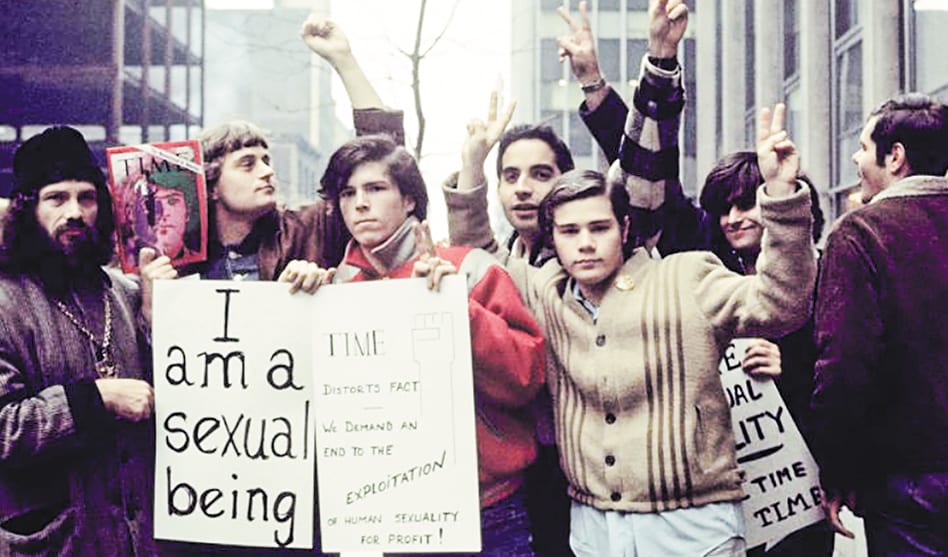

Mark Segal, now publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, was 18 years old and newly-moved to New York City that night that the police raided the Stonewall Inn and the patrons decided to fight back. He spent the next year on the front lines of the fight for equality with the Gay Liberation Front. (Photos courtesy of Mark Segal)

The rebellion didn’t end after a few June nights, thanks to the Gay Liberation Front

Mark Segal | Special Contributor

mark@epgn.com

That night, standing in Stonewall, I could not have imagined what the next few hours would do to change the gay and lesbian community around the world. I doubt anyone else could have known. How could we have known, on June 28, 1969, that we’d be participating in history?

It started when the lights flickered on and off, alerting the patrons that something was imminent, though I had no idea what. It was just my second month in New York, my second month walking Christopher Street, my second month being an out and proud gay.

Looking over at my friend, I asked what was happening. He answered nonchalantly, “Oh it’s just a raid.” As an 18 year-old, new to everything, his words were frightening to me.

The police barged in, pushing around anyone who was in drag or stereotypical-looking. They hurled insults and hurled people around.

Anyone who looked like they were successful, anyone who had a few bucks, was forced to take out their wallets and, in the bright light, give their money to the cops, who slid the bills in their pockets. Welcome to Extortion 101.

They robbed us in plain sight, and we had no possible recompense. That is how they felt about us. That’s how they felt they could treat us — any way they wished.

As this was happening, they began to clear the bar by carding people. To this day I don’t know why they were carding, since it was an illegal bar and drinking age didn’t matter. But that was the procedure.

At 18 and fresh from Philadelphia, I looked like the boy next door. They had little use for me, and I was one of the first to be carded and let out. And I was glad about that.

At 18 and fresh from Philadelphia, I looked like the boy next door. They had little use for me, and I was one of the first to be carded and let out. And I was glad about that.

But as I came out, I saw an obvious difference in what certain clientele were doing. Those with family ties, those with a good job, those on the fast track to a professional career — they all ran for the subway as soon as they could get out that door. But people like me, a street kid living at Sloane House YMCA on 34th Street, and others who today you’d call trans — we just stuck around.

We had nowhere safe to go. Our safety was with each other, right there, watching what was transpiring.

Eventually there were more of us outside, and inside the bar remained only the police and employees. Those of us who stayed formed a semi-circle around the double doors into the street. My memory tells me that there were between 50 and a hundred of us.

The doors opened, and the police shouted out a few insults and told us to disperse. We didn’t.

They opened the door a second time and again spewed insults, demanding we disperse. We didn’t, and this time, we yelled insults back at them.

They closed the door, and at that point, people picked up whatever there was around them — stones, discarded soda cans and bottles.

For the first time in history our community wasn’t just fighting back. We had imprisoned our oppressors, the police. They were now our prisoners.

This continued for some time, and it was awhile before police’s re-enforcements came to their rescue. It is my belief that the reason for the slow re-enforcements was the officers inside that gay bar were too embarrassed to call their station house and have to tell their fellow officers, “We’re trapped and surrounded by angry fags and dykes. Please save us.”

The fact that we had them trapped created a certain joy on the street. People began to run to other bars in the area; passersby turned their heads as they came around the corner.

