Three deaf gay North Texans refuse to let what some would see as a disability stand in the way of a fulfilling life

RICH LOPEZ | Staff Writer

lopez@ dallasvoice.com

Noise. There are layers of it every day. The bustle of traffic, dogs barking, someone stomping down the hall, the whirring of a desk fan and the blare of digital music from computer speakers.

These can all register with most people all at once — even if they don’t know it. For some others, they may be fading aural glimpses — or nothing at all.

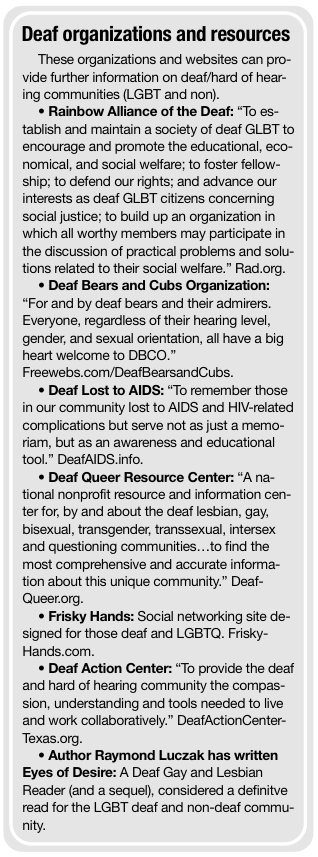

When deaf culture and gay culture collide, it’s not an unusual thing. Although one has nothing to do with the other, there is an interestingly significant proportion of gay people who are deaf. The Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf states that the percentage of the LGBT population is “approximately 10 percent of the deaf population.”

But is there an added pressure to being deaf or hard of hearing and gay?

Three gentlemen would say no.

“The deaf community is a very welcoming one and doesn’t discriminate,” Jeffrey Payne says. “It’s a non-issue.”

Payne may be most recognizable as the winner of International Mr. Leather in 2009 and more recently as a new co-owner of the Dallas Eagle club — but more on him later.

Born this way

Speaking of non-issues, Andy Will was born completely deaf 36 years ago. He seems perplexed at times talking about it, because for him it’s a fact of life. And knowing he was gay at a very young age didn’t hurt Will in discovering who he is.

“I knew I was gay when I was 8,” he said.

For the record, the majority of his quotes here are via Facebook chat and text messages.

Will didn’t come out until later, and before doing so he got married and had a daughter, Sarah. The gay thing didn’t go over too well with his wife, and the two were only married for eight months. Will didn’t see Sarah for quite some time.

But something in Will is so optimistic about life and what it offers that it would seem patience paid off for him. Or maybe it’s optimism mistaken for proud parent considering the exclamation he has when talking about his girl.

“I wanted to be honest to my family and my ex-wife that I’m gay,” he said. “I didn’t see my daughter for 11 years but she came to see me on her 12th birthday and we’re happily back together. Father and daughter! And she knows and has kindly accepted me as being her gay dad!”

“I wanted to be honest to my family and my ex-wife that I’m gay,” he said. “I didn’t see my daughter for 11 years but she came to see me on her 12th birthday and we’re happily back together. Father and daughter! And she knows and has kindly accepted me as being her gay dad!”

In the meantime, Will met Joseph and they were together for five years. But Joseph passed away after losing a battle to cancer. Will met Dwane online and then officially at JR.’s Bar & Grill. They are celebrating 10 years together.

Dwane is not deaf.

“I’m not sure how I did that. Life is pretty happy here,” Will said.

Some of Will’s hobbies may seem unexpected to the hearing population. Once a week he drives more than 50 miles from his home in Krugerville, north of Denton, to the Oak Lawn Boxing Gym off of Riverfront Boulevard. He’s been taking lessons from gym owner Travis Glenn for “about four or five months,” and according to the coach, it’s been a learning experience for both men.

“Many people have suggested that I just need to learn a few basic American Sign Language signs, but that doesn’t work when you have on boxing gloves,” Glenn said. “It took a few lessons, but Andy and I have found a working rhythm for his training. When he does something that needs adjustment, I point to him, mimic what he did, and shake my head ‘no.’ Then I point to myself, do the movement correctly, and shake my head ‘yes.’

“I’m sure it looks odd to bystanders, but it seems to work for us,” Glenn said.

Will mentions that sometimes they have to work with a pen and pad or that he can read Glenn’s lips as he speaks, but he’s at the point now where he can almost tell what Glenn is thinking.

“I can read his movements and body language but sometimes I can read what he means in my mind and get the movement right,” he said.

Out of simple ignorance, people may incorrectly assume that deaf people can’t do as much as hearing people. But Will has never bought into that.

“I’ve been playing sports since I was a kid,” he said. “I used to play basketball and football in school and I currently play on softball and rugby teams. And now boxing.”

Again, for Will, this is nothing, but he knows what people may think. He isn’t trying to shatter any images. He’s just living his life. But if he changes someone’s perception along the way, he’s fine with that, too.

Above all the labels that people could place on Will, he’s shooting for one.

“I’m the proud gay dad of Sarah,” he said, “And sometimes I can surprise people that a deaf person can do the things that I like doing.”

Normal fears

Ronnie Fanshier used to be a male dancer. He once was Mr. Texas Leather. Now he lives a comfortable life in the suburbs and is one step away from being completely deaf.

“I am classified as profoundly deaf,” he said.

He also just turned 50 and isn’t worrying so much about his deafness as much as just accepting the landmark birthday — like anyone does.

“Fifty is a milestone if you’re gay, straight or whatever. I have mixed feelings about it, but I appreciate what I’ve learned about life up to this point,” he said. “I certainly would not want to go back and live all over again. There would be so many friendships and loves I’d miss out on and that’s not a chance I would take.”

For someone who is so close to having 100 percent hearing loss, Fanshier doesn’t sound like he’s letting that be an albatross. Born with nerve deafness — meaning that the nerves transmitting sound to the brain don’t function properly — Fanshier always knew what the ultimate result would be with his hearing. Acceptance wasn’t so much an issue, but socially, it did have an impact — good and bad.

“Looking back to school, I adapted quite well to most social situations I was exposed to. I knew I was gay at an early age, but I played the boyfriend/girlfriend game until I graduated. Back then, if you were even suspected of being gay, you were pretty much ostracized,” he said.

“Looking back to school, I adapted quite well to most social situations I was exposed to. I knew I was gay at an early age, but I played the boyfriend/girlfriend game until I graduated. Back then, if you were even suspected of being gay, you were pretty much ostracized,” he said.

As a youth, Fanshier seemed to use his deafness as a way to glide by students prone to bullying anyone who was gay, although he remembers it with some delight.

“Being hard of hearing/deaf helped immensely in that respect, since I was already a little different in an accepted way,” he recalled. “What’s funny is I remember some classmates saying I was a ‘fag’ and other classmates would say, ‘No he’s deaf, and that’s why he talks different.’ Isn’t that a hoot?”

As adulthood came, Fanshier says he kicked the closet door down and hit the gay bars. Everything he had learned socially in school to communicate and even get by worked wonders for him in the community. And he developed his own tricks to party it up on the dance floor.

“I loved dancing,” he said. “I would turn my hearing aids off and dance to the beat. If the bass got soft, I would watch others on the dance floor and use their rhythmic movements to create a sort of metronome to dance to until the bass got strong again.”

He loved it so much that he took it to the pedestals. As a college student, he danced his way through gay bars in Dallas, Houston, Oklahoma City and Tulsa. His confidence brimmed.

“I was young, athletic-looking and very personable,” he said. “I would intentionally wear one hearing aid up there on the box and it was a good ice breaker for tippers. This was another way of making myself more memorable. I was very social and outgoing and my handicap never stopped me.”

What Fanshier does instead is own his deafness. He didn’t apply fear to it and instead worried about what he says every gay man probably worries about: Health, finding Mr. Right (he did), family acceptance — oh, and one more thing:

“Will I be able to get the clothes, car and home that any self-respecting queen should have,” he joked.

What’s curious about Fanshier is that he never learned sign language. He was actually discouraged by his parents and teachers who feared that society would single him out. And he’s glad for that.

“I thank them profusely for that,” he said. “I would not be the person I am today if that decision had not been made for me. I should learn ASL, but I tend to have a short-term memory and I probably wouldn’t retain it, and I have few hard-of-hearing friends to use it with. I also work in a mainstream environment, and sign language would have severely limited my job options.”

But Franshier’s made it work the way he knows how. He’s built a good life with a long tenure at the hospital he works for, a house by the lake and his partner of 14 years — all while taking what may easily be considered a detriment, and turning it to his advantage.

The emergence of a voice

Jeffrey Payne has not been silent about his experience. He told the Voice before about discovering his hearing loss at 40 years old and was initially told he would be completely deaf by Christmas 2010.

The timeline has been wrong so far, but Payne has taken his visibility in the Dallas LGBT community and is turning it into increasing the awareness of Dallas gay deaf denizens.

