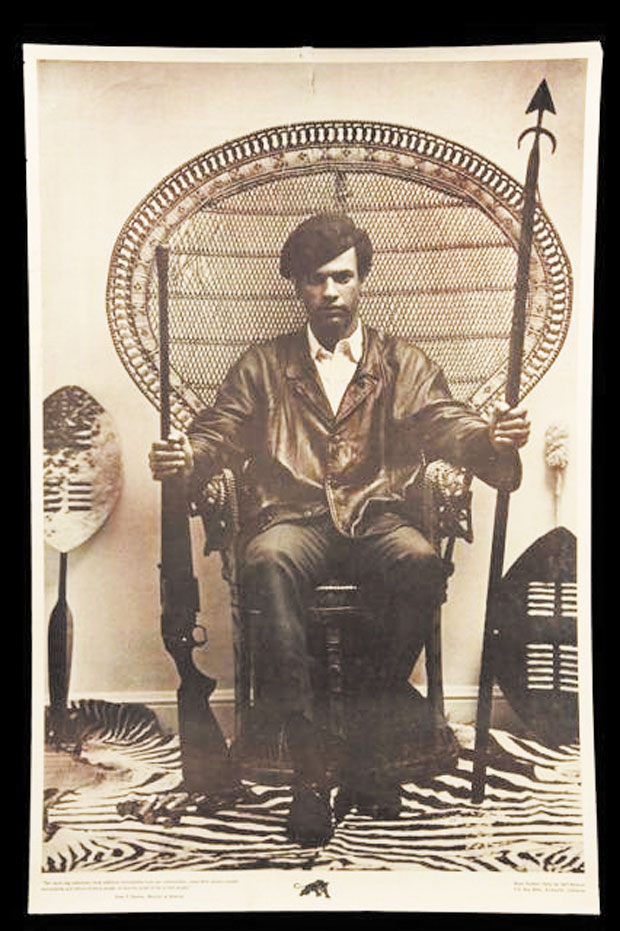

As we stand at a crossroads in our country, Black Panther Party cofounder’s call for unity still rings true

Huey P. Newton

‘During the past few years, strong movements have developed among women and among homosexuals seeking their liberation. There has been some uncertainty about how to relate to these movements.

‘During the past few years, strong movements have developed among women and among homosexuals seeking their liberation. There has been some uncertainty about how to relate to these movements.“Whatever your personal opinions and your insecurities about homosexuality and the various liberation movements among homosexuals and women (and I speak of the homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should try to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion.

“I say, ‘whatever your insecurities are’ because as we very well know, sometimes our first instinct is to want to hit a homosexual in the mouth, and want a woman to be quiet. We want to hit a homosexual in the mouth because we are afraid that we might be homosexual; and we want to hit the women or shut her up because we are afraid that she might castrate us, or take the nuts that we might not have to start with.

“We must gain security in ourselves and therefore have respect and feelings for all oppressed people. We must not use the racist attitude that the white racists use against our people because they are black and poor. Many times the poorest white person is the most racist because he is afraid that he might lose something, or discover something that he does not have.”

Over one year after the Stonewall rebellion in the summer of 1969 that set the movement for gay rights to move forward, Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, delivered these prophetic words in a speech that would come to be known as “his gay speech.”

Given the seismic shift in our country’s social and political rhetoric towards communities and groups who are still marginalized in the 21st century, despite the tremendous gains we have made to change that landscape, we still have much work to do. This holds true for blacks, for women and for the LGBTQ communities.

Arguably, the more visible and contentious display of vitriol has been FELT by the black and LGBTQ communities, although the latter has made significant progress in the fight for equality in the “land of the free, and the home of the brave.” Women have also seen tremendous gains in their fight for access and equality at all levels of society. But there are still challenges and glass ceilings that remain.

In the black community, vestiges from American slavery, reconstruction and the period of legalized, racial discrimination known as “Jim Crow” still persist, bringing with it the same old stereotypes about blacks that have resulted in a number of societal ills that white America continues to ignore, despite our shared past.

Black men — and some black women — have been the contemporary targets of that hatred in the form of killings by those sworn to protect and serve every citizen of this nation.

To be fair — and on a topic that is the subject of criticism by some in and out of the black community — it is my belief a number of those unfortunate deaths were justifiable based on the circumstances, and the police were simply doing their job.

BUT a higher percentage of those deaths involved excessive force that wasn’t justifiable.

