As liver disease surpasses virus that causes AIDS as a killer, it should be a wake-up call for LGBT people to get tested, educated about risks

After the emergence of HIV/AIDS and the devastation it caused in the 1980s, the identification of yet another deadly virus about the same time went virtually unnoticed by the general public.

After the emergence of HIV/AIDS and the devastation it caused in the 1980s, the identification of yet another deadly virus about the same time went virtually unnoticed by the general public.

News and concern about Hepatitis C understandably took a back seat to HIV, and so the liver disease apparently grew exponentially because it was a slower killer and asymptomatic.

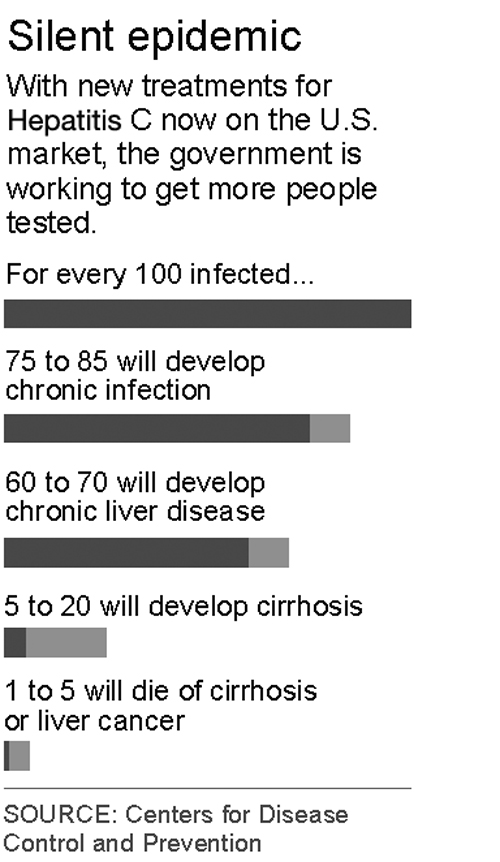

Spread mostly by blood-to-blood contact, HCV is now thought to infect as many as 170 million people worldwide, many or most of whom are unaware of their status because of the absence of any symptoms they are ill.

Often people do not become aware of their infection until significant damage is done to their liver, and cirrhosis or cancer develops and a transplant is necessary.

Now, more people die from HCV-related illnesses than those associated with HIV, according to a study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control that was unveiled this week.

CDC officials warn that Baby Boomers, anyone born between 1945 and 1965, should get a test to determine whether they are infected with HCV.

CDC officials warn that Baby Boomers, anyone born between 1945 and 1965, should get a test to determine whether they are infected with HCV.

Federal health officials estimate that two-thirds of the people infected with HVC are in this age group, and that half are unaware of it.

Medical researchers and practitioners theorized since the 1970s that another hepatitis virus existed in addition to Hepatitis B because some patients who no longer exhibited traces of HBV in their blood continued to show similar signs of liver malfunction.

Finally, in 1989 Hepatitis C was proven to exist, and widespread testing of blood for the virus since 1997 has revealed its frightening spread.

Many people in the LGBT community were unaware of the existence of HCV and only learned about it if someone they knew was diagnosed with it or, God forbid, learned they themselves had contracted it.

After dodging the HIV bullet and vowing not to place themselves at risk of contracting it, many people no doubt were shocked to learn there was yet another virus they could have contracted through blood transfusions, shared intravenous drug use and sexual activity.

What’s worse, there are concerns that the transmission of HCV might occur more easily than HIV through unsterilized medical and dental equipment, body piercings, shared personal items such as razors, toothbrushes and manicure tools — and no telling what else.

In contrast, HIV is thought to be less easily transmitted.

The possible presence of HCV was sometimes detected in the early 1990s among patients who got annual physicals because routine blood tests revealed irregularities in liver enzymes.

Further testing to identify the cause could reveal the presence of HCV when patients were in the care of doctors who stayed abreast of the medical developments.

It became clear HCV would become a chronic infection for most people who contracted it, and that it would eventually lead to severe health problems or death.

Only a few people would contract the virus and overcome it through the body’s natural processes, as is thought to be the case with some people who are exposed to HIV.

Two people of whom I have known and were HCV-positive illustrate just how widespread the virus could ultimately be.

One individual was a gay man who was a former heavy intravenous drug-user and HIV-negative, but nonetheless a member of a high-risk group.

The other was an older married female who didn’t even drink, let alone do drugs or engage in sex with multiple partners. She would surely be considered a member of a low-risk group, and I suspect she contracted the virus in a hospital setting long before its existence was known.

There are treatments available for HCV, but they unfortunately have different levels of effectiveness among patients, are expensive and can be intolerable to some people. Both of the people I knew were unable to tolerate the treatments. The heterosexual female has died, and I have lost contact with the gay man I knew who was HCV-positive. The last time I talked to him he had been declared disabled because of his HCV infection and the damage it had done to his liver.

In both cases, the months-long treatments that included injections and oral drugs caused flu-like symptoms and severe depression. They both abandoned the treatments.

Fortunately, other people managed to survive the treatments and the combination of drugs apparently eliminated HCV from their blood.

The very fortunate discovered the infections and received the treatments before irreversible damage was done to their livers as was indicated by biopsies.

At the time the two people I knew tried the available treatments, only a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin was available.

Those treatments initially were prohibitively expensive, but they are considered less costly now.

Today, there are new protease inhibitors available for treatment showing promise, but the cost is astronomical.

The new drugs, Victrelis at $1,100 per week, and Incivek at $4,100 per week, must be taken for months, and they also can cause hideous side effects.

It’s an agonizing situation, but most people are willing to spend whatever it costs if they can and endure whatever pain comes along in an effort to survive. That’s why it’s so important to get tested for HCV and to determine whether treatment is needed before it’s too late.

For others who are uninfected, don’t go there in the first place. Know how HCV is spread and avoid any possibility that it can imperil your life.

David Webb is a veteran journalist who has covered LGBT issues for the mainstream and alternative media for three decades. Contact him at davidwaynewebb@hotmail.com.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February 24, 2012.