Trans veteran fights past the pain to live openly at last

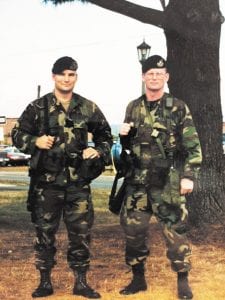

Brenda Lawrence served in the Air Force and Reserves for 28 years total. She was discharged in 2012 and began her transition last year.

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

“They are already making changes,” retired Air Force Master Sgt. Brenda Lawrence said this week of the U.S. military’s stance on transgender servicemembers, just days before Defense Secretary Ash Carter announced Thursday, June 30, that the Pentagon is officially lifting the ban on open service by transgender people.

She held up her military ID card: “See? That’s my female photo right there on my ID. In 2012, when I left the Air Force, that wouldn’t have been possible.”

The card still bears the male name that Brenda was given at birth, the name she was known by during her military service and which remains her legal name. But, she said, as soon as her divorce from her wife is final, she will be legally changing her name and the gender marker on her identification. And thanks to the changes in Department of Defense policy, she expects to be able to change the information on her military ID then, too, without any problems.

Brenda began transitioning publicly only a little more than a year ago. But she has known all her life that who she was on the side did not match the body she had to wear on the outside.

“I’ve known since I was very little. This did not happen suddenly,” Brenda said of her gender identity.

“I remember, when I was little, having a conversation with some adult — I don’t remember who it was — and they said something about me growing up to be like my daddy. I said, ‘No. I’m gonna grow up to be like Mama.’

“But I learned pretty quick to keep my mouth shut about those things,” Brenda continued. “I tried to be a good child, to listen and do what I was told, to do ‘the right thing.’ I learned to hide it, to hide who I really was, to not let anyone know who I really was.”

After signing up in late 1983 for delayed enlistment, Lawrence — then still identifying and presenting as male, even to herself — joined the Air Force in February 1984 and headed off to basic training. Four years later, while stationed in South Korea, she finished her enlistment term and separated from the service. But she chose to stay in Korea for awhile, working with missionaries at a Baptist church there.

After signing up in late 1983 for delayed enlistment, Lawrence — then still identifying and presenting as male, even to herself — joined the Air Force in February 1984 and headed off to basic training. Four years later, while stationed in South Korea, she finished her enlistment term and separated from the service. But she chose to stay in Korea for awhile, working with missionaries at a Baptist church there.Upon returning to the States, Brenda spent a semester at Bob Jones University — “one of the most conservative schools in the country; they didn’t even allow interracial dating when I was there” — but she couldn’t stay. She worked for Eastern Airlines for a while, but like other employees, was left high and dry when the airline closed.

She ended up in Mobile, Ala., when her father got her a job with a company he had worked with. That job didn’t work out well, and she moved on to teach at a private Christian school. In the meantime, she met, fell in love with and married the woman she would spend almost 25 years with. They were married Dec. 15, 1990. In November 1991, their first child was born.

In 1992, while still teaching, Brenda joined the reserves, working as a combat arms instructor and armorer. In 1996, she cross-trained into the security forces, and in 1997, she went back on active duty.

She was stationed in Massachusetts for a year and then her whole unit was moved to Carswell Joint Reserve Base in Fort Worth.

In 2002, Brenda was transferred to Robbins AFB in Georgia for three years until, in 2005, “I was given the chance to go anywhere I wanted. I chose to come back to the Dallas-Fort Worth area,” she said. “I just really liked it here.”

Back then, Brenda said, “I was presenting very conservatively. I am the last one anyone would have expected to transition.”

In fact, she added, like many other trans women, “I spent all those years doing everything to deny who I was. I became just hyper-masculine, trying to change. Most trans women who go into the military before they transition go in to prove they are men. Most trans men who go into the military go into the prove they are men.”

She said that while she had always been slight of build with a relatively high-pitched voice, she fought hard to change that, working out hard to build muscle mass, to beef up her slight frame. She also worked hard to lower the pitch of her voice, and ended up being so successful at it that today, she can’t even hit that higher register when she tries.

