Partners in life and in business, Darryl Allara and Ken Freehill travel the world staging theatrical productions for the Army. And they have seen a difference since the end of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’

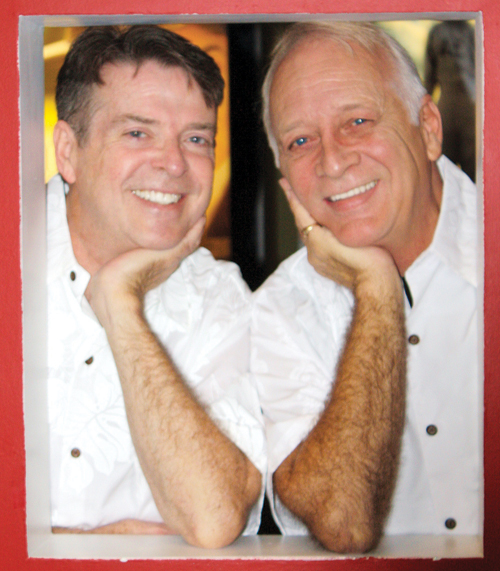

OUT ON BASE | Partners Ken Freehill and Darryl Allara have never hidden their sexual orientation or the fact that they are a couple from the military officials with whom they work. But the repeal of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ has made things less tense in many military communities, they say. (Photo Courtesy Darryl Allara and Ken Freehill)

David Webb | Contributing Writer

davidwaynewebb@yahoo.com

The end of “don’t ask, don’t tell” was a long time in coming — not only for the estimated 65,000 gays and lesbians serving in the U.S. Armed Services, but also for others engaged in little-known, supportive roles for active-duty personnel.

Dallas show business couple Darryl Allara and Ken Freehill, who tour the globe as civilian contractors for U.S. Army Entertainment, were as relieved as anyone else last fall when President Barack Obama officially recognized the end of the 18-year-old discriminatory policy. The life partners quietly cheered the Department of Defense memo released Sept. 20 lifting the ban on homosexuality, knowing it would provide a new sense of freedom for both them and the gay and lesbian soldiers they encounter on military installations.

“I think that in the communities we’ve been in, things are less tense,” said Freehill during an interview at their East Dallas home recently while the couple took a holiday break from 202 days on the road in 2011.

“I think maybe those people in the past who may have felt reluctant to talk to us now feel more comfortable in approaching us,” he added.

At the military installations Allara and Freehill visit, there are ample opportunities for one-on-one conversations with soldiers. Both men are judges for the U.S. Army’s Festival of Arts, and in a separate contractual project they stage Murder 101, an interactive comedy tailored to each base using soldiers and their family members and base civilian employees as actors.

“When we walk into a room, there is so much enthusiasm from everyone,” said Freehill, who has 30 years of experience as a director, producer, writer and actor and currently performs in one-man plays locally.

In staging the murder mystery dinner theater productions, the couple meets with volunteers who are interested in performing, assigns them roles, conducts rehearsals, markets the production, directs the shows and appears in the performances — all in one week’s time. It’s a challenging task with a taxing schedule that they’ve mastered and carried out for 10 years now.

“We’ve been very mission-oriented, bringing theater to where it doesn’t exist,” said Allara, who received a U.S. Army scholarship that led to a degree in theatrical producing and directing after he ended a tour as a medic in Vietnam in 1969.

“By the time the week is over it looks like we’ve been working with them for a month,” Allara said.

Before the ban was lifted, it was a complex situation for Allara and Freehill, who in their roles entertaining, training and evaluating soldiers and their families weren’t subject to the provisions of the military prohibition on being openly gay. They wanted to be honest about themselves, yet not detract from the mission of their work.

“I did feel the policy had to be respected, because we never wanted to put a soldier in an awkward position, and we never wanted to cause anyone to be uncomfortable,” Allara said. “Our whole mission is to bring joy to everyone.”

Even so, the couple knew people would figure out they weren’t the rank-and-file type of civilian workers that soldiers expect to see on military bases, Allara noted.

“We have never encountered overt discrimination,” Allara said. “By the same token, we have never hidden who we are. It’s not a subject we initiate, but we’ve had soldiers talk to us about it.”

Freehill said that during 2011 while the Pentagon implemented the repeal of DADT and conducted related training for military personnel the couple traveled to 37 military installations for 50 events on three continents. They completed their work without experiencing any of the types of discriminatory incidents many naysayers warned would happen in the military if Congress lifted the ban, he said.

“People figure out in short order we’re a couple, and not just a theatrical partnership,” said Freehill, who points out they have been a couple for 32 years. “They see us together. We don’t make a big deal out of it. But they aren’t dumb.”

Freehill said they have always been careful not to give anyone the wrong impression.

“We are not on the make, and we don’t give that vibe off,” Freehill said. “Everyone feels secure. We are never alone with anyone.”

Allara said his experiences with the military have, for the most part, always been positive and no more discriminatory than in any other walk of life.

