I’ll just say it: I don’t know what modern opera composers have against a melody. Perhaps it’s the anxiety of influence that no one can write an aria as beautiful as “Nessun Dorma” or as catchy as “La donna e mobile” or harmonies as tight as Lakme‘s “Flower Duet.” I don’t care. I like a good song. (I think opera composers are afraid of sounding too much like Broadway.)

I’ll just say it: I don’t know what modern opera composers have against a melody. Perhaps it’s the anxiety of influence that no one can write an aria as beautiful as “Nessun Dorma” or as catchy as “La donna e mobile” or harmonies as tight as Lakme‘s “Flower Duet.” I don’t care. I like a good song. (I think opera composers are afraid of sounding too much like Broadway.)

There are no hummable arias in Everest, composer Joby Talbot and librettist Gene Scheer’s one-act opera that received its world premiere from the Dallas Opera this weekend. That is practically the only criticism I have of this piece, a breathtakingly powerful and phenomenally well-staged achievement that lingers in your mind and your heart.

Based on the events of the ill-fated 1996 expedition to summit Everest (recounted by John Krakauer is his compulsively thrilling first-hand account Into Thin Air) it focuses on three climbers — Rob Hall (tenor Andrew Bidlack), the expedition leader, and two clients, Doug Hansen (baritone Craig Verm) and Dallasite Beck Weathers (bass Kevin Burdette) — who become trapped while descending from the Hillary Step during a massive blizzard and suffer exposure, eventually leading to the deaths of two of them (in reality, a total of eight people lost their lives during the climb).

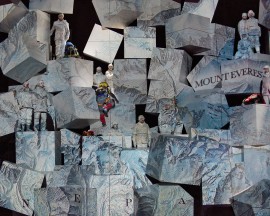

Unlike a play like K2, however, Scheer doesn’t confine the action to the South Face of the mountain; through a series of flashbacks and phone calls, we interact with Hall, Hansen and Weathers’ families, discovering insights into what motivated them to pursue this costly, time-consuming and dangerous activity. None of this would be possible without Rob Brill’s awe-striking set design (a series of about 70 white cubes that fill the Winspear stage), Elaine J. McCarthy’s evocative projections and director Leonard Foglia’s inventive staging, which creates a dreamy but visceral landscape. (The listing of the names of all those who have perished on the mountain, and Weathers’ crawl to safety having been left for dead, will send chilblains through you.)

Despite the absence of vocal melodies, Talbot’s score is a driving force, which starts out as a collection of stabs of white noise and transitions into a pulsing underscore, reminiscent of an action film, deftly modulated by conductor Nicole Paiement. The use of the opera chorus to portray a kind of ghostly voices of the dead doesn’t quite register at first, and the tune and lyrics are too strident and disconcerting, but their haunting presence throughout adds a paradoxical mood of dread and comfort to the proceedings.

Bidlack’s performance as Rob Hall is achingly adept, and his duets with mezzo Sasha Cooke as his wife Jan are tender and and heartfelt. They are the standouts, though both Verm and Burdette provide evidence that great opera is as much about fine acting as it is singing.

There are only two more performances of Everest — tonight and Saturday — so you should see it if you can. But I wouldn’t worry too much; this is destined to become a part of the modern canon, one of the most compelling and relevant operas in a generation.

There are only two more performances of Everest — tonight and Saturday — so you should see it if you can. But I wouldn’t worry too much; this is destined to become a part of the modern canon, one of the most compelling and relevant operas in a generation.

The presentation by the Dallas Opera opens with Act 4 of the clunky Catalani opera La Wally, also set on a mountaintop. It’s not a major work by any standard, despite the fairly memorable aria “Ebben? Ne andro lontana” (which, incidentally, is a fine melody for singing!). But this piece is an excellent showcase for Mary Elizabeth Williams (a replacement for Latonia Moore), whose stunning rendition of the piece — and her impressive domination of the entire 30-minute performance (she gets limited assistance from the bland Rodrigo Gariciarroyo) — shows that there’s still some hunt in this dog. Also credit director Candace Evens for a creative staging of the famed avalanche and maximum use of a minimal set. It really does a fine job of whetting your appetite for the main course that follows.

Get tickets here; check out a slideshow of Karen Almond’s photos from Everest below.