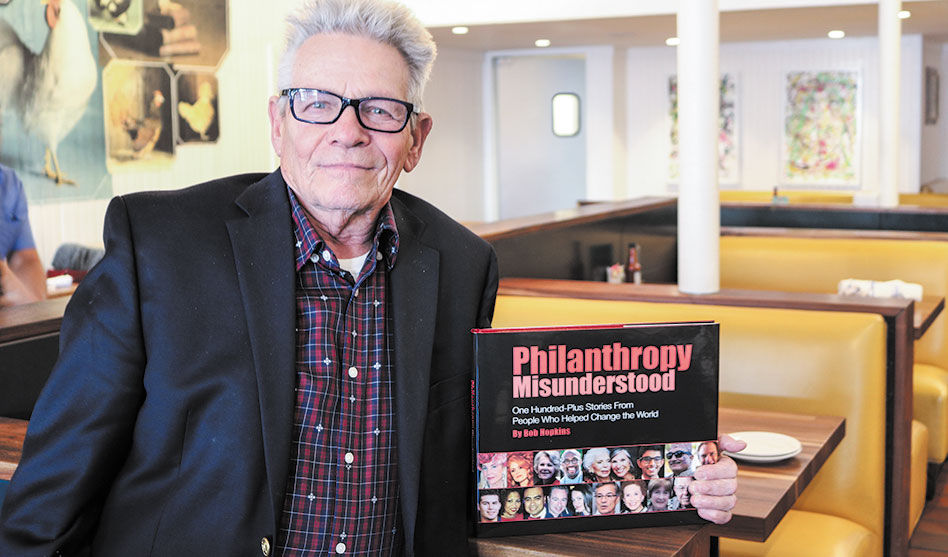

Bob Hopkins believes the universe will tell you how to do good in the world, which has made him Dallas’ evangelist for philanthropy

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

When Bob Hopkins first moved to Dallas in 1984, he was certain his education and training in fundraising would quickly land him a position. But that initial job hunt was surprisingly slow-going.

“Nobody in Dallas would hire me!” he says. “Fundraising is about relationship-building, and that means knowing people, and I didn’t know anyone.”

What a difference a few decades can make. After landing that first job (someone with the Shelton School took a chance on the newcomer), he moved on to fundraising for the Neurofibromatosis Foundation and other positions. For a dozen years, he published the newspaper (later magazine) Philanthropy in Texas, in which he focused on major contributors to charitable causes and organizations. Today, Hopkins is the acknowledged maven of philanthropy.

“Organizations fail all the time because they don’t know how to fundraise,” he says. “You can know people but not have the skills to fundraise.” And while teaching those skills is a huge part of what has driven his career over the years, he is quick to point out that “donating money” and “philanthropy” are not synonymous… though there is a ton of overlap.

“When Rockefeller and Carnegie started building libraries and colleges and such, people needed to call them something other than donors,” to represent their magnanimity, Hopkins points out. “Philanthropist” became the settled-upon term, even though the definition of philanthropy doesn’t necessarily involve money — it’s merely the love of humanity and the promotion of the welfare of others. Its essence concerns the acknowledgment of community and our desire to help out our fellow man in any way we can — a message that seems especially poignant during the current crisis.

And that’s why he titled his book Philanthropy Misunderstood.

“Everyone in this book I have worked with at some point,” he says. And from their examples, he tells more than 100 tales of people both rich and of modest means who have made a difference embracing the principles of altruism and philanthropy.

The process went fairly quickly. The idea for the book came about two years ago, when a friend gave him the confidence to believe he could write it. But the actual writing only took from May to November of last year. He elicited stories from the likes of model-event planner Jan Strimple, jeweler Joe Pacetti, Paul Quinn College president Michael Sorrell and Gayle Halperin with Bruce Wood Dance. But he also includes stories by folks like Andrew Ayala, a recent Eastfield Community College alum, who became inspired by Hopkins to become active in his church group; and Diego Franco, another of Hopkins’ students who went on a trip to Mexico and discovered how helping children in a small town pick up trash could be so transformative for many lives, including his own.

Philanthropy is both easier and harder than you might imagine. The trick is to jump right in. By way of example, Hopkins discusses how a few months ago he was at H&R Block having his taxes worked on when the preparer asked him about his occupation; when he explained it to her, she became excited.

“She said, ‘This weekend is my first time to volunteer for an activity: Taking care of children after school for parents who work.’ She was doing it totally free of charge,” he says, but was enthusiastic about it. Which is really the secret to philanthropy: “When you find something, you develop a passion for it. And if you don’t know what your passion is… well, pay attention to the world around you, and the opportunities will come to you. Hold out your arms and say, ‘God, here I am — come and get me!’ It’s addictive.”

“Addictive” is an interesting choice of words, since Hopkins himself traces his involvement in philanthropy back to 1980 when he entered Alcoholics Anonymous. He believed strongly in the program and wanted to help out others suffering from dependency. That led him down a path devoting his skill-set to doing good in the world. (Another upside?

Hopkins met his partner of 40 years at one of those AA meetings.)

Of course, once you begin to give — of your time, of your ideas, of your passion — your enthusiasm becomes contagious. That leads others to share in your enthusiasm and, hopefully, give as well (hence the fundraising component). “People who don’t give often question the purpose of [philanthropy],” Hopkins says. It’s a sort of variation on the “teach a man to fish” axiom.

Amazingly, Hopkins notes that even still, individuals are the driving force in giving.

“The least giving as a percentage is done by corporations, then foundations — most comes from people,” he says. “No. 1 is church; no. 2 is education; third is health; fourth is social services — including things like parks. No. 5 is the arts, followed only by ecology,” which nobody even gave to until recently, he says.

And remember: You may need to pick your lane and stick with it, especially if you want to make a difference long-term (and stay committed to your goal). Hopkins notes that many of North Texas’ most notable philanthropists — those with names like McDermott, Meadows, Nasher, Hamon, Perot — are often associated with specific causes: the arts, health research, education, civic projects. Even they have their priorities.

The bad news is that Texans, despite their braggadocio for doing everything bigger, tend to lag behind the national average in the amount of charitable giving as a portion of income (under five percent). The good news is that the trends have always gone up.

“No matter what the climate of the economy, every year since they started keeping track, giving has grown. We’ve never had a fallback because of a disaster or economic downturn — that’s more than 50 years,” Hopkins says. And while the current shelter-in-place restrictions may curb activity for a while, the best way to keep the trend going is to start with yourself.