This startling exhibit opens the third floor Holocaust Wing of the new Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

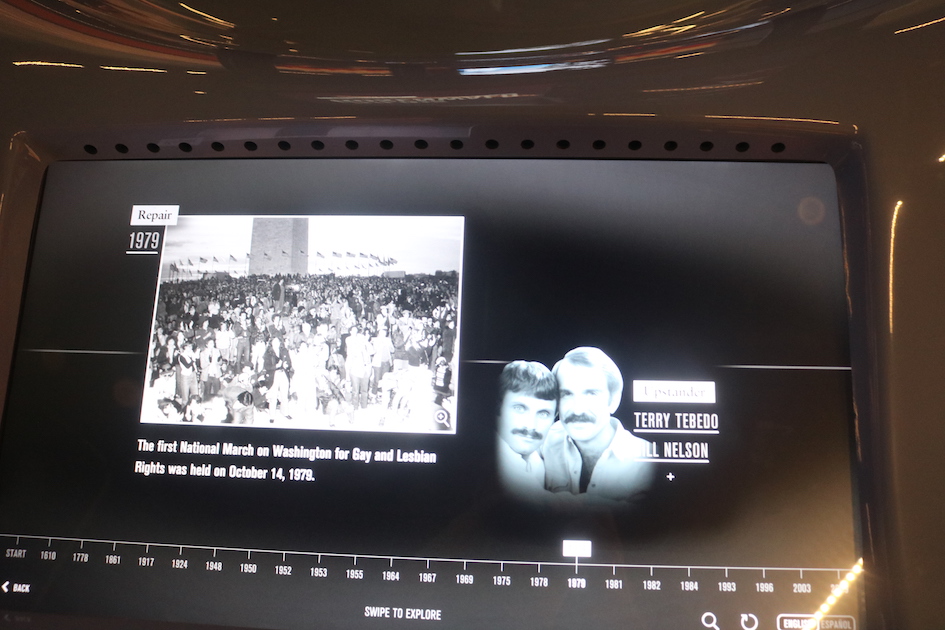

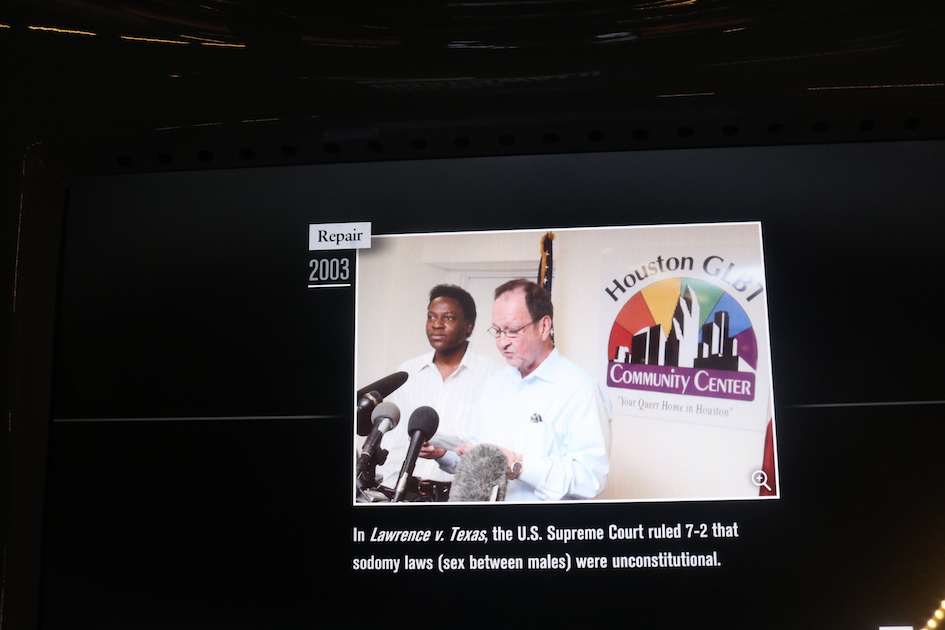

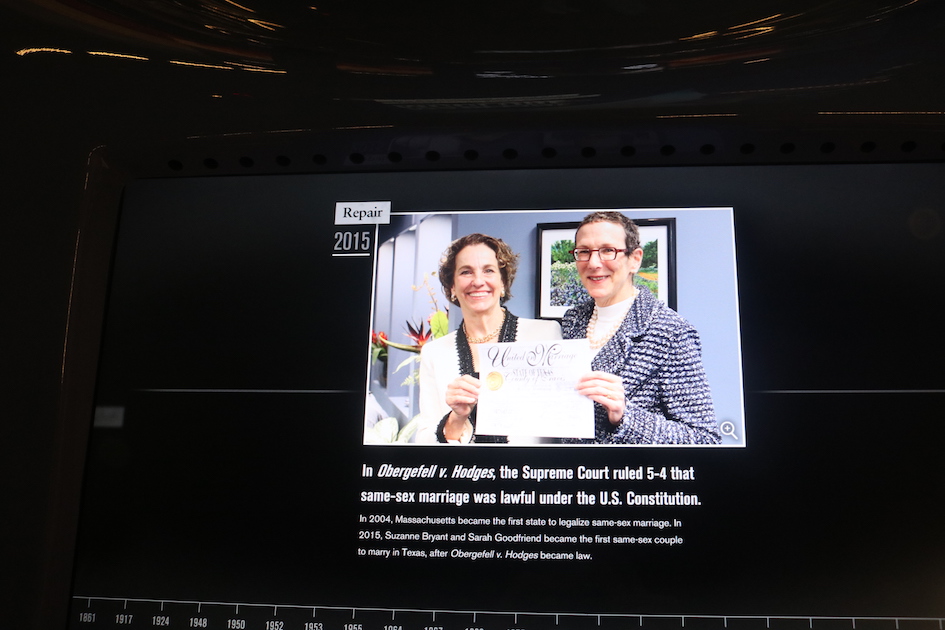

Few if any other Holocaust museums include LGBT human rights in their permanent exhibits. But in Dallas’ Holocaust museum, both local and national figures — Harvey Milk nationally and John Thomas locally — are part of the exhibit. So are Bill Nelson and Terry Tebedo, the couple for whom the HIV clinic on Cedar Springs Road is named. Lawrence v. Texas, the case that invalidated section 21.06 of the Texas penal code that made same-sex relationships illegal, is featured, and so is Resource Center.

