Gay Fort Worth teen endures endless harassment, assault at school; 3 suspects finally arrested

Micah Moore | Contributing Writer

micahdmoore@gmail.com

EDITOR’S NOTE: An alias has been used for the young man at the center of this story to protect him from further harassment.

Matthew was beginning the school year like any other, excited about the upcoming year. Matthew loved sports and was looking forward to the different sports seasons in the coming school year. Although he was a timid young man, he enjoyed his life with friends and a close and loving family.

But instead of enjoying camaraderie with his teammates, instead of getting to enjoy his classes and goof off with his friends, Matthew found himself facing the harsh realities that come with being a target for bullies. In fact, for two years Matthew endured a relentless, unending barrage of verbal and physical abuse that went unchecked by officials in the Eagle Mountain-Saginaw Independent School District, his parents allege.

Matthew’s parents, a married lesbian couple raising two sons, have been fighting throughout those two years to get the school to stop the bullying. Instead, the harassment continued unchecked, getting worse as time passed.

One of Matthew’s parents Fort Worth Police Officer Sara Straten, a 26-year-veteran of the force now working as a school resource officer in Fort Worth ISD and serving as the department’s LGBT liaison officer. When the bullies targeting her son escalated to incessant verbal and even physical harassment, Straten told school administrators at Chisholm Trail High School she wanted them to file a report with the school resource officer. But 30 days passed without school officials filing such a report, despite her repeated phone calls and email exchanges with counselors and principals.

Recently however, Fort Worth Police arrested three suspects in the case, although two of them appear to still be enrolled at Chisholm Trail High School.

How it began

How it began

In the fall of 2016, Matthew was suiting up for football practice in the locker room when a teammate asked Matthew, loudly and in front of the whole team, if he was gay. Matthew immediately shrank away and tried to ignore him, but the teammate persisted in ridiculing him while some laughed from across the room.

From that day on, Matthew and his family say, three of Matthew’s classmates hurled slurs at and piled abuse on Matthew, who was still coming to terms with his sexuality.

In class, students said things like, “Look at that fucking fag.” Between classes, students would brush shoulders with him, whispering, “Are you gay?” On the basketball court during practice, one teammate shouted, “You’re still a fucking fag,” even as Matthew sank a shot from half-court.

Instead of celebrating wins with his team and enjoying his years in school, Matthew was isolated and alone.

The locker room, the practice fields, the classrooms — nowhere at Chislom Trail High could Matthew find any respite. Instead of being able to stay safely in the closet while coming to terms with his sexuality, Matthew had to face the bullies who were constantly attacking him.

Shortly after the harassment began, Matthew went to the office to speak to the principal. But the principal wasn’t available, so Matthew had to leave a note. The note went unanswered.

And the bullying continued, getting worse through the 2017 fall semester. Then came January 2018, when the abuse changed from just verbal to physical.

From verbal abuse to physical attacks

It happened one day after basketball practice, as students were changing in the locker room, the same day Matthew sank the shot from mid-court.

According to Matthew, two students grabbed him and tried to hold him down. He managed to break free. But one of the boys grabbed him from behind and started dry-humping him while another student grabbed his face, telling him, “You looked beautiful today” and calling him “faggot.”

Finally, the attack ended and Matthew was able to run to the coaches’ office. But no one was there. So he went to the office again to speak with the principal, but left with no reassurance. He had to go back to the locker room to grab his clothes and backpack but then left school without changing.

Megan Overman, director of communications for Eagle Mountain-Saginaw ISD, said in a recent email, “Be assured that anytime a situation of potential bullying or harassment is reported, we investigate it thoroughly in accordance with board policy and our Student Handbook and Code of Conduct, and we work with the families involved in efforts to reach a positive solution for all.”

But the handbook and the code of conduct and board policy provided neither reassurance nor respite for Matthew. In fact, the physical attack coupled with the incessant verbal abuse caused Matthew to retreat back into the closet, and things took a dark turn. He felt more rejected and isolated than ever.

Finally, Matthew went to his bedroom and tried to kill himself, but his older brother found him in time.

“That was devastating,” said Straten. “We knew then we had to take matters in our own hands, since the administration was so absent. Everyone seemed to have turned their backs to the whole situation.”

