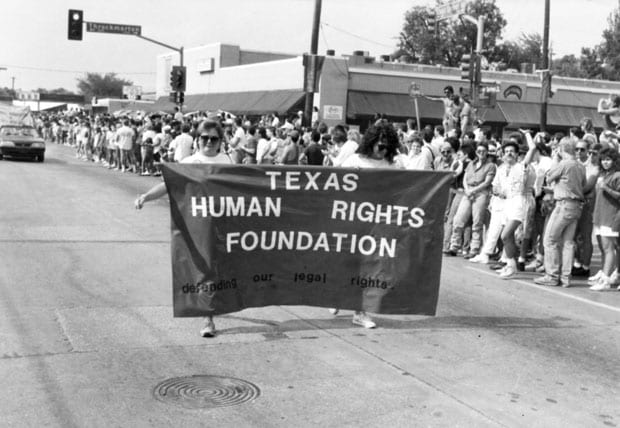

By 1985, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals had overturned Buchmeyer’s decision, but the community remained optimistic. The Texas Human Rights Foundation, a statewide equality organization unrelated to the current Equality Texas, was prepared to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. However, there was enough doubt in the community that the Pride committee held a vote before deciding whether to hold a parade that year after the legal setback.

Pride won the vote: Organizers believed the Texas Freedom Parade was no longer about celebrating the Buchmeyer decision, but had come to be about a growing sense of pride in the Dallas’ LGBT community.

That was the year the first grand marshals were chosen. Oak Lawn Counseling Center founder Howie Daire and author Rita Mae Brown were tapped for the honor. Brown was in town to receive the Humanitarian Award, now known as the Kuchling Humanitarian Award, at the Human Rights Campaign’s “United Our Way” black tie dinner — as it was called then — at the Fairmont Hotel.

In addition to bands from Houston and Dallas, the Mile High Freedom Band from Denver, the Texas A&M Gay Marching Band and Gay Band of America performed in the parade.

After the Buchmeyer decision was overturned by the Fifth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal. But the court did hear a similar case from Georgia that affirmed the Fifth Circuit’s reinstatement of the Texas sodomy law. Yet Buchmeyer was vindicated in 2003 when the Supreme Court ruled in the Lawrence v. Texas decision that sodomy laws were unconstitutional.

Through it all, Dallas’ LGBT community has continued to gather each September for the Alan Ross Texas Freedom Parade, now in its 32nd year. From the 50 entries in that first parade in 1984, it has grown to 89 paid entries this year, more than 120 counting the sponsor and VIP entries

Thousands are expected to line the parade route this year — which still starts at the intersection of Cedar Springs Road and Wycliff Avenue — and just as many are expected to gather in Reverchon Park for the after-parade festival.

What started as a celebration of a judicial victory has persevered through the dark years of the AIDS crisis and legal losses to come out on the edge of a bright new future for a community that has, through it all, maintained its pride and its hope.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 18, 2015.