The new Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum on Houston Street at Pacific Avenue (along the DART tracks) opens to the public on Wednesday, Sept. 18. “At a time when our country is being attacked from within, our museum is critically needed,” said Mary Pat Higgins, CEO of the museum.

The museum uses cutting edge technology. For its hologram theater, Holocaust survivor Max Glauben, 91, recorded 20 hours of usable footage. Ask Max a question and his hologram (or maybe it’s the technology linked to producing the hologram) quickly searches for the right response and answers the question. And if you’re lucky as I was, the real Max will be on hand in the museum to interact playfully with his holographic self and answer additional questions from the audience.

Mayor Eric Johnson told reporters at a press conference at the museum, “My dream for Dallas will be a city of upstanders.” He said the museum would inspire all of its visitors to stand up for what’s right and to fight intolerance. “There’s no place for hatred in Dallas,” he said.

Johnson said he was proud that one of his first official acts was to open the new museum. He will make remarks again at the public opening on Wednesday, Sept. 18 at 9:30 a.m.

The new special exhibits area alone is about half the size of the old Holocaust Museum across the street. The first special exhibit focuses on what people took with them when fleeing a genocide. A particularly powerful piece is a dress a mother found that belonged to her daughter who was killed in the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

An upcoming special exhibit next year will feature Stonewall. That’s not surprising because at the former museum, the highest attendance for a special exhibit in its 15-year history was Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945 that Congregation Beth El Binah sponsored with a number of LGBT community organizations and individuals.

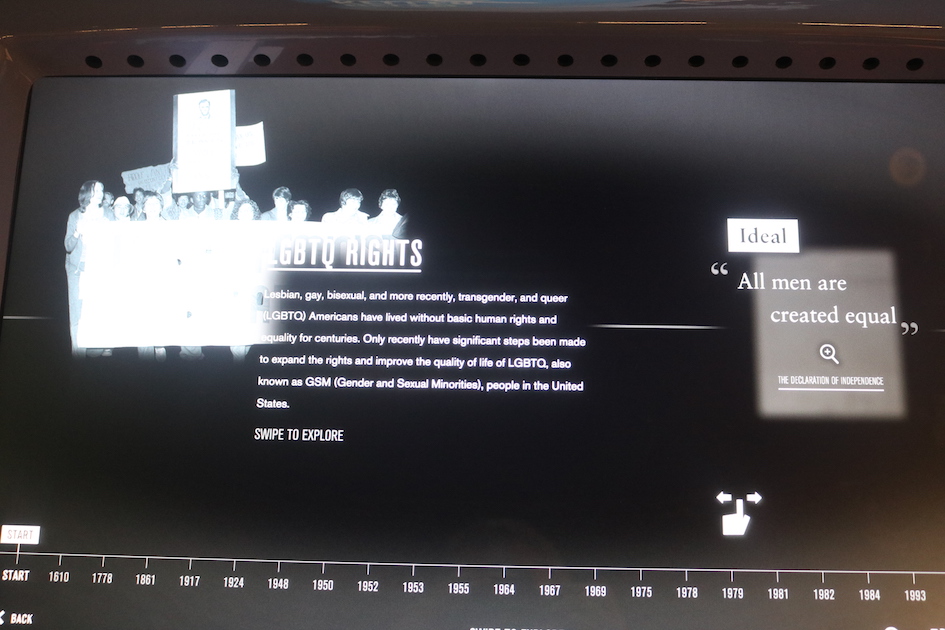

The LGBT exhibit is part of the Pivot to America Wing. After exhibits on the Holocaust and then on genocides around the world, this final exhibit explores the civil rights movement and human rights for immigrants, Native Americans, religious rights, women’s rights and more.

According to Higgins, she’s interested in bringing in speakers to talk about the exhibits in the Pivot to America Wing including the history of LGBT rights in Dallas and the U.S.

Graphics help illustrate the history throughout the museum. One museum official, pointing to a map of Europe highlighted with pins representing concentration camps, asked how many camps there were. She said most people guess six or seven. Those were the death camps. In all, there were 43,000 camps across the continent that held 20 or more people.

An exhibit carried over from the old museum is made of 13 cement pillars. The relative height of each represents how many people were killed each year from 1933 to 1945.

The museum’s design includes quite a bit of symbolism. The copper roof has already begun to oxidize. Within a year and a half it will become dark brown and from there develop a green patina. That oxidized exterior helps keep the interior metal strong and represents the resilience of those who survived the Holocaust as well as other genocides and those who fight for human rights for everyone.

A sculpture in the garden by James Searles consists of 18 flowers each with six petals. Each of the petals represents a million Jews killed in the Holocaust. But in Hebrew, the word “chai” means both life and is the number 18. So the 18 flowers represent life while remembering the 6 million who died.

The museum is designed to welcome 200,000 visitors each year. About half of those are students who will learn about the effect of hatred and bigotry and be encouraged to be upstanders — people who stand up to those behaviors — and not be bystanders.

— David Taffet

This is truly progress for all. I am so happy to be a witness.