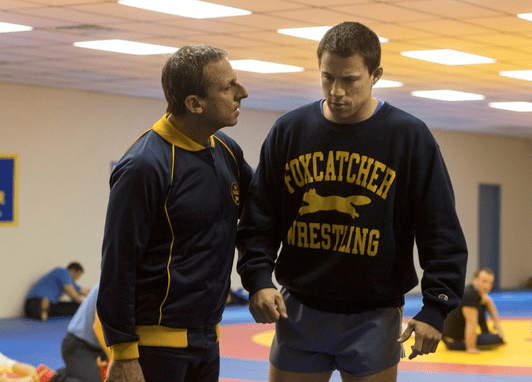

Carell and Tatum

Bennett Miller has only directed a handful of feature films: Capote, the stark, ominous true-crime story behind gay author Truman Capote’s efforts to write his masterpiece, In Cold Blood; and Moneyball, about A’s manager Billy Bean’s formula for for turning a last-place ball club into pennant champs. Combine the catchwords of both those films: True-life, gay, sports, crime, murder, even one-word title … all elements that emerge, in various levels, in Miller’s newest effort, Foxcatcher. It could — should? — be the perfect confluence of topic and talent. But while there’s no denying the craftsmanship and sincerity that goes into the film, it’s also difficult to shake the sense that there isn’t enough undergirding its tone, its artistry, its seriousness.

The film is based on actual events that, while shocking at the time, haven’t lived on in popular culture like they might have. Olympic wrestler Mark Schultz (Channing Tatum) hasn’t lived well off the glory of a gold medal, remaining in the shadow of his more legendary older brother David (Mark Ruffalo). Then one day the eccentric billionaire John DuPont (Steve Carell) calls on him: How would Mark like to join Du Pont and his band of merry athletes at his Foxcatcher estate to train for the next Olympics? Du Pont fancies himself a world-class coach and sports benefactor — equal parts Bela Karolyi, Vince Lombardi and Tex Schramm, but it’s apparent to everyone but him he’s merely a world-class creep. Du Pont — remote, humorless, socially awkward, patently sexually repressed and lacking in any self-awareness — is a professional dilettante, a dabbler who has found the homoerotic world of pro wrestling as a weird outlet for his need for masculine physical contact. He writes laudatory speeches about himself for others to deliver. He creates a seniors wrestling league so that he might win a trophy. He commissions a documentary about himself and dictates the outcome. (It is not, in the world of the film, totally his fault. He is part of a profoundly disconnected family that has a history of making documentaries about themselves. The rich really are different from you and me.)

Tatum and Ruffalo

You know — both because pre-opening press mentions it, and the tone of the film practically projects its ominous outcome from get-go — that Du Pont is a brittle twig who will snap and commit a seemingly senseless act of violence, a crime made more tragic because of its pointlessness. You hope that the goal of the movie will be to provide context — to frame the crime and make it seem less random than inevitable. You want to, if not assign blame, figure out not just what happened by why.

And that’s where Foxcatcher fails. Indeed, it never even comes close.

There are many images and a spooky vibe that linger after the film ends, but what you never get is a sense of purpose. Miller has made a haunting story that doesn’t haunt you, a tragedy with no flawed protagonist to sympathize for. The film, like John Du Pont, is a cypher.

Miller has allowed all the artists involved so much latitude to create that he seems to have forgotten his role is to unite them together. I venture to guess that half the below-the-line budget was spent on singlets, nose putty and false teeth: Carell, Tatum and Ruffalo are all made the physically transform for their roles, getting seemingly lost in the characters, the way Philip Seymour Hoffman did in Capote. But Hoffman had a deceiver’s heart at work behind the scenes; you could tell what he was thinking. Carell is a wall of unfathomable mystery, like the patients in the criminally-insane wards of bad horror movies. You can’t understand him, just observe him. All of which keeps everything perpetually on the surface.

The actors are all quite good at their impersonations: Tatum is lurching and damaged, and you feel for him as an inarticulate man daring to find a form of expression that makes sense to him; Ruffalo’s big-brother pal-ness feels lived in, his accent authentic; and Carell is sometimes so strange that it gives you gooseflesh. But their characters, like the pacing and tone of the film, never alter. Miller’s preoccupation with silences and stillness begins to feel like a cheat, a substitute for figuring out these characters and really providing insight. (The horrible events for which the entire incident is remembered occur in the final minutes of the film, with only a few post-script paragraphs to inform us of what eventually happened. Wikipedia is more informative.)

Foxcatcher has a distinct European air to it, not unlike Capote, but without the passion that European films usually find simmering beneath. It’s OK to be cold, but to make the audience care, there has to be a spark of humanity. This film never generates that kind of heat.

Two and half stars. Now playing.