A new album, a new memoir — a chat with half of the queer twin duo

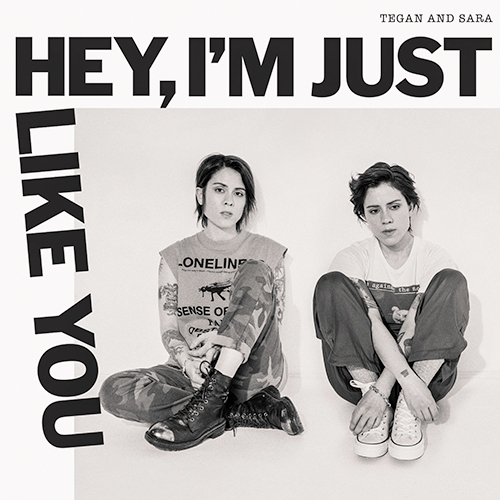

Tegan and Sara’s ninth studio album, Hey I’m Just Like You (Warner Records) came to be in a fascinating way. While doing research for their just released memoir High School, they discovered previously lost cassette tapes of early songs that they rerecorded for the new album. These songs, in combination with the memoir, present a fully fleshed out portrait of Tegan and Sara and function as much as autobiography as they do as art. As revelatory as anything they’d previously done, including the challenges of being a twin (“We carried each other’s wins and losses, fair or not”), the book and album pairing are each well worth exploring for fans and newcomers alike. I spoke with Tegan about the book and the album shortly before the twin duo embarked on their current multi-city concert tour.

— Gregg Shapiro

Dallas Voice: why was now the right time for you and Sara to write your memoir High School? Tegan Quin: I think it’s been enough time. I think I can bear looking back at these photos [laughs]. People are always asking to hear about the beginning of our career, and that was sincerely when it started. It also felt like that was an era people are interested in hearing out. We had to start there. Because our career started in the ’90s, it wasn’t documented in the way things are documented now because of the internet and social media. It felt like a great era to mine for stories and revelations. It felt like something our fans would attach to because they hadn’t heard much about it. Also, queer stories aren’t told enough. Queer female stories are even less likely to be told. There isn’t a ton of music memoirs or memoirs about being queer with women at the forefront. Sara and I felt like we had the opportunity. People are interested. We should take advantage.

Dallas Voice: why was now the right time for you and Sara to write your memoir High School? Tegan Quin: I think it’s been enough time. I think I can bear looking back at these photos [laughs]. People are always asking to hear about the beginning of our career, and that was sincerely when it started. It also felt like that was an era people are interested in hearing out. We had to start there. Because our career started in the ’90s, it wasn’t documented in the way things are documented now because of the internet and social media. It felt like a great era to mine for stories and revelations. It felt like something our fans would attach to because they hadn’t heard much about it. Also, queer stories aren’t told enough. Queer female stories are even less likely to be told. There isn’t a ton of music memoirs or memoirs about being queer with women at the forefront. Sara and I felt like we had the opportunity. People are interested. We should take advantage.

Were you or are you journal and diary keepers, and if so, is that how you were able to construct the book? Yes, we were journal and diary keepers. I have to admit that most of the journals were swapped back and forth. My best friend Alex [is] in the book, she and I spent two years passing a journal back and forth because we didn’t go to the same high school. Generously, our friends donated all of these notes and letters and journals and books that we had all shared. We were [then] able to pull a lot of the dialogue, a lot of the emotional milestones that happened. Some of our first relationships and some of the heavier moments were pulled right from those pages. We’re also still friends with most of the people that we wrote about in the book. We had the opportunity to interview with them. I had almost 20 hours of interview time with a lot of the main characters. I was able to use their perspectives and not just write from memory. And we had 25 hours of VHS footage. I think we were able to totally capture our voices and personalities in a way that, had we not documented, would have been harder. We have stayed in touch with all these people. It wasn’t like, “I’m going to go back and write about high school.” I vaguely remember that time. We’ve been talking about it as friends [laughs] for two decades. It was a topic we care about. It was an era that [laughs] we still talk about a lot. For a lot of people, high school wasn’t that memorable. It was memorable for us because it was when we figured out we were gay. It was also when we figured out we were artists and creatives and we started our band. It was a memorable time for us.

