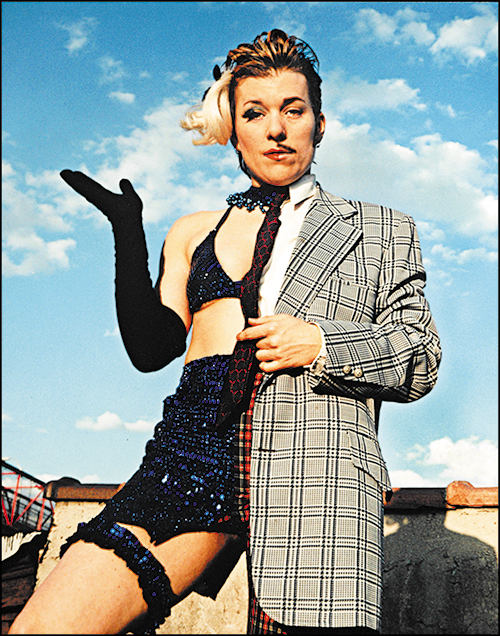

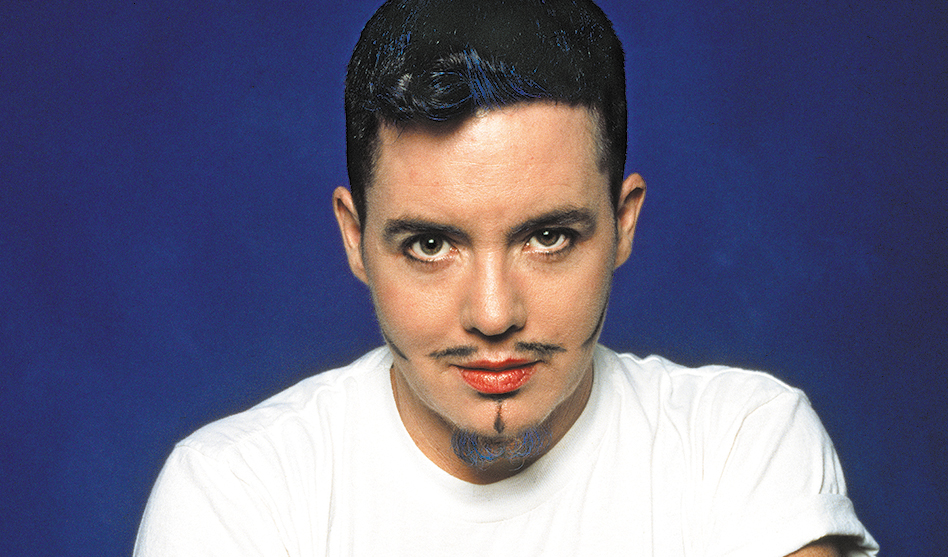

Del LaGrace Volcan’s “Self-Portrait With Bluebeard, larger image below, and Volcano’s photo “Mo B Dick, Half & Half, smaller image below. (Photos courtesy of Del LaGrace Volcano)

Del LaGrace Volcano’s The Drag King Book that they co-authored with Jack Halberstam changed my life. Not only was it the first (it was published in 1999) and only book of its kind, but it was the impetus and inspiration behind my desire to create an all-inclusive queer home and a body of work for female drag queens.

Del LaGrace Volcano’s The Drag King Book that they co-authored with Jack Halberstam changed my life. Not only was it the first (it was published in 1999) and only book of its kind, but it was the impetus and inspiration behind my desire to create an all-inclusive queer home and a body of work for female drag queens.

In fact, the majority of Volcano’s work has had a huge impact on my queer formative years.

Their fifth book — co-authored with Ulrika Dahl — Femmes of Power: Exploding Queer Feminities along with its many essays, specifically “Copies without Originals: On Femme Drag,” was the first time I saw my complete queer self — identity and performance — anywhere EVER.

Their 1998 “Half and Half” photograph of Mo B Dick is a time-stamp and reminder to us all even now, especially now, to never forget the subversiveness of drag, the political nature of art.

The beauty of Volcano’s work is that without even knowing it, their work foreshadowed, not to mention helped, usher in all the conversations, art and movements we are now openly having about gender, gender binaries/dichotomies and living in the spaces between.

The beauty of Volcano’s work is that without even knowing it, their work foreshadowed, not to mention helped, usher in all the conversations, art and movements we are now openly having about gender, gender binaries/dichotomies and living in the spaces between.

Much like the first queer creative I profiled for this series, Gloria Anzaldúa, Volcano’s work has always existed and is most comfortable in what Anzaldúa referred to as the nepantla, the spaces in-between.

Del LaGrace Volcano was born intersex in 1957 in California. They were raised female from birth and made female their chosen perceived gender for 37 years. It was fear of adequacy that tethered Volcano to the gender binary for so long, a point on which they reflect in a 2019 interview with The Guardian. “I was in a liminal state with my gender: I was moving from being perceived as female to being perceived as male, but really I was coming to terms with the fact I was born intersex,” they said.

It was in this crux of attempting to understand themselves that birthed Volcano’s most culturally queer-significant self-portrait — “Self-Portrait With Bluebeard,” which queers gender in a subtle yet striking way. The juxtaposition of Volcano’s perceived masculinity, the facial expression and the blue mascara on both their hair and beard screams of the gender-queerness and fluidness that would, more than two decades later, become major topics in and outside of our LGBTQ community.

That is what makes it completely groundbreaking, as groundbreaking as the ideology behind it, especially considering the time period in which it arose.

Volcano didn’t see themself as going from one gender to another; they didn’t see themself as transitioning. In that same The Guardian article, Volcano is quick to point this detail, saying, “I had no interest in moving from one fixed point to another.” Instead it was at that moment documented, captured forever in a photographic memory that they decided to live outside the gender-binary.

When I asked Volcano what inspired their work back then and what inspires it now, they explained, “What inspired me back then is exactly what inspires me now: LIFE; my life and the people who populate it. Connecting deeply with others, through the medium of photography, is something I not only enjoy and am good at, but something I need to do for my mental, emotional, physical and spiritual health.”

It is their desire for deep connection and art not only as a political act but also as a way to heal the self that can also be seen threading throughout their work that draws me and many others to Volcano’s work.

One of my favorite things that Volcano has ever written further expresses their desire for connection and inclusivity and can be found on their Facebook fan page: “I believe in crossing the line. Not just once, but as many times as it takes to build a bridge we can all cross together.”

Together.

That’s the spirit that makes Volcano’s work so fascinating — the spirit of leaving none of us behind. By being a voice of the least-represented people in our queersphere, it is inclusive of us all.

As someone who has influenced my epistemology as a queer artist, when the opportunity arose for me to ask them what their number-one piece of advice would be for emerging queer artists, I took it.

They answered, “My number-one piece of advice for any queer person who wants to make art is to just do it. If you are afraid to do it, do it anyway.

“That requires courage, and you if cannot locate your courage, then either do some work on yourself so you can, or do something else.”

They added, “Being an artist is something you do because you are compelled to make work, not because it will make you famous or rich. I’ve been making queer work for over 40 years, and just this month I have finally been funded! If you make political work that challenges the status quo don’t expect to be financially rewarded.”

The point, as I’m sure Volcano would agree, is to make art from your life that has the potential to change people’s lives.

And to, hopefully, change your own.

Lovely article with only one error! Femmes of Power: Exploding Queer Femininities (with Ulrika Dahl) was my fifth book, not my second!

Thanks for the heads up. That has been corrected