Matthew’s mothers took him out of Chisholm Trail High School then, choosing to homeschool him for the rest of the spring 2018 semester.

“We hoped giving him the spring away and the summer off, would give him a fresh start and let all these guys move on from bullying,” Straten said.

Things were easier for Matthew after he left school, even though the same old bullies lurked around when he attended school sports activities. In one instance, a student followed Matthew from the bleachers to concession stand, despite a school protective order forbidding contact between the two.

Matthew chose to leave the event to avoid further harassment.

Coming out online

Matthew moved on, leaving the situation behind. But, Straten said, “Summer got lonely. We wanted to make sure he had the best possible start to the school year back at Chisholm Trail” when the school began this past August.

But the new school year brought with it the same old patterns of harassment for Matthew, who joined the wrestling team with his brother. On the mat, the same bullies would hold him down, whispering vulgar suggestions in his ear. In the locker room, his teammates wouldn’t let him shower after practice.

Very quickly, Matthew needed a break from the taunts.

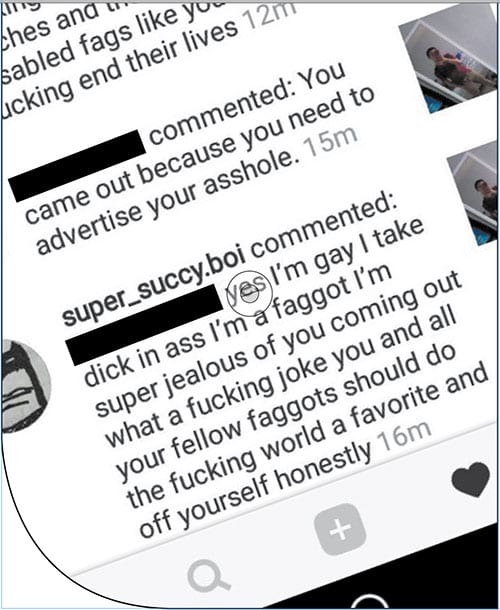

The family took a camping trip, hoping to escape the noise of school and work for the weekend. After texting with a romantic interest throughout the weekend, Matthew decided to come out on Instagram that Sunday. What he didn’t expect was the barrage of hate that began erupting from his phone as Instagram notifications lit up the screen:

“Suck, suck, choke, choke. Oh yes, put it in my … .”

“No one cares, go kill yourself.”

“I wish we were in the 1980s so I could beat the shit out of you to the point of hospitalization without the cops even caring, you fucking loser.”

“I didn’t know dick sucking makes you athletic.”

It never stopped.

It’s easy to discount the impact of social media. But for someone, especially a teenager, already under attack, this digitally-connected world can be much more than tiresome. Imagine facing a barrage of notifications signaling such hatefulness — when you wake up, when you get out of the shower, right before a mid-term exam, when you’re at the dinner table.

That’s what Matthew faced, while he was away on camping trip and after he returned to school. This time, it was administrators at Chisholm Trail High that contacted Straten, notifying her that her son was the victim of extreme cyber-bullying.

Fort Worth Police began investigating the cyber-bullying case, as well as the past harassment. And on Aug. 21, police arrested three juveniles in connection with the case, according to Fort Worth Police spokesman Sgt. Chris Britt. Neither police nor officials with the Tarrant County Juvenile Court could disclose details of the charges or any prosecution because the suspects are minors. One of the three transferred to a different school after the arrests, but the other two remain at Chisholm Trail High, according to Matthew and his brother.

Neither officials at Chisholm Trail High School nor at Eagle Mountain-Saginaw ISD had responded to a request for comment by press time.

Understanding the laws

Straten points to a variety of laws and statutes already in place to protect students from such bullying and sexual harassment. But, she said, the school has chosen to protect the alleged bullies at her son’s expense.

In Texas, David’s Law provides specific definitions and guidelines for dealing with bullying at school. The law, which took effect Sept. 1, 2017, includes offenses related to cyber-bullying and sexual assault, both on and off campus. The law was added to the Texas Education Code, authorizing school districts to take action against bullies.

“David’s Law gives [school administrators] a lot of tools they can use, but there are so many failures,” Straten said.

But application of the law is still unchartered territory for many Texas school districts. It’s hard to find a case where David’s Law has been used to resolve extreme bullying incidents two years after the law took effect. And while the law authorizes school districts to take action, the language in the bill doesn’t require schools to remove bullies or take other such action.