Were you at all concerned about your parents’ reactions to some of the revelations about drug use and sexual exploration and such? I wouldn’t use the word concerned, but we were definitely respectful about what we shared and didn’t share. There’s a lot that didn’t make the book just out of courtesy. We always tried to keep in the forefront of our minds that we were telling our story, not someone else’s story. We wanted to address the fact that my mom and Bruce [their mother’s partner, whom Tegan and Sara referred to as their stepdad] separated at the end of high school, but we didn’t want to get into the reasons why. We wanted to talk about the fact that we had done a lot of drugs, but we wanted to acknowledge that my mother had been a single parent and then Bruce moved in with us and my mother went back [to school] to get her master’s and had to work evenings. It wasn’t like we were doing drugs under her nose because we were dicks. She worked hard and did the best she could. We tried to be respectful, but right from the beginning we said it was an important story to tell. We felt like it would be purposeful in that it would touch and effect people and provide representation for a community of people who don’t often have it. In general, I think everyone is glad we did it and, in general, understood why we wanted to do it [laughs]. I think there were some tears, for sure. It’s hard to go back to that time for everybody.

One of the things you wrote about was the sensation of writing one of your first songs, “I felt a glow of purpose.” Do you still feel that way when you are writing songs? Yes. I think I do feel that way. I don’t know if I feel when I’m writing the song, but I feel it when I’m able to record it and demo it, listen back to it and share it. I still get a kick and a high from writing. I think being a creative is still the best part of my job. My career is many jobs. I’m a creator, I’m an influencer, I’m a content creator, I’m a musician, I’m a businesswoman, I’m a merchandise company. I feel like I wear many hats. I do think being a proper creative, sitting down and writing music, is the best part of what I do. I don’t know if I still feel the joy that I felt as a young person. But I do think that going back and listening to those songs, and now rehearsing them and preparing them for this record and for playing them live, I am getting a bit of that same joy. There’s something powerful about singing songs from that era because they’re so raw, direct and honest. I’m certainly trying to tap back into that joy [laughs].

One of the things you wrote about was the sensation of writing one of your first songs, “I felt a glow of purpose.” Do you still feel that way when you are writing songs? Yes. I think I do feel that way. I don’t know if I feel when I’m writing the song, but I feel it when I’m able to record it and demo it, listen back to it and share it. I still get a kick and a high from writing. I think being a creative is still the best part of my job. My career is many jobs. I’m a creator, I’m an influencer, I’m a content creator, I’m a musician, I’m a businesswoman, I’m a merchandise company. I feel like I wear many hats. I do think being a proper creative, sitting down and writing music, is the best part of what I do. I don’t know if I still feel the joy that I felt as a young person. But I do think that going back and listening to those songs, and now rehearsing them and preparing them for this record and for playing them live, I am getting a bit of that same joy. There’s something powerful about singing songs from that era because they’re so raw, direct and honest. I’m certainly trying to tap back into that joy [laughs].

I’m glad you mentioned the multiple things that you are and how you referred to it as many jobs. In your section of the epilogue, you wrote about convincing your grandfather to lend you the money to make your first album by telling him you weren’t “just going to be artists,” you “were going to be business owners.” Does that have anything to do with the title of the 2000 Tegan and Sara album This Business of Art? Yes, because it was not cool to be into the business. We had our hands slapped a lot during that time. We had had management for a very short period. We decided that it wasn’t the right relationship. We were unrepresented when we signed a record deal. We went on to manage ourselves for two years and build our career on our own. There were a lot of people in the industry who said we should focus on the creative and not the business. I thought that was ridiculous. I’m not saying that people were trying to take advantage of us, but we were young women. That time period, pre-social media, pre-influencers, you were supposed to keep them separate, not be involved in the business side. As an artist, you shouldn’t care. It was uncool to think of yourself as marketing as well as being an artist. For me and Sara, that felt emphatically incorrect. If I care about art, I should care about the business. It’s my art, it’s my songs. I should be the one to decide where it goes, what it looks like, what venues I play. If I can’t tell you what my record deal contains, then I’m just an idiot. We must know everything. This Business of Art was a cheeky F U to the industry saying, “We know what’s up. We’re in control and we’re not going to be manipulated.”

