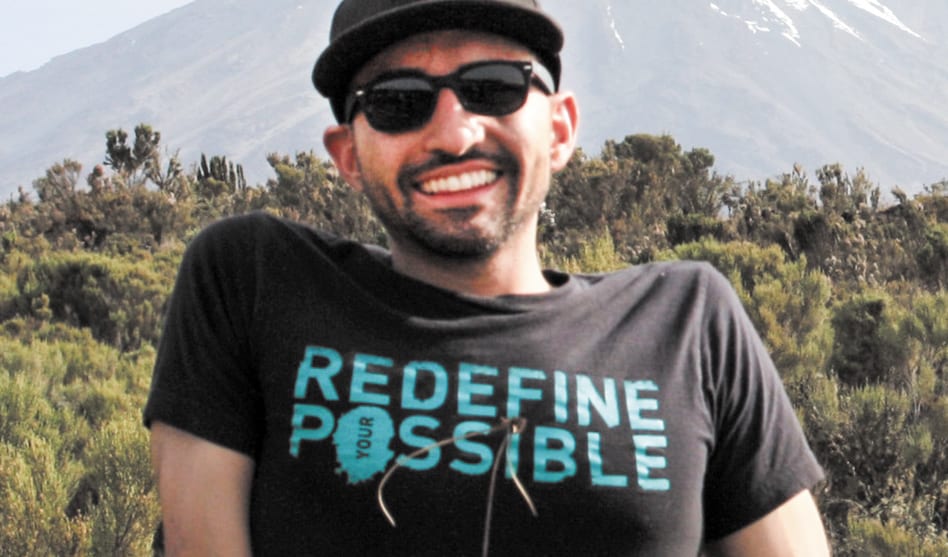

Spencer West, who climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, tells young people they can rise above their challenges.

From a genetic disorder that took his legs, to his work as a social activist, Spencer West defies limitations

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

nash@dallasvoice.com

You might think that being born with a genetic disease that kept his muscles from working properly and that forced doctors to surgically remove his lower extremities — from the pelvis down — by the time he was 5 would present enough challenges for any one person.

But for Spencer West, coming to terms with his sexuality proved to be even more difficult.

West — a motivational speaker and social activist who works for WE, an organization that works to “empower people to transform local and global communities by shifting from ‘me’ thinking to ‘we’ acting” — had his lower legs amputated at the knee before he was 5 years old. Doctors had hoped that would be enough to contain the damage from sacral agenesis, the condition with which he was born, and that he could eventually be fitted with prosthetic legs. But when he was 5, doctors had to remove the rest of his legs, from the pelvis down.

“After that surgery, I was told I would never sit up or walk, that I would probably never be a functioning member of society,” West said in a recent interview. “But my parents never believed that. They were amazing. They never treated me differently, and I legitimately never realized I was different until I went out in public.”

“After that surgery, I was told I would never sit up or walk, that I would probably never be a functioning member of society,” West said in a recent interview. “But my parents never believed that. They were amazing. They never treated me differently, and I legitimately never realized I was different until I went out in public.”

West said that his parents always wanted him to be as independent as possible, “just in case something ever happened to them. They wanted me to be able to take care of myself. So they forced me to take the risks I had to take to be independent.

“I did all the things normal kids would do,” he continued. “I took gymnastics, swimming lessons. I went to kindergarten and on to public school and then college. I had a normal life.”

Except that West always knew he was “different” — and not because he had no legs.

“To be honest, being gay was much harder” than dealing with his physical limitations.

“When they removed my legs, which were useless, suddenly I was able to get around much better. My legs weren’t in the way any more. I struggled much more with the idea of being gay.”

West said he was a senior in high school in Rock Springs, Wyo., when Matthew Shepherd was murdered in a highly-publicized anti-gay hate crime in Laramie. “That happened just four hours away from my hometown,” West recalled. “Suddenly, the world was not a safe place at all for gay people. I told myself, there’s no way I could be [gay] — not if being gay meant I could be murdered right there where I lived just because of who I was.”

West said he was a senior in high school in Rock Springs, Wyo., when Matthew Shepherd was murdered in a highly-publicized anti-gay hate crime in Laramie. “That happened just four hours away from my hometown,” West recalled. “Suddenly, the world was not a safe place at all for gay people. I told myself, there’s no way I could be [gay] — not if being gay meant I could be murdered right there where I lived just because of who I was.”

It wasn’t until he went away to college — at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah — that West began to realize that there was so much more to being gay than what he knew.

That’s when he began his coming out process, first telling his best friend and then calling his parents. And again, he said, his parents “were amazing.”

“They immediately said, we love you and we support you. For my mom, it took about a year of discussion, but not because she didn’t accept me. It was more that she wanted to understand what I went through. Like, ‘I think we always knew, but you said you weren’t, so we believed you.’ But they always responded with acceptance and love, right from the beginning.”

After getting his degree in communications at Westminster, West said he couldn’t find a job in that field, so he moved to Phoenix and took a job as operations director for a company. “I chased the American dream of money and a good job,” he said. “But it didn’t bring me the happiness I had expected it to.”

And then, in March of 2008, he went with friends on a volunteer trip to Kenya, and “Everything changed,” he said. “I was so enamored by the work they were doing, breaking the cycle of poverty overseas and empowering youth there.”

The trip was sponsored by WE, an organization that organizes groups for “meaningful travel,” through which participants have a chance to be “a part of something larger than [themselves],” and to be “immersed in a new culture, fostering genuine connections and seeing the world through a new lens.”

Particpants “Work alongside community members on a sustainable development project and witness firsthand how communities are coming together to help break the cycle of poverty,” according to the WE.org website.

West was so taken with the organization and its work that he applied for a job with the organization and then moved to Toronto where WE is headquartered. He now works as a motivational speaker and leadership facilitator, helping organize volunteer trips to Kenya, Tanzania and India, and facilitating interactions between the local residents and the visitors — things like going with the women of a village to get water, helping build a school, touring markets and other cultural activities.

“I talk to people about how they get involved,” he said. “The trips are usually about 10 days, depending on the location.”

WE offers school and youth trips for those ages 13 and up over spring break and during the summer, and corporate and family trips for all ages, year-round. West also speaks at WE Day youth empowerment events for young people around Canada and the U.S. The organization recently held its first WE Day Texas event, at the Curtis Culwell Center in Garland.

He is also known for having summited Mount Kilimanjaro on his hands and in his wheelchair, raising funds to help provide clean water to more than 12,500 people for life, and for having completed a 187-mile trek on his hands and in his wheelchair from Edmonton to Calgary.

People who hear him speak, he said, usually look at him and realize that no obstacle is truly insurmountable. “We all face some sort of challenge. Mine is physical, and you can see it. But we all have challenges. WE has helped 200,000 kids around the country realize they all have the ability to give back.”

While speaking at WE events, West said he tends to focus on using his own physical limitations to say, “Yes, I am different. But I am worthy, and I provide value, and each of you can, too. We are all different, and that’s what makes us lovely, and we can use those things that make us different to give back in our own ways.”

But he also wants to address the LGBT community, too, and, he said, he has begun “using social media as a way to talk more deeply on LGBT issues. … I am slowly learning how to insert myself as an activist, because I have always focused so much on breaking the cycle of poverty through my work at WE. In 2015, I came out publicly and told my story at New York Pride. I have put my coming out story on YouTube. Now I am just figuring out what to do next.”