Jonathon McClellan

Author Jonathon McClellan’s 2 books are based on his own experiences with homelessness and schizophrenia

TAMMYE NASH | Managing Editor

nash@dallasvoice.com

Writing was my secret key to unlock the door back into reality,” said local author Jonathon McClellan, explaining the beginning of his career as a writer. Now, not only has he found and unlocked that doorway, he has stepped on through to write two books, both of which were recently published.

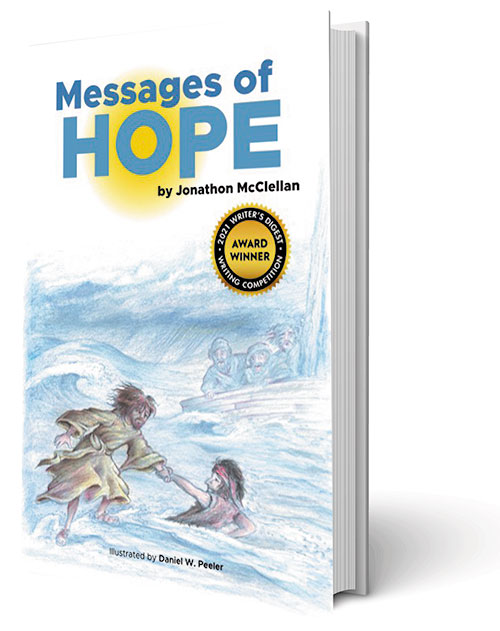

The first of the two is called Messages of Hope, and it is a devotional book of prose and poetry, “written in my own style,” for adults, McClellan said. “This is a collection of honest conversations between me — at my lowest, weakest and most vulnerable — and God. It’s something I wrote not knowing that it would ever become an actual book.”

He said he wrote Messages of Hope when he was fighting with schizophrenia, loneliness and bereavement.

“I had made many attempts at taking my own life, and I was looking for a way to silence the background noise. Writing was that way for me, that place I could go to that was safe,” McClellan said. “Then I started sharing [my writings], and as I did, I realized that I needed to share them. I realized that the messages I was getting weren’t just for me. So I decided to take a leap of faith and just put it out there.”

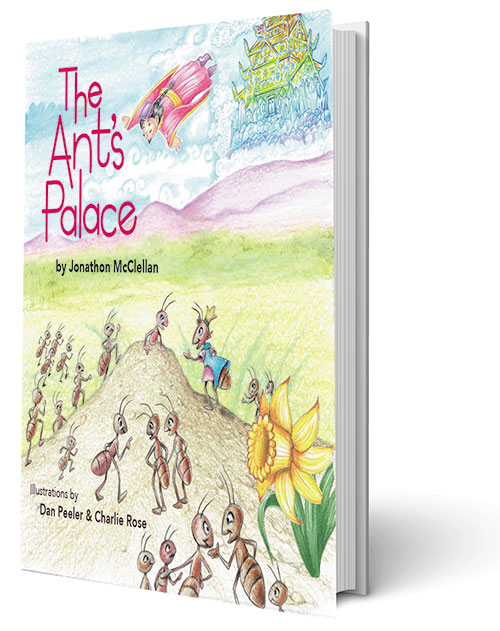

McClellan said his second book — a children’s book called The Ant’s Palace — was also born of his desire to share what he has learned through his own tribulations. The book tells the story of King Hoseki (which is Japanese for “Jewel”), an immortal king who lives all alone in a glorious palace made of diamonds, which catch the sunlight and reflect to bathe his palace is rainbows.

But despite his opulent home and his immortality, King Hoseki never smiles.

One day, he decides to travel the world, to prove to himself that his kingdom is the greatest and his diamond palace is the most glorious. When he travels south, he finds a group of orphaned children, huddling together with no home, and yet they are smiling. Shocked and befuddled, he goes into a garden to think about these children. While there, he sees an ant, Queen Doro (Japanese for “earth” or “dirt”), crawling past his foot, followed by her devoted army of ant subjects. Although he has little respect for this lowly ant, he asks why it is her subjects love her so. She answers that while she may only live in a palace made of dirt, she shares it with and is surrounded by those she loves.

That is when King Hoseki realizes that no one ever sees the beautiful rainbows in his diamond palace, and that it is better to live in the dirt surrounded by loved ones than to be alone in a diamond palace. So he goes back to the orphans and invites them all to come and live in his palace with him, pledging to be their kind and loving father from then on.

