DTC’s ‘Hair’ threads the heroin needle in an immersive, dazzling production

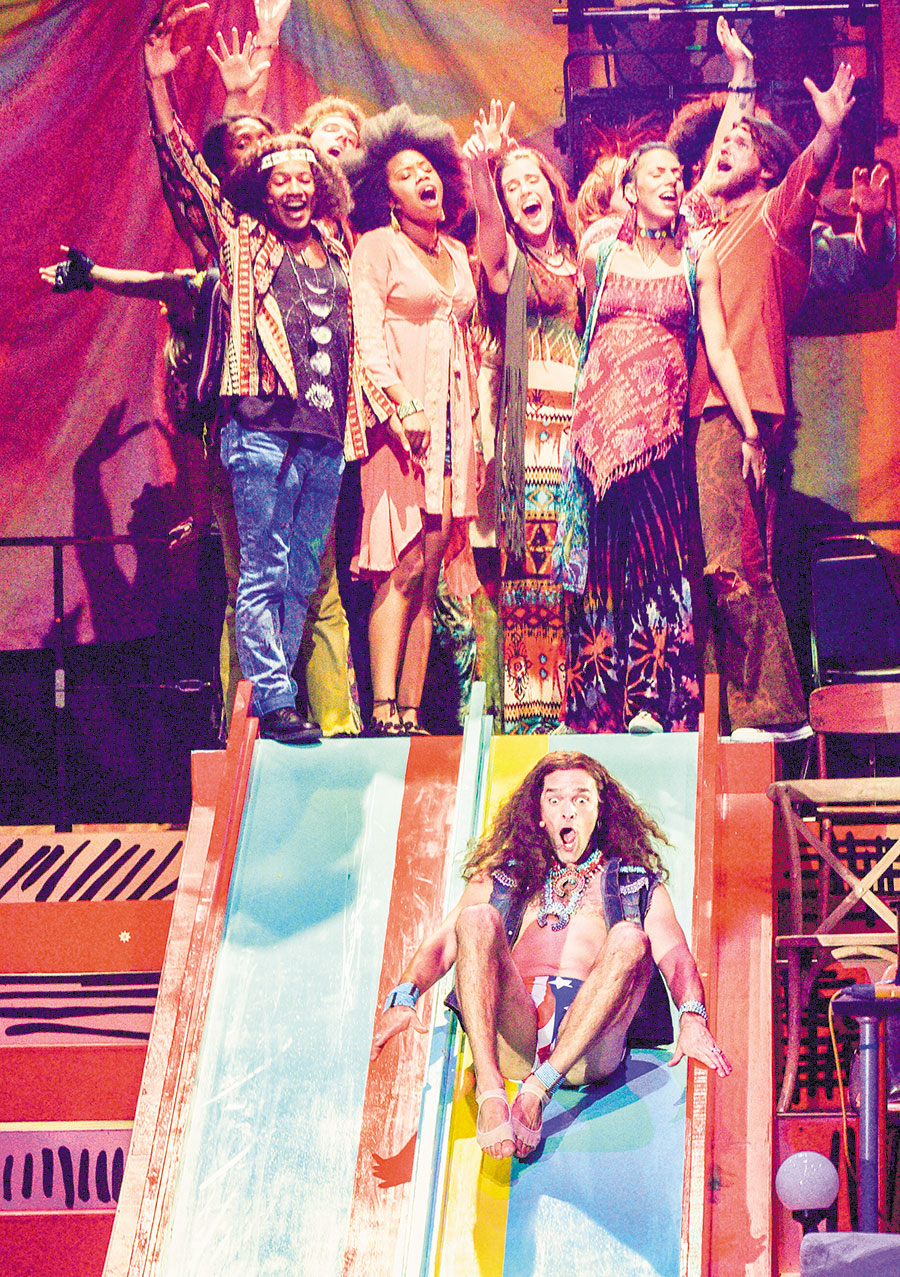

The circus-like atmosphere of ‘Hair’ manages to be joyous but never condescending. (Photo by Karen Almond)

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

When the original production of Hair debuted on Broadway nearly 50 years ago, the actors populating the cast weren’t faking the counterculture — they were living it. The show was as contemporary as a book-musical can be: The Summer of Love wasn’t even a year past, and the librettists/stars were practicing what they preached: Anti-war sentiment, sexual freedom, recreational drug use and defying the conventions of their squarents. They might as well have been singing the headlines of the New York Times. It was iconic.

When the original production of Hair debuted on Broadway nearly 50 years ago, the actors populating the cast weren’t faking the counterculture — they were living it. The show was as contemporary as a book-musical can be: The Summer of Love wasn’t even a year past, and the librettists/stars were practicing what they preached: Anti-war sentiment, sexual freedom, recreational drug use and defying the conventions of their squarents. They might as well have been singing the headlines of the New York Times. It was iconic.By the time the film version opened in 1979, the Vietnam War was over (and had been lost), and hippies had given way to Reagan Republicans. It was an anachronism, a period piece. The music might endure, but the message seemed naïve, retro.

