Victims of bullying wonder why saying ‘faggot’ doesn’t cause the shock waves the N-word or anti-Semitic slurs generate

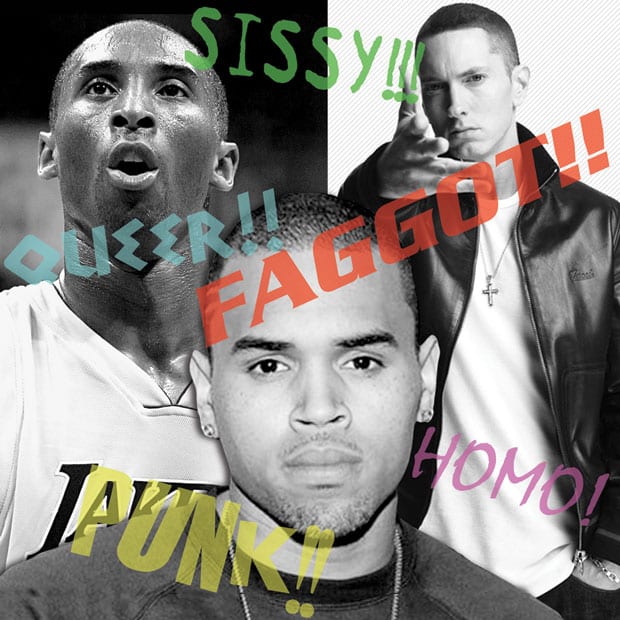

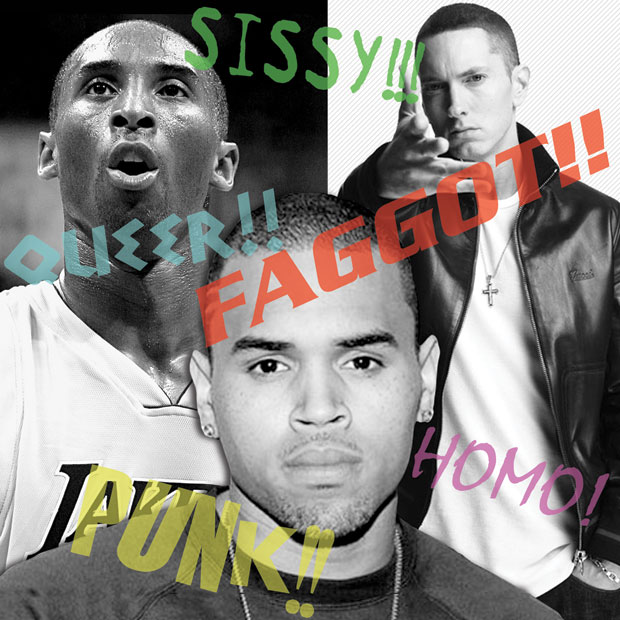

SLURRING THEIR WORDS | In 2011, the NBA fined Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant, left, $100,000 for an anti-gay slur. Chris Brown, center, was recently accused of using a gay slur during an attack outside a hotel, and rapper Eminem, right, received criticism for his gay slurs used in the song ‘Rap God.’

The two-word sentence slammed into Paul Escobar like a train, and years later, the emotional shrapnel still painfully twists into him.

“When I was in school, there was a group of guys who bullied a friend and me,” he said. “They called us names, but the worst thing they said, the one that would really hit home was when they would say, ‘Die faggot.’ Even today when I think about it, I feel sick.”

Escobar’s four years of high school in Houston were a nightmare. He could take the shoving and the mocking, but the polluted anti-gay slurs drilled into his soul’s marrow, weakening his self-esteem and diminishing his worth.

“When they would tell me to die, believe me I wanted to,” he said. “It got to where I couldn’t think about getting through the day. I would tell myself to just get through one class at a time.”

Sometimes, though, he couldn’t, and he’d go home and hole up in his room. Too ashamed to tell his family about the bullying, he suffered alone. The next day he’d return to school to face the assault again.

“It never stopped,” he said. “Those guys wouldn’t let up. I didn’t think I’d make it out of high school alive.”

But he did. Today, Escobar is an accountant in Dallas. His slim frame is perfectly structured for the designer clothes he wears. The hair is working, and his countenance is calm.

“It’s really all just a veneer, though,” he said. “Inside, I’m sometimes still that high school kid. Whenever I hear an anti-gay slur like ‘faggot’ or even ‘that’s so gay,’ I feel like I’ve been hit with a Taser.”

That pain must be continuous because the slurs contaminate everyday conversations, pop music and where sports are played.

In 2011, the NBA fined Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant $100,000 for an anti-gay slur that commissioner David Stern called “offensive and inexcusable.”

After receiving a technical foul during a game, Bryant stormed to the bench, hit his seat before sitting down, threw a towel and then yelled, “Bennie!” toward referee Bennie Adams. Bryant then leaned back and muttered an anti-gay slur. The act was caught on national TV, prompting announcer Steve Kerr to say, “You might wanna take the cameras off of him right now, for the children watching from home.”

