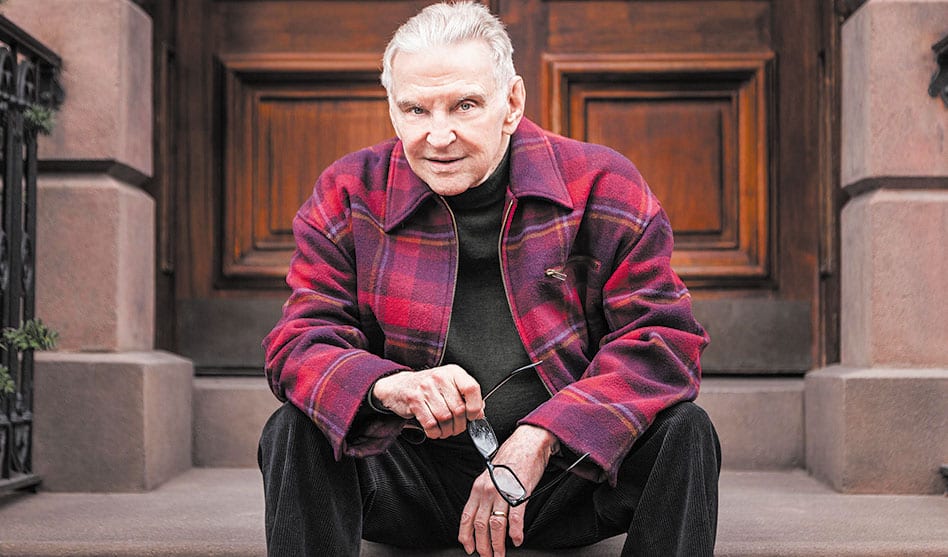

Memoirist Martin Duberman, above, finally addresses a missing decade in his life, one tinged by depression and addiction, in his book ‘The Rest Of It.’ (Photo courtesy Alan Barnett)

Memoirs of lost years, faith and military service

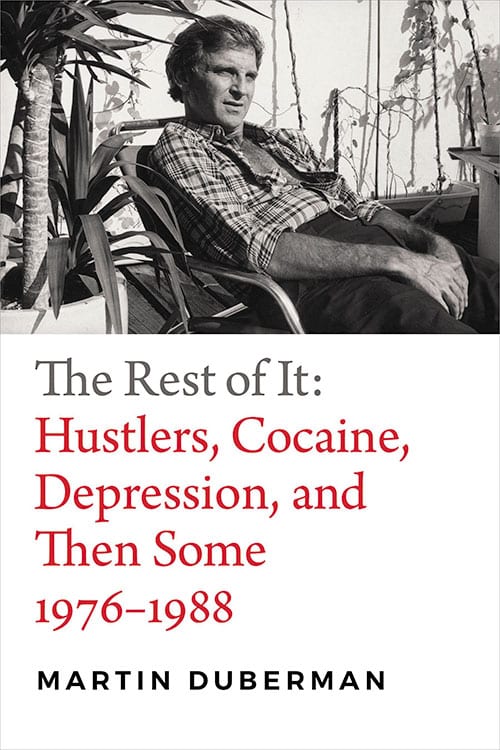

The Rest of It: Hustlers, Cocaine, Depression, and Then Some 1976-1988 by Martin Duberman (Duke University Press 2018) $27.95; 242 pp.

The Rest of It: Hustlers, Cocaine, Depression, and Then Some 1976-1988 by Martin Duberman (Duke University Press 2018) $27.95; 242 pp.

Having penned other memoirs, Martin Duberman says that people often ask him why he’s omitted roughly a decade of his life story. Once noted, he realized that “the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties… were the most painful years of my life.”

They began with his mother’s illness in late 1976, and her surgery for cancer that was initially said to be non-cancerous, but that was finally diagnosed as malignant melanoma. Duberman had had a complicated relationship with his mother, but they’d made their peace; still, hers was a horrible death, and it plunged him into his work and a bout with depression.

For years, Duberman had been involved in the LGBT community as an activist, and “in the wake of my mother’s death I hadn’t jumped ship, hadn’t abandoned academia or run off to join the circus.” Still, he looked for ways to cope: he had his circadian chart read, and he used a fair amount of cocaine and pot. He immersed himself in projects, both of the literary kind and for the gay community, and he picked up his political engagements. Duberman worried that the stress was bad for him — and he may’ve been right, because he had a few health scares, including a heart attack, and another bout with depression and “desperation.”

Still, he continued to write. It was a time “of a flowering of gay culture” when many gay literary giants were publishing, and that included Duberman himself. It was a time when bathhouses dotted New York City, AIDS was emerging as a crisis … and Duberman was celibate and addicted. It was a time when he had nearly hit bottom before he found help and love.

You may be thinking that The Rest of It sounds as if it’s on the self-contemplative side, and you’re right (many memoirs are). What keeps you reading isn’t the biography that Duberman offers but what’s behind it.

Duberman’s life was keenly interesting in the dozen years between 1976 and 1988, but so were then-current events, which he carefully recounts. This book shows an emergence of gay culture on a larger scale, growing activism, and the dawn of AIDS; his voice is occasionally snarky as he takes on the medical establishment of the times, gay nightclubs and bath houses, and Reagan politics. In these ways, his deeply-personal memories, mixed with what happened when, are vastly more appealing than if this book were mere memoir.