Still, schools are required to take certain measures regarding cyber-bullying, including notifying the victim’s parents.

Meanwhile, the Texas Penal Code also defines harassment as a punishable offense. Section 42.07 of the Texas Penal Code spells out harassment as the “intent to harass, annoy, alarm, abuse, torment or embarrass” another person, either with obscene comments, requests, suggestions or proposals; by threatening to “inflict bodily injury on the person” or commit a felony against the person or his or her family or property; by falsely reporting that a specific person has died or been seriously injured; repeatedly making harassing phone calls, and by repeatedly sending harassing or threatening electronic communications.

While she doesn’t believe that the way school officials handled her son’s case, Straten encourages parents and her fellow school resource officers to be on guard against harassment and bullying.

“If you are a parent and have a child going through this at some point, you need to be prepared. It’s been a fight with the school, it’s been an absolute fight. They have no intention of helping,” Straten said. “If I hadn’t had experience knowing the law, knowing the resources and pushing for a charge, then the harassment could have carried on and on.”

……………

Statistics on bullying

• More than one out of every five (20.8 percent) students report being bullied, according to numbers compiled in 2016 by the National Center for Educational Statistics.

• Bullied students reported that bullying occurred in the hallway or stairwell at school (42 percent), inside the classroom (34 percent), in the cafeteria (22 percent), outside on school grounds (19 percent), on the school bus (10 percent), and in the bathroom or locker room (9 percent), also according to the 2016 National Center for Educational Statistics.

• School-based bullying prevention programs decrease bullying by up to 25 percent, according to a 2013 report by McCallion & Feder.

• Students who experience bullying are at increased risk for poor school adjustment, sleep difficulties, anxiety and depression, according to a 2015 report by the Centers for Disease Control.

• The percentage of individuals who have experienced cyberbullying at some point in their lifetimes has nearly doubled — from 18 percent to 34 percent — from 2007 to 2016, according t a 2016 report by Patchin & Hinduja, 2016.

• 74.1 percent of LGBT students were verbally bullied — called names or threatened — in 2012 because of their sexual orientation, and 55.2 percent were verbally bullied because of their gender expression, according to the 2013 National School Climate Survey.

• 36.2 percent of LGBT students were physically bullied — pushed or shoved — in 2012 because of their sexual orientation, and 22.7 percent were physically bullied because of their gender expression, also according to that same National School Climate Survey.

• 49 percent of LGBT students experienced cyberbullying in 2012, according to the National School Climate Survey.

• Only 40–50 percent of cyberbullying targets were aware of the identity of the perpetrator, according to the 2016 report by Patchin & Hinduja.

• An analysis found that students facing peer victimization are 2.2 times more likely to have suicide ideation and 2.6 times more likely to attempt suicide than students not facing victimization, according to a 2014 report by Gini & Espelage.

Information provided by PACER. Founded in 2006, PACER’s National Bullying Prevention Center works to prevent childhood bullying, so that all youth are safe and supported in their schools, communities and online. For more information about bullying prevention and all of PACER’s efforts, visit pacer.org.

“According to Matthew, two students grabbed him and tried to hold him down. He managed to break free. But one of the boys grabbed him from behind and started dry-humping him while another student grabbed his face, telling him, “You looked beautiful today” and calling him “faggot.”

If a gay boy pulled this kind of crap, we would instantly hear about how gay men are all predators, and that this is what being gay is all about, and The Children Must Be Protected.

but “straight boys” doing exactly the same thing? There seems to be a lack of ability for anyone to connect the very obvious dots.

It reminds me of a scene from The Naked Civil Servant. Quentin and his very femmy, obvious friends get approached by a gang of bullies in a café. The bullies start their usual intimidation thing, and quentin says, “You boys better get out of here before someone figures out which one of you is queer”.

It also reminds me of an article that appeared some 45 years ago in a Chicago paper. The “AUTHOR” opined that homosexuality in certain situations, such as prisons, was perfectly understandable, but living a “homosexual lifestyle” was obviously sick and abnormal. My response, which was published, said “I see. for HETEROSEXUALS, homosexuality is perfectly normal. But for actual gay people, it had to be stopped at all costs.”