Gay ex-players on how and when someone in NFL will finally come out

JOHN WRIGHT | Online Editor

wright@dallasvoice.com

With a combined 106 players on the rosters of the Green Bay Packers and Pittsburgh Steelers, it’s all but certain that a few participants in Super Bowl XLV will be gay or bisexual.

Needless to say, though, when the two teams take the field at Cowboys Stadium in Arlington on Sunday, Feb. 6, we won’t know who those players are.

In the 91-year history of the National Football League, not a single active player has come out.

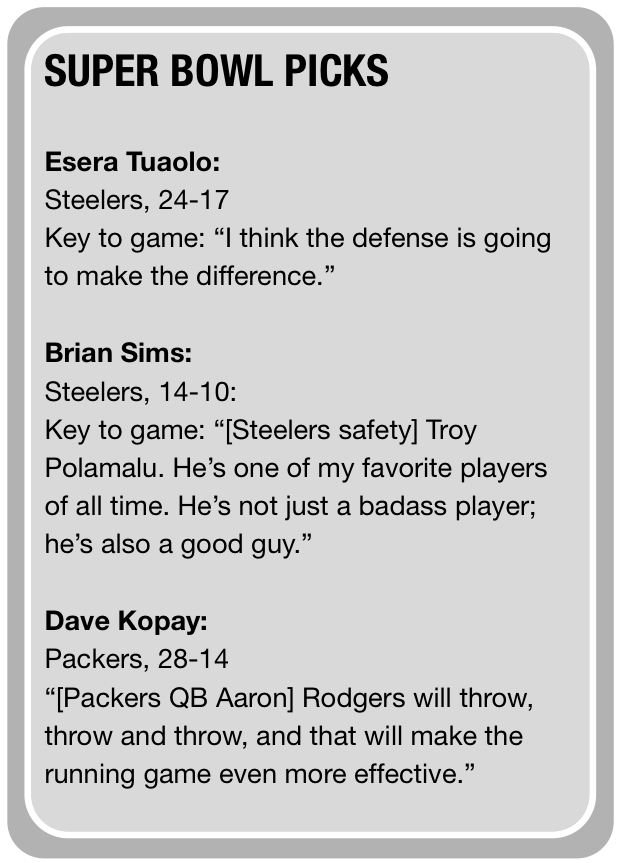

And only three former players have come out after retiring from the NFL — Dave Kopay in 1975, Roy Simmons in 1992, and Esera Tuaolo in 2002.

“What I find kind of disappointing is that sports seems to be the last bastion,” said Howard Bragman, the famous gay publicist who specializes in helping athletes and celebrities come out. “We even have seemingly won the military.

“I think the fans’ attitudes are changing,” said Bragman, whose clients have included Tuaolo and John Amaechi, the former professional basketball player who came out in 2007. “I think it’s all going to change, but we’re not there. We’ve scratched the surface of progress. We have an awful long way to go.”

Bragman said he believes one reason why no NFL player has come out is that it would put the person in physical danger on the field.

“I pity the guy who’s the first NFL player to come out,” Bragman said. “I think there are some vindictive people in the league.”

Although an out player’s teammates might rally around him, especially if he’s popular and has been around a while, he would run the risk of cheap shots from opposing teams, Bragman said.

“In the NFL you could shoot somebody and you’re probably not going to be hated as much as if you came out,” he said. “I think it’s really one of the last places that we have to fight homophobia and we have to fight a lot of myths and a lot of stereotypes, when these Neanderthals say things like, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t want to shower with one.’ It’s like, have we ever heard a story of a gay man attacking a straight man in the shower? I don’t think so. It’ just crazy.”

Still, Bragman and others say they see signs of progress.

Anti-gay comments from NFL players, once seemingly condoned, now draw discipline from NFL teams, and sometimes condemnation from others in the league.

A few straight NFL players, such as linebacker Scott Fujita of the Cleveland Browns (formerly of the New Orleans Saints), have spoken out publicly in support of LGBT equality.

But even so, Bragman said he believes the first NFL player to come out will do so involuntarily.

“I don’t think the first person who comes out in the NFL is going to come out pretty,” Bragman said. “I think the first person who comes out in the NFL is going to be outed, because we live in such a transparent world, and there’s going to be a picture that comes out or something like that that happens, as opposed to someone goes, ‘Hey, I’m gay.’”

Bragman noted there are no out players in pro baskeball, hockey or baseball, either, but he said he expects that to change soon.

“Within five years we’ll have two or three out men’s players in one of the major sports,” he predicted.

Others, meanwhile, believe the first openly gay NFL player will be someone who came out in high school or college.

Brian Sims, who came out while he was a team captain for the Division II football team at Bloomberg (Pa.) University in 2000, remains the only known active NCAA player to have done so.

“The first [NFL] player who comes out is going to be a Jackie Robinson,” Sims said, referring to the first black major league baseball player. “I think they’re going to be famous. I think they’re going to be a millionaire. But it will probably be somebody in college that was out and is just too good to ignore, which means probably one of the

skill positions.

“He’ll be too good not to draft, and a team like Miami, a team like New York … Somebody like that will pick him up proudly and say: ‘Yeah, you know what? We’ve got a built-in fan base just for this player alone.’” Sims said. “And it will be overwhelming how supportive people in the league will be.”

