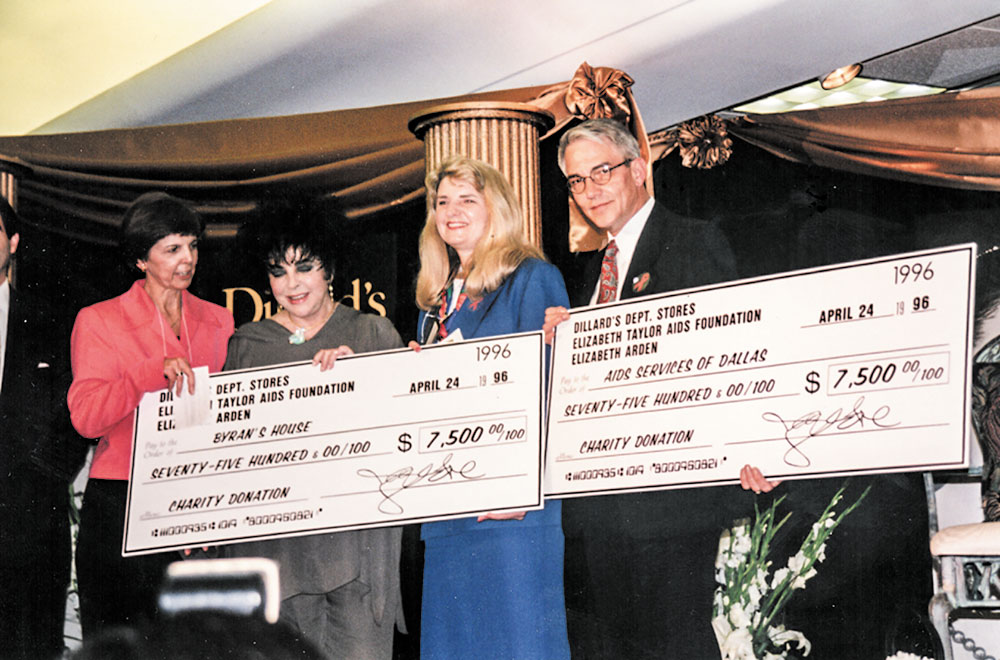

Don Maison said that the above photo was his favorite out of so many photos taken of him.

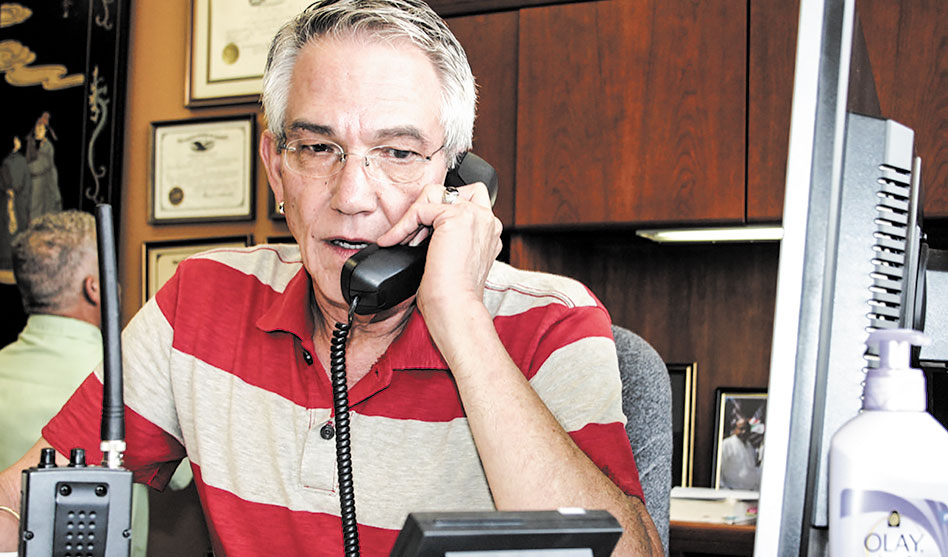

Don Maison took care of housing needs for people with HIV and defended LGBTQ people against discrimination

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

When Don Maison retired as president and CEO of AIDS Services Dallas in 2019, after 32 years at the organization’s helm, he was the longest-serving head of an AIDS organization in the United States. He died on Feb. 21, just three years after retiring, following a long illness and a short battle with esophageal cancer.

When Maison retired, Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price presented him with a proclamation, joking that he wasn’t sure if Maison, who was an attorney as well as HIV/AIDS activist and agency head, was being courageous when he took on the often-embattled Price as a legal client, or if Maison was just a little crazy.

Before dedicating his career to housing people living with HIV, Maison was an attorney fighting for LGBTQ rights, and he was responsible for leading the legal effort to end police harassment in LGBTQ bars in Dallas.

Then in the late 1980s, at the height of the AIDS crisis, Maison was hired to become the new executive director of what was then known as the PWA (People With AIDS) Coalition. PWA Coalition became AIDS Services of Dallas not long after Maison took over.

While the young organization had dabbled in several areas of AIDS care, Maison found ASD was best at providing housing. So ASD decided to leave testing, education, counseling and other services to Oak Lawn Community Services and other HIV agencies and instead concentrated on their own specialty.

Maison accepts a check from Elizabeth Taylor.

Maison was one of the original members of the National AIDS Housing Coalition. Within a few years of changing its focus, ASD became a national leader in providing housing for people with HIV, and Maison established a national reputation. When Elizabeth Taylor created her AIDS foundation, Maison’s facilities were an early stop on her national tour and recipient of her largess.

In the rough draft of a 1991 book on AIDS housing around the country, Maison was described as “flamboyant, chain-smoking, irreverent and obnoxious.” He was disappointed when that description was removed from the final version, but he framed the page with the quote from the draft.