More recently, singer Chris Brown was accused of making a homophobic slur during an alleged attack on a man outside a hotel, according to TMZ.com.

“I’m not into this gay shit. I’m into boxing,” Brown allegedly said before punching the alleged victim.

And don’t forget Eminem, who’s facing criticism for his use of gay slurs in his song “Rap God.” The rapper told Rolling Stone magazine he doesn’t think the language is anti-gay but rather a generic insult, “like calling someone a bitch or a punk or asshole.”

Escobar can only stare ahead stoically when asked about Eminem’s excuses. He breathes deeply.

“I was called a bitch, a punk and an asshole,” he said. “And I was called worse, if that’s even possible. Where does that hate come from? But I guess what I’m really wondering is why is society letting them get away with it? If people were using the N-word to insult people, half the country would be up in arms. We listen to this crap everyday, and we just shrug our shoulders and go on.

Meanwhile, thousands of kids are being tormented.”

And worse.

“Billy Lucas was just 15 when he hanged himself in a barn on his grandmother’s property. He reportedly endured intense bullying at the hands of his classmates — classmates who called him a fag and told him to kill himself. His mother found his body.”

The excerpt from a column by Dan Savage, the Seattle-based author who launched the “It Gets Better” project, addresses the continuing problem of using anti-gay slurs as a bullying tool.

“I wish I could have talked to this kid for five minutes,” Savage continued. “I wish I could have told Billy that it gets better. I wish I could have told him that however bad things were, however isolated and alone he was, it gets better.”

Sadly, according to EndOfBullying.com, there are thousands of Billys suffering from unrelenting bullying. The organization says LGBT youth hear anti-gay slurs such as “homo,” “faggot,” and “sissy” about 26 times a day or once every 14 minutes.

A high number, 85 percent, of LGBT students reported being verbally harassed, 40 percent reported being physically harassed and 19 percent reported being physically assaulted at school because of their sexual orientation. Two-thirds, 61 percent, of those students reported they felt unsafe in school.

Still, Josh Wells, a Dallas professional who is straight, says he doesn’t mean anything when he calls someone a “fag” or refers to something as “gay.”

“It’s just how we talk,” he said. “I don’t mean to hurt anyone’s feelings when I say that. Instead of saying someone’s an idiot, I’ll say, ‘he’s a fag.’ Or if something is stupid, I’ll say, ‘that’s so gay.’”

Escobar draws a deep breath.

“Can you really imagine someone thinking it’s OK to use those words and expressions?” he asked. “He’s saying that being gay is so bad and nauseating, it can be used as a synonym for those things. In what world?”

Wells counters.

“I have gay friends, and I’m not in the least uncomfortable around them,” he said. “That language has nothing to do with an anti-gay attitude.”

Daryl Hannah, director of media and community partnerships for GLAAD, disagrees.

“It doesn’t matter whether anti-gay slurs are used to target someone specifically for being gay, for acting outside gender norms or for something completely unrelated,” Hannah wrote in a Jan. 10 article on GLAAD’s website. “What matters is what these words mean to the young people against whom these words are used as weapons, day in and day out, often alongside other verbal or physical assaults.”

And the damage shows.

According to PFLAG, suicide is the leading cause of death among gay and lesbian youth, and about 40 percent of homeless youth are identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual. The statistics continue to sting. PFLAG statistics show gays and lesbians are seven times more likely to be crime victims than heterosexuals, and about 75 percent of those crimes are not reported to anyone.

“A lot of people think they have no one to tell,” Escobar said. “I didn’t think anyone cared. Teachers saw what was happening to me and my friend, and they didn’t do anything about it. I know now there were teachers who would have stepped in had they known, but at that time, I was so ashamed of being bullied. I thought it was my fault.”

Not surprisingly, it was a movie that spurred Escobar to take a stand.

“I was watching To Wong Fo, and there’s a part where this drag queen named Vida Boheme takes on a man who is beating his wife,” Escobar said. “Vida stood up to that bully. At that moment, something clicked, and I thought, ‘I need to stand up for myself.’ And I did. Slowly, but I did.

Escobar’s gained more strength when he became friends with the drag queens in San Antonio where he attended college.

“The drag queens are incredible,” he said. “I love them. They don’t take crap from anyone, and they taught me to be strong and not take crap, either.”

Escobar is working on a graduate degree with the hope of becoming a counselor and an LGBT advocate.

“Because of my experiences, I have a lot I can offer,” he said. “More than anything, right now, I would tell someone who is being bullied or who is hearing someone throw around anti-gay slurs, I would tell them, ‘Get angry.’ I’m not advocating violence, but you have to get up in their faces and let them know you mean business, that you won’t stand for it. Let them interpret what the consequences are. But get angry. That’s what’s going to keep the bullies off of us.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition November 15, 2013.