Last week after the murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile (Yes, I’m calling them “murders” because that’s what they WERE!), that truth came home to roost in the latter category of unjustified force. And that chicken came and set down square in my family, in an indelible and personal way, through painful dialogues

Watching the second video of the killing of Alton Sterling that was in constant loop on every news station and in the media, I found myself growing angrier and angrier, because it was my opinion that the officer acted improperly and yet another black man was dead. To be completely honest, I wasn’t just angry; I was MAD AS HELL.

Before I had the opportunity to process this atrocity, Philando Castile was shot during a traffic stop, with his fiancée calmly sharing through live feed what was occurring before and after he was shot. She did so with a steely calm and resolve that I still don’t understand how she managed.

Castile’s death hit me harder. Why? Because he could have easily been me.

Like Castile, I work for my living and keep my nose clean. I am loved by the people I serve, in particularly their children. I care for my family and extended family members, as it is evident by the strong bond he had with his soon to be step-daughter that Castile did also.

And like Castile, I have a legal license to carry a handgun.

Equally as hard for me was the death of the five courageous Dallas polices officers who lost their lives during what was supposed to be a peaceful protest coordinated between the black community and the Dallas PD. I sat stunned as I watched the television, repeating over and over again, “This is not supposed to be happening in Dallas, Texas. Dallas, Texas? This does not happen here.”

I have lived by the model of responsible adulthood and citizenship all my life, virtues passed down to me from my parents, who were both in our home while I was growing up. I work extremely hard to live right, treat people well and leave something tangible for the next generation of my family and others outside of it to build upon.

What Castile’s death spoke to me was this truth: Regardless of my BEST efforts to do the right thing by myself and others, if stopped by the police for a basic traffic infraction that whites and other racial groups also get stopped for, in the end I might become the next statistic — or in my own words, just another dead-ass nigger.

Is that painful to hear? That word? The word that all of us better NOT utter? Well, it’s harder for me to mentally process because that’s how I’m viewed by a segment of white America, including some police — as a targeted group.

However, what was more painful was my husband and I receiving a call from our family in Illinois. Our 17-year old grandson, our ONLY grandson out of six grandchildren, was apparently upset by everything that was going on. I couldn’t speak to him; I was too angry. Gregory spoke to him, and our grandsom asked him this pointed question before breaking down: “Pappadeaux, why are they trying to kill us? Why do they want to kill us?”

That question from a young man on the cusp of his adult life haunts me to this day, because if I did have the ability to answer his question, I wouldn’t know what to say.

Perhaps I might say, “Grandson, I don’t know why they do that. All you can do is do EVERYTHING we taught you to do when engaging police officers. Be respectful. Answer all of their questions honestly and calmly. Don’t make any unnecessary movement that may be considered a threat. But above all, realize that if you do all of these things, Pappadeaux and PauPau can’t protect you if that officer sees something different. We can’t protect you and you may end up dead.”

I don’t know about you white community, but that is a really fucking hard pill to swallow. I am pretty sure you don’t have similar conversations with your own children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews and other loved ones — certainly not at that type of brutally honest level, given this climate.

So how do we address this epidemic of “living while black until you are killed,” that we are all witness to during this time in history — which by the way, is the same shit as usual, because this is NOT new. Blacks have been subject to racial profiling and killings for a very LONG time in this country’s history.

The only difference now is that we have smartphones to record all of this shit. And even then, you have people who walk by virtue of the badge, reminiscent of those walking because of the prominent display of their hoods and sheets, all perceived to be upright and moral citizens.

Perhaps the late Huey P. Newton was on to something powerful that we all missed: the collaborative merging of the three primary struggles for equality facing this country. Moreso than not, our movements need each other. Blacks. Women. LGBTQ.

Deliberate actions and progress for one group is progress for us all. But we have to be willing to go down this path together, for equality’s sake.

I was a participant in the recent prayer vigil for the Orlando tragedy sponsored by Resource Center here in Dallas, and I was overwhelmed emotionally at the sea of brother/sisterhood that event represented. LGBTQ, black, white, Latino, Asian, male, female, transgender, allies, politicos AND the police, all in solidarity for a TANGIBLY better America. I have never in my 20-plus years of advocacy in this country felt the kinship as I felt that day.

We deserve more than what we’ve been giving ourselves; my grandson and his contemporaries deserve more. We OWE them this.

And that will be our legacy to them, that they will no longer live in a society where a person is judged by their race, skin tone, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status or any other ism that divides us as a nation.

Buster Spiller is a happily married, longtime activist, and award-winning playwright from Dallas.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 15, 2016.