And on each subsequent version, my concern has been the same: If the folks making the musical think of the revolution of the 1960s with the same remote quaintness as the Old West or the Jazz Age, you get Annie with beads and headbands. The temptation to commoditize counterculture, to diminish the passion of the protest (“Keep Calm And Smoke Weed”) lurks in every revival.

And for a few moments in the DTC’s production, that feeling began to seep in. You enter the Wyly Theatre space and it has been transformed. The uncomfortable green torture devices known as their standard seats have been replaced by couches and recliners. The balconies are now tiered performance spaces. In the center, a whole in the stage houses a band all dressed in dashikis and bell-bottoms while the actors roam for a pre-overture “Happening,” getting audiences members to tune in, turn on and drop out. Will this become a circus, where the clowns are besandaled junkies … or worse, faux-junkies?

Not. At. All.

It doesn’t take long for you to groove to the vibe, man. Yes, there is a circus atmosphere, but it’s not a side-show, instead in service to the fun and humanity (and in contrast to the serious turn the story takes at the end). Director Kevin Moriarty, who seems psychopathic in his desire to “reinvent” theater with each production — sometimes successfully (Electra), sometimes disastrously (Inherit the Wind) — has threaded the heroin needle. This Hair never condescends but flows like the tresses on a Breck Girl. It’s exciting, energetic, dazzling. More than with almost any show Moriarty has directed, he achieves that most elusive goal of modern theater: To form a real community, if just for a few hours.

There’s not much of a plot here. In many ways, Hair prefigured The Rocky Horror Show while looking back to vaudeville — it’s like the stage-musical manifestation of the Sgt. Pepper’s album, from the hodge-podge costumes to the rangy song choices. Loosely, best friends Berger (Chris Peluso) and Claude (Jaime Cepero) live a free-wheeling existence in NYC’s West Village, getting stoned, sleeping around, trying on new personalities (Claude affects a British accent, though he’s a middle-class kid from Queens). They plan to burn their draft cards and show their contempt for the Establishment, but Claude’s inherent bourgeois upbringing stands in the way of truly breaking free from society, with predictable consequences.

The cast of two dozen (including the band, who are part of the action) are more like athletes through the space, which is pretty apparent during the famous nude scene that ends Act 1. Sometimes, it’s played like The Full Monty — a coy “moment” of freedom. Here, it’s slow striptease of sorts, not erotic so much as sensual and freeing. It really captures the essence the era, even for those of us who did not live (and die) through it.

Over at Theatre 3, a very different musical deals similarly with matters of humanity. Adding Machine: A Musical is a recent adaptation of Elmer Rice’s prescient 1923 play, in which a lowly office worker (Thomas Ward) with 25 years at his company finds himself replaced by a dull piece of technology, and exacts his frustration on his boss. Rice was writing during an era when the industrial revolution had led to renewed interest in the role of mankind in the world; the Russian Revolution just a few years earlier was a “workers’ rebellion,” and one’s soul was largely tied up in a man’s (and perhaps a woman’s) ability to participate meaningfully in society. (The theme would be revisited in the 1950s in works like Death of a Salesman and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit.)

Over at Theatre 3, a very different musical deals similarly with matters of humanity. Adding Machine: A Musical is a recent adaptation of Elmer Rice’s prescient 1923 play, in which a lowly office worker (Thomas Ward) with 25 years at his company finds himself replaced by a dull piece of technology, and exacts his frustration on his boss. Rice was writing during an era when the industrial revolution had led to renewed interest in the role of mankind in the world; the Russian Revolution just a few years earlier was a “workers’ rebellion,” and one’s soul was largely tied up in a man’s (and perhaps a woman’s) ability to participate meaningfully in society. (The theme would be revisited in the 1950s in works like Death of a Salesman and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit.)Adding Machine strikes me as of a piece with two other works of its era: Maurine Dallas Watkins’ 1926 Chicago and Joseph Moncure March’s 1928 poem The Wild Party, both of which were made into musicals: They all prefigure the “Well, it was good while it lasted” malaise of modernity, and the psychological costs of living in it. (You could add The Great Gatsby, An American Tragedy and the film The Crowd to that list, and others as you see fit.) And the production of this 2008 musical, staged with intelligence and an appreciation for its structure as a virtual chamber opera by director Blake Hackler, fearlessly delves into the psychology with a number of daring details. For once, the “hero,” Mr. Zero, is hardly heroic, but a selfish bigot; his wife is a shrew; his boss heartless; his cellmate a sociopath. In short, there are not many likable characters here.

But that seems as it should be. Though set nearly a century ago and written a decade ago, something about it taps into the Angry White Man ethos of the Trump Era. You might not sympathize, or even empathize, but you begin to understand. The music, largely discordant and modernist, is nonetheless evocative, and while the script veers wildly into fantasy, spirituality and satire, it never loses its thrust. It’s certainly one of the most unusual musicals of its kind, but undeniably provocative.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition October 6, 2017.