Current ASD staff members laugh at that description of him, describing the man they knew as personable, passionate, supportive, happy-go-lucky, well-respected and loved.

Kathie Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama. remembers Maison as a prankster, the man who put an app on her phone that made a fart noise. During a meeting of the National AIDS Housing Coalition, the app went off and Hiers couldn’t get it to stop.

But when it came to housing persons living with HIV, Maison was serious, and he was relentless.

After ASD had acquired and renovated Ewing House, its first facility for those with HIV, protesters greeted the facility’s opening with signs that read “No gay/AIDS colonies.” Area residents, afraid a house for persons living with AIDS would bring down values in this impoverished neighborhood, were fueled by homophobia and AIDS-phobia.

Instead, because of the impeccable job ASD had done turning an eyesore into a showplace, area property values soared.

Rather than deterring him, the protests targeting him and his agency just invigorated Maison and encouraged him to purchase Revlon and Hillcrest houses. Work on Revlon House was interrupted by an arson fire. But by this time, Maison’s reputation for providing housing preceded him, and Dallas Housing Authority and then-state Sen. Eddie Bernice Johnson stepped in and helped get Maison’s agency on firm footing.

A fourth facility, Spencer Gardens, marked a new milestone in ASD’s — and Maison’s — drive to house persons living with HIV. ASD built that fourth property, designed for families affected by HIV, from the ground up rather than renovating an existing property.

Shortly before his retirement, Maison and his team acquired another small apartment complex, down the street from the other facilities. ASD broke ground on that renovation just weeks before the COVID pandemic hit and everything was locked down. The project was further delayed a year later by a fire that destroyed one of the two buildings and damaged the other.

Work on that property is underway now, and it will become part of Maison’s ASD legacy.

In an interview several years ago, Maison objected to the idea that ASD is — or ever was — a place that people with AIDS went to die. “This was never a sad place,” he declared.

Maison spoke about the ASD residents like a proud parent. He told the story of one who was a truck driver who, he became positive, lost his job and his home then moved into an ASD residence. Thanks to advances in medications and treatments for HIV/AIDS, “He got stable with his meds and got his CDL back,” Maison said at the time. “He got his own apartment, and he just bought his own rig.”

But it isn’t just people with HIV who owe Maison big thanks. Anyone who has ever been to a gay bar in Dallas without having to deal with police harassment can thank Maison for that, too.

In 1979 police raided Village Station (a bar then located at the corner of Throckmorton and Cedar Springs in the building now occupied by Roy G’s and Skivvies, and which over time evolved into S4) and arrested a number of men for lewd conduct. The charge? The men had touched each other while dancing.

The cases actually went to court, and, during the trial, one of the officers claimed to the Dallas Times Herald he loved busting gays because he had them “over a barrel.” But as it turned out, he didn’t.

During the trial, the arresting officers gave testimony claiming that from where they were standing, near the bar’s entrance, they had seen men touching on the dance floor. So Maison asked for a recess and had someone run down to the office of Caven Enterprises — which owned Village Station — to pick up a copy of the bar’s floor plan. Then that afternoon when the trial resumed, Maison showed the judge that the officers couldn’t be telling the truth because from where they had been standing, they could not possibly have seen the dance floor.

Since the officers were obviously lying, the cases were dismissed. And in true Maison style, after that case he bragged he had become “board certified in public lewdness.”

While police harassment in the bars didn’t completely stop as a result of that case, it was a turning point.

And in another Maison coup for the LGBTQ community and beyond, Maison led the lawsuit guaranteeing that male flight attendants and ticket agents were hired by Southwest Airlines.

That case started when Gregory Wilson applied for a job at Southwest but was told he was “the wrong sex” to work for that airline. Wilson went to Maison, and Maison asked another attorney — Ken Molberg, now a judge on the Fifth District Court of Appeals — to join his “team.” They filed Wilson v. Southwest Airlines, a class action employment lawsuit.

During the first day in court, Southwest repeatedly called its employees “stewardesses” — until Judge Patrick Higginbotham ordered, “You will refer to them as flight attendants in my court.”

That case dragged on for years, but Maison finally won, even seeing that victory upheld on appeal. And Southwest began hiring male flight attendants and ticket agents.

For the residents of ASD’s properties, Maison left the agency in good hands. Current CEO Traswell Livingston had years of housing experience even before he joined ASD 10 years ago.

What residents and staff have lost is a friend: Maison usually ate his lunches in a cafeteria at ASD, alongside the residents. He would always talk to each person on either side of the serving line — resident or staff — about something going on in their life. He was always involved with and interested in each person working or living at ASD. And his friends there will miss him greatly.

But there will be reminders of him all around the ASD neighborhood: To honor Maison and his contribution to the city, the Dallas City Council has decided to put “Don Maison” sign-toppers — like those that mark neighborhoods — on the corner signs near Ewing House.

Don is an amazing human!

Dear David,

Thanks for the excellent article on Don Maison. There wasn’t an iota of exaggeration in what you wrote. He lunched daily with residents. He KNEW them. Assisted them. I had the honor of knowing him for only 25 years. My loss. His passing is a major loss to the community. Love to you Don ❤

Don was a great guy. I often sat and had afternoon cocktails with him in JRs and he’d help me with the NY Times crossword. That was the early 90s and seems like a lifetime ago. He was funny and just fun to be around. I’m sorry to hear of his passing.

As a fellow executive director, I have so much admiration for the work that Don Maison was able to accomplish. He was a fighter for people and his legacy will not be forgotten as he affected the lives of so many people. He fought for the little guy and for the basic human need for housing. ASD is a haven for all who live there.

Don, I will miss our laughs and will fondly remember all the work we did together. You will be missed.