As a helicopter medic in Vietnam, he got his first taste of show business when he produced theatrical shows for fellow soldiers using what he had learned at a base playhouse during basic training at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio.

“For lack of a better word it was a M*A*S*H unit, and I was my unit’s Radar O’Reilly,” said Allara, who noted he “screamed all the way” when he was forced to abandon his company clerk duties and fly in the helicopters to combat zones.

Allara said that deplorable conditions in Vietnam inspired him to take on the staging of a show and probably encouraged fellow soldiers to welcome it.

For one show he requisitioned six jeeps and drivers for the use of their headlights in a theatrical production. A stage was fashioned out of an old flatbed truck.

“We had a terrible morale problem,” Allara said. “We were looking for diversion. We needed to find a way to bond everyone together.”

Rather than getting court-martialed for the jeep stunt as he feared might happen, Allara’s amateur shows, including Sorry Wrong Number, brought him praise and requests for productions at other locations, including a production of Stop the World; I Want to Get Off.

Those efforts eventually led to his Army-sponsored scholarship to theatrical school in San Diego.

Allara said it is ironic that his theatrical work in the Army led to his lifelong career because he had no interest in theater in high school. The U.S. military has sponsored entertainment programs for personnel since World War II, and most bases had theatrical playhouses before television viewing became the most popular form of entertainment.

“When I was drafted I had no thoughts about theater at all,” Allara said. “I was picked on as a kid, and standing in front of people performing was the last thing I wanted to do.”

Later, Allara attended graduate school at the University of Arizona where Freehill was an undergraduate, but they never met. Oddly, they discovered later they had participated on a theatrical production at the same time, and they have a playbill with both of their names listed to verify it.

The couple later met in Los Angeles on a theatrical production and became lovers. For a while they operated a show business school together before relocating to Dallas, where Freehill took a job as executive director for the Screen Actors Guild.

It was about that time 17 years ago when Allara resumed his association with the military, accepting a job as a traveling second judge for the Army Festival of the Arts, a 40-year-old organization. The senior judge for the organization with whom Allara worked on a Bicentennial show in 1976 sought him out for the position.

“You meet people in life,” Allara said. “They go out of your life and then they come back.”

When about five years later the senior judge retired, Allara knew he didn’t have to look far for a new second judge. The Screen Actors Guild had relocated from Dallas to another city, leaving Freehill without a job.

So he joined the Army, too, so to speak.

About 10 years ago Allara and Freehill began staging their murder mystery productions for the Army. They first had designed and produced the mystery shows in Los Angeles, and they tried them out on military audiences with success.

An early production took place in Fort Campbell, Ky., where they still command great respect from base officials, volunteers and audiences, according to Linda Howle, director of the base recreation center.

“They are amazing, and they are fantastic,” said Howle in a telephone interview. “They are very creative. Every time I have them here they do a wonderful job, and when they come back it is always an even better performance.”

Allara said one of the reasons that he and Freehill enjoy so much respect from military officials is that they have a reputation for making sure the show will go on, no matter what. Their sexual orientation seems to have mattered little, if any at all, to Army officials in charge of military entertainment.

“They know they have two theater specialists they can send anywhere in the world,” Allara said.

About 15 years ago, Allara said, he met with a commanding officer who wanted to hire him, and he told the official about his relationship with Freehill.

“I knew they were rounding up soldiers and prosecuting them,” Allara said. “I told him I didn’t want it to bite him in the ass later. He thanked me for telling him.”

Allara said one of the reasons he and Freehill work together well as a romantic and a professional couple is that it is also economically advantageous to them. The Army pays them a flat fee for their work, from which all expenses must be deducted, and the arrangement of staying together on trips allows them to save money.

“We are able to keep rates really low for the Army because we share accommodations,” Allara said.

Fees for Allara’s and Freehill’s contracts come from discretionary funds raised by the Army from ticket sales and other enterprise activity, not from tax dollars, according to the show business couple.

The couple said the only hint of discrimination they ever felt during their travels for the military was when hotel staff asked if they wouldn’t prefer separate beds or rooms. Although they’ve never lost a military contract because of their sexual orientation, they did lose a couple in Los Angeles years ago because of it, they said.

“Discrimination is everywhere,” Allara said. “It doesn’t have to be in the military.”

Allara said that as a combat veteran he sees the greatest benefit of the new policy to gay and lesbian soldiers to be the security of being part or a team, not the advantage of freedom of expression and social acceptance.

“They now will be able to serve their country without worrying about their backs in addition to the enemy in front of them,” Allara said.

For Allara and Freehill, life will continue much as it has for the past decade, together night and day except for when they are out of town on separate judging assignments. It seems natural to wonder whether they might enjoy the occasional break from each other’s company, but that is apparently not the case.

“It’s lonely,” Freehill said. “I admit it. We usually can’t wait to get home to be in each other’s company.”

Allara said that they often debate many subjects related to their work, but they always agree on how they feel about returning home to the company of the best audience anyone could have — the three dogs they rescued.

“It’s like dying and going to heaven for us,” Allara said.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 13, 2012.