Brenda said that during those years of fighting her identity, she was “really very fierce and adventurous.” She boxed. She wrestled. She trained in martial arts and earned a black belt in Tae Kwon Do.

“When we trained, nobody wanted to go up against me,” she said. “Nobody wanted to get on my bad side. I was just fierce.”

But through it all, the reality of her identity remained. “I was always fighting it,” Brenda said. “I hate it. My wife hated it.”

Brenda said that her wife has known since before they were married that she struggled with her gender identity. She said she told her parents about her battle in 1992. But as long as she continued to fight it, they didn’t turn against her.

And she kept her secrets carefully hidden from those at the conservative Baptist churches she and her family attended. One of the hardest parts, Brenda said, came “when we would see somebody who was obviously gay, or a trans person. I’d have to say that it was wrong, tell my children those people were wrong. It hurt me inside every time.

“I tried to balance it out by telling them it was wrong, but at the same time tell them we must treat every person with respect and that it wasn’t our place to judge someone,” she added. “But still, it hurt.”

While she was in the military, Brenda said, it was easier to tamp down her inner self as long as she was in an all-male environment. “I could just focus on doing my job then,” she said.

But when she worked with women, it was harder. “I would see these women, and I would get so jealous, especially when they were very feminine women,” Brenda said. “I joined the military to prove how manly I was, to do these masculine jobs [like being a mechanic]. But then I would see these women who were totally feminine and could do these jobs just as well. I was there to be a man, but even with grease on their hands and mud on their faces, they were still feminine women, doing the job as well as any man.

“I would see them, and all I could think was, ‘I want to be like that. And I can’t,’” she added. “I think, really, that when I was promoted and started having more office jobs and being around more women, that’s when my career really stagnated — when I finally began to realize that I am just wired this way, that this need inside me wasn’t just going away, and that I could not be my authentic self and still be in the military.

“I think that if they had lifted the policy earlier, I might still be in the military. I might have gone further.”

In 2012, Brenda retired from the Air Force. And the pressure to stop hiding continued to build. Last year in March, she attended a meeting of the support group DFW Trans-Cendence. It was the first time she presented in public, to anyone, as female.

On July 27 last year, she said, she began medically transitioning. “That’s when my wife cut me off emotionally. Things between us went downhill from there,” she said.

In October, although they had agreed to file jointly for divorce, Brenda said her wife surprised her by having her served with divorce papers at work, and Brenda had to find somewhere to stay. She came out to her supervisors at work — she works at a call center — and “we hammered out a plan then” for her to transition at work.

“I came out to my coworkers just before Thanksgiving, and then my bosses gave me the rest of the week off. I had that time to go and get my hair done, get my nails done, things like that. And when I went back to work the Monday after Thanksgiving, I went back as Brenda. I have been Brenda, 24-7, ever since,” she said.

It has been, Brenda said, “the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I went to Army sniper school and that was hard. But not nearly as hard as this.” She has lost her home, her wife and her children — both her daughters and her son are “following their mother’s lead” in turning their backs on her.

But, she said, “I’m still happier than I have ever been, because I finally get to be me.”

She continued, “I had always lived with this inner frustration because I knew I wasn’t being my authentic self. But when I walked into that Trans-Cendence meeting the first time as Brenda, well, I looked awful, I know. I can look back now and I know I looked awful. But I felt beautiful. I hate looking at photos of myself back then, because I know I looked awful. But I loved looking in the mirror — I still love looking in the mirror — because I could see that part of me that was finally alive! I am alive! Finally, I am me!”

Brenda said she is thrilled to know the ban on transgender people in the military is lifting, because although it is “too late for me, it clears the way for those in the military now and those still to come. I am so glad for my trans brothers and sisters that they no longer have to hide who they are. They can be their authentic selves, and when people are authentic and don’t have to hide, they perform so much better. And when they perform better, our military overall performs better.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 1, 2016.