While this riot was happening, Marty Robinson, who had created something called The Action Group, came up to me with chalk, telling me, “Write on the walls and street: ‘Tomorrow Night, Stonewall.’”

I have no idea where he got the chalk, but I’m thankful he got it. That chalk was a catalyst for much more than one night of rebellion.

From the river to Greenwich, all along Christopher Street, I wrote: “Tomorrow Night, Stonewall.”

People ran and screamed and laughed. It was a joyous evening. We were fighting off 2,000 years of oppression, though we didn’t realize it in that moment.

Amid the joy and the excitement, I had a light bulb moment. Standing across the street from Stonewall, watching everything happening around me, I thought to myself, “Black people are fighting for their lives, Women are fighting for their lives. Latinos are fighting for their lives. What about us? What about me?”

It was at that point that I finally knew what I’d do for the rest of my life: I would be something that didn’t exist yet, something that didn’t have a title, something that had no salary. I would be a gay activist.

I didn’t know — and I didn’t care — how difficult it would be. All I knew in that moment was that I found what I was meant to do.

I was at a riot that started a revolution, and I would be a part of that revolution.

In the commotion, I saw a window broken. I didn’t see any Molotov cocktails. I saw a feather boa being put on the statue of Gen. Sheridan in Sheridan Square. I wasn’t there when anyone was arrested, but I was there each and every night that followed, along with all of us who would later call ourselves Gay Liberation Front.

It was the members of GLF who wrote on the street that night, members of GLF who stood proudly at the front doors of Stonewall the second night to hear Marty Robinson and Martha Shelley speak, members who understood the changes we were demanding, not asking for.

The third and fourth nights were filled with organizing and a circus atmosphere that continued throughout the entire week. We were joyous, since from the ashes of Stonewall came the Gay Liberation Front, a group that would turn our community and the world upside down.

Also, from the third night on, leafleting began on Christopher Street. For the first time we were united, and for the first time we were a diversified community.

Let’s make this clear: Before GLF, you didn’t see anyone but white men in suits and ties and white women in dresses representing the LGBT community.

Those earlier organizations wouldn’t have anyone else as spokespeople.

That is why I was in The Action Group. Mattachine didn’t want me, a youth of 18, in their office since they felt they could be raided for corrupting the morals of minors.

And drag queens, people of color? They were ignored by those groups.

But we in GLF welcomed all. From lesbian separatists, to radical fairy collectives, youths, street kids and yes drag queens — they were all GLF. You may have heard about a couple of our members: Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. They were welcomed, too.

GLF is the most important LGBT organization to have ever existed, because we made more change in one year for this community than any other organization has since. And we also were certainly the most dysfunctional — and we are all proud of that!

That first year, from Stonewall to the first Gay Pride in 1970, was pure magic, and it made our community what it is today. It changed our lives in so many ways that no organization had before.

We would no longer be invisible. We were out, loud and proud of who we were, and we would no longer accept society’s labels. We would tell them who we were.

We were not “homosexuals.” We were gay men, gay women, lesbian, dykes, drag queens.

Not only would we be open about who we were, we’d also be in your face to fight for our rights instead of merely pleading for them. This was all revolutionary, since 99.9 percent of our community was in the closet, and in 1969, before GLF, there were only four types of places to go — illegal gay bars, cruising areas, private parties and secret meetings of organizations, which were hidden so the police would not raid them.

But GLF advertised our meetings. We advertised that we were going to have a dance — women dancing with women, men dancing with men, and not in an illegal bar but in public. We dared the police to raid us, and they were afraid to.

That was rebellious!

We also publicly took back our street Christopher Street by leafleting every night and facing off against the police. We did legal alerts, medical alerts, notices to gather for our next demonstration, handouts for Gay Youth meetings, a hotline, the nation’s first trans organization, and the nation’s first LGBT Community Center. And if all that were not enough, we were the organizers and marshals for that very first Gay Pride march in 1970, which was called

Christopher Street Liberation Day March, originally dreamed up by Craig Rodwell and Ellen Broidy.

Stonewall was not one night, it was a year, and GLF was its spirit. That spirit of rebellion transformed our world.

Before Stonewall, less than a hundred out people represented us, all white men and white women, no diversity allowed. One year later at Gay Pride, people of color, trans people and youth gathered under a grassroots movement that welcomed all segments of our community. We were not 100 picketing once a year; we were now thousands.

I wasn’t just at Stonewall. More importantly, I was with Gay Liberation Front. Stonewall and GLF are synonymous, One night led to one magical year. A year that changed the world.

Mark Segal is publisher of The Philadelphia Gay News, and last year his personal papers and artifacts, including some from this article, were inducted into The Smithsonian Institute American History Museum in Washington, D.C. His memoir — And Then I Danced, Traveling The Road To LGBT Equality — was named book of the year by the National Lesbian Gay Journalist Association.