Sims, a defensive tackle who was universally accepted by his teammates when he came out, is now a Philadelphia-based attorney who specializes in LGBT civil rights.

Sims frequently speaks on the issue of homophobia in sports to athletes and students on college campuses.

He said he’s encouraged by the fact that there are out athletes in some sports on every campus he’s visited. And while none of them are football players, he says he knows gay football players at both the collegiate and pro levels.

“Some of them are living very closeted lives, very afraid of the repercussions,” Sims said. “Some of them are able to live relatively out lives in big cities …

“There are [NFL] players I know who are out, who have partners, and they’re able to be out with friends and with family. … They don’t sneak off once a month with their partner.”

But Sims, who believes a gay NFL player would represent a huge milestone for LGBT equality, said he doesn’t expect the players he knows to come out publicly anytime soon.

But Sims, who believes a gay NFL player would represent a huge milestone for LGBT equality, said he doesn’t expect the players he knows to come out publicly anytime soon.

“I wish they would,” he said. “I’m one of the people that if you’re a closeted gay football player in this county, I’m one of the people that you shoot a message to. You would be amazed if you saw the amount of, ‘Hey, do you mind if I share something with you?’ kind of e-mails that I get.”

Tuaolo, 42, who played with five different NFL teams in nine years, said he knows firsthand why gay players in the NFL don’t come out.

It’s “the fear of working your ass off all your life to get where you’re at, and then just to know you could lose it all,” said Tuaolo, a defensive lineman who played in the Super Bowl for the Atlanta Falcons in 1999.

“I was afraid to type in the word ‘gay’ in college in a computer, because I thought it would come back to me,” Tuaolo said. “It’s the fear that you live in, it’s the anxiety that you live in, it’s the hurt that you live in when you’re in the closet. I didn’t know of all these organizations that are so supportive in the gay community. You kind of live on this island.

“When I was in the closet, all I saw was the people who didn’t support us,” Tuaolo added. “All I heard was the people who didn’t support us.”

Tuaolo, who now lives in Minneapolis, said he’s been amazed by the support he’s received since coming out.

He also said he believes coming out in the NFL would be much easier now than just 10 short years ago.

“The reason being, everybody knows a gay person,” said Tuaolo, a frequent speaker at both colleges and Fortune 500 companies. “Ninety-nine percent of people raise their hands when I ask, ‘Do you know a gay person?’

“If a gay athlete comes out while he’s still playing now, I think a lot of his teammates will have to answer to their families, because all of them know a gay person,” he said.

Tuaolo, who hid his partner from teammates while in the NFL, is the father of adopted twins — a boy and a girl — who are now 10.

“It’s great to take my son to the [Minnesota Vikings] game and everybody knows,” he said. “It’s an amazing feeling to get that support from people.”

But in a sign that homophobia is still pervasive in sports, Tuaolo acknowledged that he’s dating a semi-pro baseball player who isn’t out to his team.

“We’re out to our friends and our family, but not out to his teammates,” he said. “I know how it is and stuff. When he’s comfortable and he’s ready to tell his teammates, perfect.”

Kopay, 68, now retired from a post-NFL career in sales, said he’s convinced there are gay players on every NFL team.

But Kopay, who played in the NFL from 1964-72, came out in 1975 and wrote a best-selling biography in 1977, isn’t overly disappointed that no active NFL player has come out in the 36 years since he did so.

“How many hundreds of years did it take the black folks to get the civil rights law passed?” Kopay said. “Look at the progress we’ve made.”

A one-time Army Reservist, Kopay said he “cried like a baby” when “don’t ask don’t tell” was repealed late last year.

Also last year, Kopay attended the Super Bowl as a guest of Indianopolis Colts assistant coach Howard Mudd, his former teammate.

Kopay said he got a warm welcome from players and coaches during the trip, but it was also bittersweet knowing that anti-gay bias likely prevented him from following the same path as Mudd.

“Certainly I would have loved to have been a coach,” Kopay said. “It was painful for me, because it reminded me of my lack of doing what I always really wanted to do, but never got a chance to do.”

Kopay now lives in Seattle near his alma mater, the University of Washington, where he’s been named one of the 100 most influential graduates in the school’s first 100 years — largely because of his impact on gay rights (although he was also an All-American running back).

Kopay doesn’t travel or speak publicly as often as he used to, and he recalled one occasion last fall when he was invited to Arizona State University. Kopay said the ongoing gay youth suicide crisis weighed so heavily on his mind that he had to cancel the trip.

“It was so painful to think about, how there’s still been so little progress,” Kopay said. “I just got feeling so blue and angry that I couldn’t get my words out when I started reading and practicing delivering my speech. It brought me back to a place — it brought the anger in me.”

For Kopay, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that if LGBT youth had a professional athlete to look up to, they’d be less likely to give up hope. But he also said he’s comforted by the thousands of e-mails he’s received from people he’s inspired in other professions.

“It’s almost like I gave them permission to be who they were,” Kopay said. “It’s daunting to think about that, but it happened, and I’m really pleased that it happened. It’s incredible. That’s what gives me a sense of purpose in life, and a sense of happiness.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition Feb. 4, 2011.