Something I found fascinating was the influence of Smashing Pumpkins on you and Sara. Have you met Billy Corgan and does he know the impact he had on your lives? It’s a funny story. We have met Billy Corgan. We were 24 and out promoting So Jealous. “Walking With a Ghost” was climbing the charts on alternative radio. It was our first time ever experiencing any mainstream attention. Elliott Roberts, who signed us, who was Neil Young’s manager and sadly passed away recently, was briefly managing Billy Corgan. It was Billy Corgan’s birthday and Elliott called the hotel where we were staying in Chicago and said, “They’re having a birthday party for Billy. I’m trying to get you an opening slot on a tour of his. He’s aware of you and he loves the song. Would you like to come to his birthday party and play the song?” Sara and I were like, “Oh my God, no!” I’m no different at 38 than I was at 24. I’m horrified to meet famous people, especially people that I respect and love. You get so nervous! We were so awkward about it. At the last moment we told everyone on our team that we were going to go by ourselves. We didn’t want to show up with our gear. We’re just going to go and say hi. They were all so mad at us because they thought we were stealing their opportunity to meet Billy. Our drummer was so mad. We get to the party and his tour manager knew who we were. He came over and said he would introduce us to Billy. He took us over and introduced us, saying that Elliott manages us. He said, “Hi.” Like he had no idea who we were or if he did know he didn’t say. We just spiraled. It was cute, I’m sure. We were like [gushing], “Oh my God, we love you so much! We’ve been obsessed with you since the nineties. One time we slept in a parking lot to get tickets to the Melon Collie and the Infinite Sadness Tour. We love you so much! We weren’t sure if we should come. Elliott told us to bring our guitars, but we didn’t want to. We left our band at the hotel. We hope it’s okay if we come back with them.” He just sort of stared at us and then he said, “Oh yeah, Elliott told me who you are. You can come back as long as your band’s not weird.” We told him they aren’t weird and he said it was all right to come back with them. He walked off and we went back to the hotel. We told the band we can’t go back. They were all so mad at us!

While working on High School, you and Sara unearthed lost cassettes of early songs that you then recorded for what would become the Hey I’m Just Like You album. Did you immediately recognize the Tegan of that time or did she feel like someone else to you? [Laughs] I did recognize me. If anything, I think what’s been shocking about this process is how little I feel like I’ve changed. You go back and you think, “Oh my God, how silly or how ridiculous or how different or I’ve become so much better than I was.” The truth is that, Sara and I, because of our queer identity and because we established that we were musicians in high school and started to build our career right away, I think a lot of our identity was developed at that time. That may not necessarily be common. I think a lot of young people find themselves in college or those first few years out of their parents’ house. But I think probably as a product of being left alone a lot, a lot of responsibility was put on our shoulders, understandably. When I go back and see the journals and the videos and I hear the songs, I see a lot of the person that I am today. I’m proud of that. I think we were really advanced for our age and we had to grow up quick. I’m glad we established so much of who we felt we were during that time. I think that helped us get ahead.

While working on High School, you and Sara unearthed lost cassettes of early songs that you then recorded for what would become the Hey I’m Just Like You album. Did you immediately recognize the Tegan of that time or did she feel like someone else to you? [Laughs] I did recognize me. If anything, I think what’s been shocking about this process is how little I feel like I’ve changed. You go back and you think, “Oh my God, how silly or how ridiculous or how different or I’ve become so much better than I was.” The truth is that, Sara and I, because of our queer identity and because we established that we were musicians in high school and started to build our career right away, I think a lot of our identity was developed at that time. That may not necessarily be common. I think a lot of young people find themselves in college or those first few years out of their parents’ house. But I think probably as a product of being left alone a lot, a lot of responsibility was put on our shoulders, understandably. When I go back and see the journals and the videos and I hear the songs, I see a lot of the person that I am today. I’m proud of that. I think we were really advanced for our age and we had to grow up quick. I’m glad we established so much of who we felt we were during that time. I think that helped us get ahead.