Though it may not attract casual-readers under “a certain age,” this book is perfect for older readers who remember these times. Also, for historians’ bookshelves, The Rest of It shouldn’t be missing.

Given Up for You: A Memoir of Love, Belonging and Belief by Erin O. White (University of Wisconsin Press 2018) $26.95; 192 pp.

Given Up for You: A Memoir of Love, Belonging and Belief by Erin O. White (University of Wisconsin Press 2018) $26.95; 192 pp.

Missing the last train back to her home was no problem. Actually, Erin White was glad for it. She was anticipating what could happen next. She’d never slept with a woman, had never even considered it but, on that night she met Chris at a dinner party, it was all she could think of. It was odd but thrilling, so by the time Chris told their hostess that White could stay at her apartment that night, White was already in love.

What would she tell her therapist? She knew he would disapprove — and he did, but they rarely discussed White’s relationship. Mostly, they talked about God.

For some time, White had been exploring that which her soul seemed to crave and, at her therapist’s urging, she read the Gospels and was stunned by the words. She cautiously attended Catholic services and began learning more about God and religion; eventually, she broke up with Chris, who’d been raised in the Church and avoided it as an adult, but White couldn’t stay away.

It was difficult to explain, she says. She was a lesbian, but she wasn’t; in fact, there were times when “lesbian” just felt wrong. As for God, she needed to know Him better. White wanted “to love a woman yet avail myself of the opportunities… of straight culture; to break the rules of the church but still feel myself beloved by it.”

But since nobody can have everything both ways, she made her choice.

Two kids, fights, triumphs and a strong marriage later, she sees things in a different light. Church is comfort now. It’s home. But to get to that point, it took the courage to say “I loved that crazy Church, I loved those wild ideas about God, and I gave them up because I also wanted you.”

Although it’s already pretty short, Given Up for You feels crowded. White offers a three-pronged memoir of love, faith and motherhood, and that’s a lot to pack into such a small space. Still, while readers may struggle with overabundance of story, there’s a lot to come away with. White’s search for faith is universal and easily understood; although she might have explored homophobia a bit more, the subject of gay Christians and her experiences are presented in a way that’s calm and thoughtful.

Enter into this book knowing that it’s sometimes slow. Beware that it’s a bit long. Read it with a perfectly happy willingness to (gasp!) skip paragraphs and Given Up for You may belong on your bookshelf.

Tell: Love, Defiance, and the Military Trial at the Tipping Point for Gay Rights by Major Margaret Witt with Tim Connor, foreword by Colonel Margarethe Cammermeyer (ForeEdge 2017) $27.95; 258 pp.

Tell: Love, Defiance, and the Military Trial at the Tipping Point for Gay Rights by Major Margaret Witt with Tim Connor, foreword by Colonel Margarethe Cammermeyer (ForeEdge 2017) $27.95; 258 pp.

For those who love her, Margie Witt has always been known as an active, take-charge, caring person. A tomboy growing up, she befriended the friendless, got along with everyone, and was a super-responsible leader. It was, therefore, a natural fit when, in 1987, Witt decided to join the Air Force, even though she was gay.

But, of course, nobody was supposed to know that. As an elite member of the military, Witt fully understood that just being gay meant a military discharge. By order, nobody could ask her about that, though; she, in turn, could not discuss her sexuality.

Still, because secrets are never totally secret, Witt was ever-cautious. Fearing rejection, she hadn’t come out to her parents or her siblings yet; on the other hand, close pals knew that Witt was a lesbian, as did a fellow reservist who’d defied DADT in order to put his suspicions to rest.

Even Witt’s girlfriend was mum, but there was trouble on that front: Tiffany desperately wanted a baby and was pressing, but Witt was uninterested in parenthood.

With a pregnancy deadline-or-else looming, Witt took solace not only in her job as a pediatric physical therapist in Spokane, Washington, but also with her friends in the Air Force Reserve and her work as a flight nurse. She kept busy, was sent overseas to the Middle East, and received commendations for saving a life there. Her knowledge was admired and, as her relationship crumbled, her natural sense of humor helped her stay level, but she needed a confidante. Witt turned to a married-but-“struggling” female colleague who soon became more than just a friend with a sympathetic ear.

And in the ensuing “’very, very ugly’” divorce, in which a soon-to-be-ex-husband seized upon two women spending the night together, DADT was no longer possible…

That, of course, is not the end of what you’ll learn inside Tell.

There’s much more to the story, sometimes too much. In an oddly appealing third-person voice, Witt starts her tale with a deployment and moves quickly to a charmingly nostalgic biography that ultimately loses some of its charm in an overload of details. There are a lot of peripheral people in this tale, the presence of which sometimes feels more shout-out and less necessity.

Stick around: the details have a shift of focus about mid-way here, once you get past the set-up and into the books’ raison d’être. Things move faster in the re-telling of the legal aftermath of Witt’s exposure, the fight for gay rights in the military, and Witt’s own (mostly)-happily-ever-after. That’s what makes this slice-of-life history tale one that’s highly readable and deeply personal.

That’s what makes Tell a score.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer