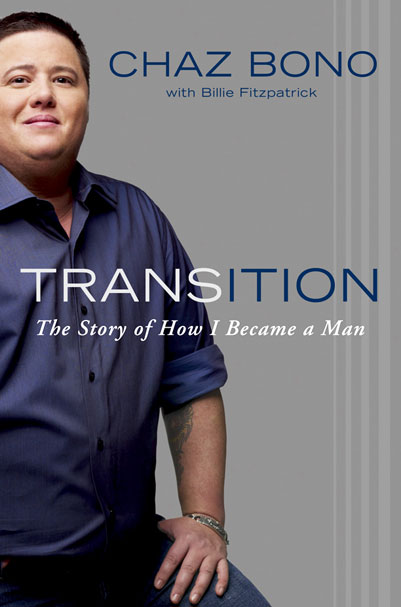

Transition by Chaz Bono (with Billie Fitzpatrick), (2011, Dutton), $26; 245 pp.

The face in the mirror is instantly recognizable: The chin, the eyes that droop when fatigued, the mouth that’s etched parentheses around itself. The hair, they eyes, the nose. But what the little girl America knew as Chastity Bono saw on the outside was not what she felt inside.

In Transition, the biological daughter of pop icons Sonny and Cher explains what it’s like to feel like you’re in the wrong body, and how a tiny Hollywood darling went from daughter to son.

On the wall of his home, Chaz Bono has a picture of himself and his parents, taken when he was a toddler. They all look happy, though Chaz says he doesn’t remember the day it was taken —or much else of his childhood, for that matter. What he does remember is that he always felt like a boy.

As a kid, he dressed in boy duds as often as possible and answered to a male nickname. He played with boys at school, including his best friend. Nobody thought much about it, he says — that’s just how it was.

Puberty was rough; eventually, Bono came out as lesbian, but something still wasn’t quite right. He didn’t identify with women, gay or otherwise, and distant feelings of masculinity colored his relationships with them and with his family. Still, he lived his life as a woman: falling in love, starting a band, buying a house and trying to stay out of the public eye.

Bono’s father seemed supportive of his lesbianism; his mother had trouble with it. Happiness eluded Bono so he turned to drugs to cope with the frustration. By then, though, he thought he knew what he needed to do.

On March 20, 2009, he “drove myself to the doctor’s office… I felt only confident that what I was doing was right. … After all the years of fear, ambivalence, doubts and emotional torture, the day had finally come. I was on testosterone, and I have never looked back — not once.”

Chaz says he was never very good at transitions, though he did a pretty good job at this one (with a few bumps along the way).

Transition is filled with angst, anger, sadness and pain, but topped off with wonderment and joy. It’s also repetitious, contains a few delicately squirmy moments, and its occasional bogginess is a challenge for wandering minds.

For wondering minds, however, Chaz is quick to defend and explain away his family’s reluctance to accept his gender reassignment, but he’s also willing to admit to being hurt by it. Still, contentment and awe shine forth at the end of this book, and readers will breathe a sigh of relief for it.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition May 27, 2011.