“I’ve come to know many individuals in Dallas who are hard of hearing and also gay,” he said. “What’s really wonderful about it is that it’s all part of same gay community.”

Payne himself could be looked upon as the spark that began an increased interest in Dallas. With such a high profile in the leather community that reached out beyond, people could identify with him in a way perhaps they couldn’t before.

“I believe some people saw the need for it when I went from hearing to hard of hearing,” he said.

He’s worked with several local gay organizations in increasing options for hard of hearing, but was ecstatic with the Texas Bear Round Up’s efforts this past March.

Organizers looked to Payne for directon on providing an enjoyable experience for hard-of-hearing and deaf bears attending.

“With TBRU, this huge event and largest bear event I believe, they were so proactive reaching out to me and the St. Cyr Fund to ensure interpreters at all functions,” he said. “I was thrilled, to be honest with you.”

The Sharon St. Cyr Fund was created by Payne — and named after his mother — to assist with purchasing hearing aids for those who can’t afford them and to increase the presence of ASL interpreters at events. Payne has taken his plight and turned it into opportunity — and doesn’t mind if he’s a little uncomfortable.

“Just with my story I’ve been given, I’ll talk to anyone on a microphone, even if it is out of my comfort zone,” he said. “ASL is really just a different language, but some people get frustrated if they can’t sign. [Hearing] people also want to learn so it’s nice knowing the awareness level is there now. Sign language is a very beautiful language.”

As for his personal struggle, Payne doesn’t dwell on it. He sounds repurposed for this new mission in life. He credits his husband, David, and his family for their support and understanding. He’s intent on not just dealing with deafness, but making the most of it.

Payne said before winning IML, he was a background kind of guy. That ended when his name was announced as the winner, but he was encouraged by his partner not to waste the opportunity he had.

“I’ve always been a firm believer that things happen for a reason,” Payne said. “I was thrust out of the background with IML and now I can make a difference.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 15, 2011.

Thank you to RIch and the Dallas Voice for covering this topic and being so supportive of our community! Your continued support has helped so many individuals, and I can’t thank you enough!

One Note: My husband’s name is David (not William) and has been my husband for the last five years and continues to be my husband. Thanks for the laugh though, as David and were wondering when “William” was going to start contributing to the household fund! LOL

But again, thank you Rich for an incredible story and supporting us!

Jeffrey Payne

This is an awesome, inspiring piece. Thanks for taking the time to bring it to us!

This article I happened upon it by mistake. I was looking for an article for my core class, and since I am gay as well as being deaf since birth this caught my eye right away. I enjoyed learning a little About the three men. Congradulations for them in accomplishing what they wanted out of life.

Great article! Thanks for publishing it. My deafness came thanks to my Army career. Hearing aids were my retirement present from the Army. I can empathize with all three of these men. Some part of each of their lives is similar to mine. I love my hearing aids and don’t like to be without them. I even carry a packet of spare batteries with me when I leave home. However, they amplify everything, and I never was able to convince my ex-wife that her voice was not the only thing amplified, and she needed to be sure she had my attention before speaking to me. LOL.

The level of courage that these three men possess cannot be described in words nor measured in decibels. Ronnie, glad to see you are doing well. It’s been a while.

Great article, Rich Lopez.

I read the article and there he was. Ronnie. Although he will not remember me I remember him dancing. I’m happy to see he is doing well.

You might also be interested to know that International Deaf Leather was ‘born’ in Dallas, TX during Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf 1991 conference at Wydham Hotel. Big Hello …. Kudos … and Hugs to Jeffrey Payne and Ron Fanshier (sorry I’ve not met you yet, Andy …. woof)!

Philip Rubin, International Mr. Deaf Leather 1991 (used to live in Dallas, TX too …. good ol’ days!)

My pleasure is to know those three guys have accomplished so well after years of identity struggle and/or uncertainty. A good role model for deaf LGBT and we all ought to be a person of “grand” success regardless of sexual orientation. Things are better for us now than several decades ago. I want to emphasize that each person is no one else’s but his / her own master (“le maitre chez soi”). Let deaf GLBT community continue to grow and become world-wide visible —

These deaf gay men demonstrate that Dallas is a cultural magnet for creative individuals.

For decades, deaf people from across the country found their way to Dallas and enlivened the community around them. Sometimes they move on to other cities, but Dallas – especially its gay community – remains an incubator for innovation.

Marc …. is that you??? Michael Felts? A ghost from the past …. LOL You were (and probably still are) very much part of what was happening in Dallas!