Documentary traces last year’s spate of violence against gay men in Dallas

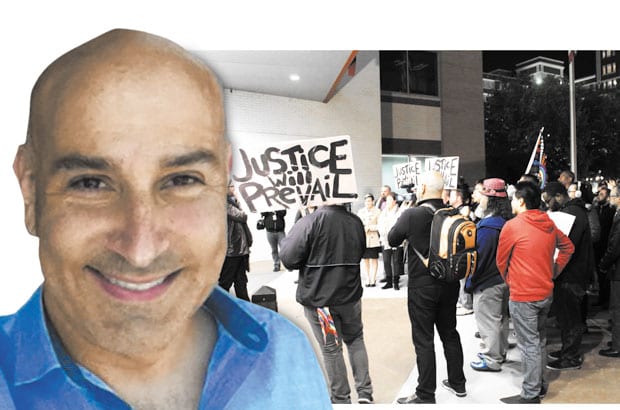

The Light Up Oak Lawn march was one of several that called attention to the attacks in Oak Lawn last fall. (Winston Lackey/Dallas Voice). Below, Steven Pomerantz, with backpack, filming his documentary. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

In October, after hearing about a couple of attacks on gay men in Oak Lawn, Steven Pomerantz decided to attend a rally for the survivors at the Legacy of Love Monument. One of the people he heard speaking there was Michael Dominguez, a survivor of one of the attacks.

“I heard Michael speak,” Pomerantz said. “He was so eloquent. Something clicked in my brain.”

Pomerantz had a video camera with him and decided to start recording. He thought he’d do something creative, maybe make a short documentary about Dominguez and Blake Rasnake, who had been attacked and kidnapped on Pride parade day in September.

Activists held more meetings — with police, with city council members, with Dallas County District Attorney Susan Hawk — as well as a rally at police headquarters and more protests on Cedar Springs Road.

Pomerantz attended them all — and continued filming.

He met a number of people in the community he hadn’t known before: Burke Burnett, survivor of a 2011 hate crime attack who became active last fall, hoping to help recent victims; Lee Daugherty, owner of Alexandre’s, who was the first bar owner on the strip to declare his outrage that his patrons, employees and friends were being attacked and vowed to do something about it.

Pomerantz said he used social media to arrange interviews, but making this documentary was different from others he had worked on. He was filming — and editing — in real time, he said, rather than trying to relate a story that was over.

Even as he was filming, Pomerantz explained, he didn’t know how the story would end.

As he continued to follow events, Pomerantz decided to focus on a core group of activists trying to make a difference with politicians, the police and in the neighborhood.

“They really inspired me,” he said, explaining how a group of people that hadn’t known each other before came together to create a group focused on helping the survivors and on beginning to make a difference immediately.

“They really inspired me,” he said, explaining how a group of people that hadn’t known each other before came together to create a group focused on helping the survivors and on beginning to make a difference immediately.Some, like John Anderson, signed up to participate in Volunteers on Patrol, helping identify troublemakers in the neighborhood, even managing to break up several potential attacks before they happened.

And then the furious activity slowed to a crawl.

“I shot all this footage and around Christmas things settled down,” Pomerantz said. “We were waiting for an arrest and nothing happened.”

So the documentarian said he decided to put together what he had. With no arrest, there wasn’t a traditional Hollywood ending. But, he said, it still makes a good story because it’s real life and, in the end, people made a difference.

For Dominguez, the story is personally frustrating, because there’s been no arrest in his or any of the cases. But Pomerantz’s film, he noted, is less about the crimes and more about the community reaction.

“It happened to enough loud-mouthed people,” Dominguez said.

Dominguez explained that nine months ago, he didn’t know any of the people now involved in SOS–Survivors Offering Support, the organization he founded with Rasnake and Burnett, or those putting together the protests or fundraisers for SOS.

“Discrimination forced us together through extenuating circumstances,” Dominguez said, adding that he hopes it starts a conversation in other LGBT communities as well.

Dominguez will appear with Pomerantz at the USA Film Festival premiere of Light Up Oak Lawn, participating in a question-and-answer session after the screening. He expects people to ask where things stand now, and he hopes questions like that will start a conversation about the LGBT community working with the city, police and district attorney’s office to make the community safer.

Daugherty founded Take Back Oak Lawn and pulled Cedar Springs merchants and bar owners into the coalition of groups working to make the gayborhood safer. In the film, the bar owner talks about how business owners did — and didn’t — respond. He said businesses on the Cedar Springs Strip had always invested in safety inside their properties.

But, he urges them, “Don’t let it stop at the door.” And he complimented Zephyr, a new restaurant on Cedar Springs Road, for installing an advanced camera system.

“The Round-Up upgraded to an amazing camera system,” Daugherty added, “and Hunky’s is now adding cameras.”

Although news about the attacks is fading and no new attacks have been reported to police in recent months, the business response is continuing.

“We’re seeing a decrease in crime,” Daugherty said. “The stuff we’ve done is continuing to work and the community is not being complacent.”

The film premieres at the USA Film Festival at 6:30 p.m. on April 21 at the Angelika Film Center, 5321 E. Mockingbird Lane. Q&A with Pomerantz and Dominguez follows the screening.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 15, 2016.