That is when King Hoseki realizes that no one ever sees the beautiful rainbows in his diamond palace, and that it is better to live in the dirt surrounded by loved ones than to be alone in a diamond palace. So he goes back to the orphans and invites them all to come and live in his palace with him, pledging to be their kind and loving father from then on.

This story, too, grew out of his own experiences, McClellan said. “I was homeless for a while when I was a kid. But I remember my seventh birthday party, which we had at the Faith Mission in Elkhart, Ind., where we were staying. We were homeless, living in a shelter, but at my birthday party, we were all so happy, and everyone was smiling.

“It was because we had community,” he continued. “We had each other. And when you have that, you have true wealth. I’ve learned that the bonds we make with each other are our true riches.

I’ve learned that emotional poverty is often far worse than financial poverty, and I wanted to write a story that disillusioned our misconceptions about what true wealth and true happiness really are.”

McClellan said he had a difficult childhood, his parents having split up before he turned 3. By the time he was 6, he and his mother and younger sister were homeless, and his mother was pregnant with her third child.

“After I turned 7, I found a place to stay, but things started falling apart there, too. I became a ward of the state, and I was in and out of foster care until I was 17. I even stayed with my dad a couple of times, but that didn’t work out either,” he said.

When he turned 17, McClellan said, “I took control of my own narrative. I stopped living in someone else’s story that was never meant to be my story.”

He moved first to Hollywood where he graduated high school and began to work on creating a career in music. Then he decided to move to New York to pursue a career on the stage. “I’m always looking for where I should be,” he said. “I live by my heart.”

He moved first to Hollywood where he graduated high school and began to work on creating a career in music. Then he decided to move to New York to pursue a career on the stage. “I’m always looking for where I should be,” he said. “I live by my heart.”

In New York, he said, “things started to click for me.” He went to work for Children International “to pay the bills,” and that opened the door to “lots of grassroots work” with other organizations like Greenpeace, Planned Parenthood, Save the Children and Park 51, the Islamic organization trying to build a community center near the 9-11 Ground Zero location.

“They were just trying to give back to their community,” McClellan said of the controversial project. “I was always confused at how prayer could be so offensive to anyone.”

But by the time he turned 23, McClellan had begun to develop schizophrenia. “I went into a tailspin,” he said. “I ended up homeless again, and I hitchhiked across the country.

“It was a hard time, but I saw a lot of beauty then, too. I meditated a lot; I wrote in my journal. I was trying to make sense of a senseless world.”

He said that is when he discovered writing as his key back to reality. He found the right therapist and the right psychiatrist, and they got him on the medication he needed to control and manage his condition.

“That changed my life for the better,” McClellan said “I still had a lot of trauma to recover from, a lot of psychological abuse to overcome. And sometimes I tried giving up. I was so convinced there was no hope. Believe me, I understand hopelessness intimately, in all its aspects.

“I tried to take my own life. But I couldn’t do it. Something always stopped me.”

McClellan said he made his way to Dallas because his mother and other family members live in this area. “I have always tried to maintain a relationship with my parents,” he said. “They did the best they could. And while I could use my platform now to talk about all my grudges, I don’t want to do that. The world does not need another voice of discontent.”

McClellan also found Cathedral of Hope when he came to Dallas, a community that, he said, is full of LGBTQ people who love God and also love themselves. “I was so used to living in a kind of religious Stockholm syndrome, [with LGBTQ people] who serve a God they also believe is always looking to shame them and who send them to hell.”

But at Cathedral of Hope, he found a new kind of LGBTQ religious community: “Cathedral of Hope is so accepting and so affirming,” he said. “This is a church that shows you that God loves you as you are.”

These days, McClellan said, he works full time as a writer. He writes devotionals for Believe Out Loud, a Cathedral of Hope program, and he writes other pieces for the church, as well. He also enters a lot writing contests, and last year, his story, “My First Bicycle,” about his 7th birthday at the homeless shelter, won Writers Digest’s 90th annual competition. “I was just shocked by it all,” he declared.

McClellan and his partner Paul just celebrated their two-year anniversary and are looking for a new place to live, something with more space. “He is one of the people I dedicated Messages of Hope to,” he added.

McClellan said he wants to use his success to give back to his community, which is why a portion of the proceeds from both his books will be donated to programs through Cathedral of Hope to help the homeless. And he also wants to continue to spread his message: Even in the darkest of hours, hope remains.

Messages of Hope and The Ant’s Palace are available wherever books are sold. They are available online at both Amazon and Barnes & Noble and by request at libraries and bookstores.