A gay son at his straight father’s passing

On Sunday, Jan. 13, 2019, at around 1:20 p.m, Lynell Spiller, the man responsible for co-creating me, made his transition into infinity. His passing wasn’t unexpected, because near the end he had simply given up; he had a massive stroke the day after Thanksgiving 2018, and he wanted to go.

On Sunday, Jan. 13, 2019, at around 1:20 p.m, Lynell Spiller, the man responsible for co-creating me, made his transition into infinity. His passing wasn’t unexpected, because near the end he had simply given up; he had a massive stroke the day after Thanksgiving 2018, and he wanted to go.

Unlike others who share the news with others of a parent’s passing on social media, often with glowing remembrances and profound sorrow, I chose to remain silent until I had time to process what his death meant to me, and what my response would be.

I did inform a small number of people, but for the most part I kept the information private until now.

Despite being given his first name as my middle name at birth, we were not close. In fact, when he died, I had not seen him physically in three decades, and I had not spoken to him in more than 15 years. I had no real emotional attachment to or fond memories of him. So when my family was faced with his imminent death, I had some decisions to make — decisions I have thought about occasionally over the years.

Primarily, I had to decide whether I would even make the trip to Connecticut where he lived to see him for the last time or to attend his funeral, as I knew would be expected to do. As harsh as it may sound — and despite him being a responsible parent and providing for my needs from birth until the time I left home for college at age 17 — from an emotional standpoint he felt more like a sperm donor to me than anything else, if I am to be honest.

So when I received a call from my brother a week before Lynell’s transition, letting me know Lynell may be on his way out of here, I literally had to make what seemed like a split-second decision about whether I would attempt to see him.

Finances weren’t an issue; my husband works for a major airline carrier, and I can fly free anywhere in the domestic U.S. and overseas.

Finances weren’t an issue; my husband works for a major airline carrier, and I can fly free anywhere in the domestic U.S. and overseas.

The real issue was whether I had the will to confront the past, our personal history, and make the trip despite what my heart was telling me.

From the moment he realized his son was not like other boys, my father had a problem with my sexual orientation. I vividly remember walking in on him talking to someone on our wall phone (he didn’t know I was in the bathroom behind him) and hearing him tell the person on the other end of the line that he wished I had never been born. That created distance in our relationship that lasted throughout the rest of his life.

But three hours after my brother called, I was on a plane headed to Connecticut, not certain what would unfold during the trip and how I would process it from a visceral standpoint. There were just a multitude of different tangibles and intangibles to consider.

I didn’t know what I might be facing, and that’s a position I hate being in. I want to be in control of all situations, a result of being a childhood victim of molestation and sexual assault.

My husband arranged for my youngest Spiller cousin — Torrie, who lives in Kentucky — to join me on the trip. She was more than happy to do so because my father was her favorite uncle. But there was more to it: She wanted a chance to say her final goodbye, but she also wanted to be there to serve as conciliator over the breakdown in mine and my father’s relationship, hoping she could help bring us together at his end.

I didn’t share that need. In my head, my presence was more about gratitude that he had given me life, even if my life has been hell, and showing respect for that.

I didn’t share that need. In my head, my presence was more about gratitude that he had given me life, even if my life has been hell, and showing respect for that.

Nothing more, nothing less.

When we arrived at the rehabilitation facility, Torrie initiated the reunion by asking him if he knew who she was. He did and joyfully asked her about her daughter, Gabby, his great-niece that he adored. Torrie then told him someone else was there with her, someone that had traveled really far to be with him, someone who was a male.

He was puzzled. He asked if it was my brother, and when she said no, he asked if it were each of my brother’s two sons. Torrie laughed and told him no. They lived nearby and so would not have had to travel far to be there. Confused, he again named my brother and his two sons, and again she told him no.

This visitor, Torrie told him, had come up from Dallas, Texas.

At that point, I interjected: “Lynell, you have TWO sons, and I am your oldest son. It’s Buster.”

He replied, “Who?”

I calmly answered, “It’s Buster.”

Using the side of his body not affected by the stroke, he leaned forward and looked at me with the little vision remaining in his left eye (he lost sight in his right eye in a car accident when I was growing up). He stared at me, and he kept staring, saying nothing.

Then he leaned back in his hospital bed and said, “I don’t know you.”

My cousin gasped a little, but I busted out laughing. Why? Because I didn’t know if he were being mean or trying to be sarcastic, or if it were a combination of both. Either way, it was funny as hell to me.

I moved closer to the hospital bed and with a resolve that he could not deny, even as he was approaching death, I said, “You may not want to acknowledge me, but I will ALWAYS be your oldest son.”

What would transpire during that visit and two others before he passed was a battle of wills — the old lion versus the not-so-much-younger lion.

Once when his nurses were trying to change him out of his jeans into more comfortable sweat pants, he was yelling and cursing up a storm about how they were hurting him. I stepped in and very firmly told him to calm down and let them to do their job. He wouldn’t relent, so I grew very impatient and said in a loud voice, “Lynell, STOP IT! Give me your legs and let me make them more comfortable so we can get these damn pants on!

He allowed me to straighten his legs out and calmed down noticeably. “Lynell, doesn’t that feel better now?” I asked, and he nodded.

I noticed his stroke-affected side looked really uncomfortable and motioned for Torrie to pass me two pillows. I told him I was going to prop him up in the bed with the pillows. When I was finished, I asked him, “Doesn’t that feel better?” Again, he nodded.

The next visit, he was still giving the nursing staff hell, particularly when they were trying to change his diaper. Despite how emaciated he was from the waist down, it was then I realized that we had the same body type, right down to shared age spots.\

Hmmmm.

As he cursed and yelled, I lost my patience again and told him forcefully, “Lynell, stop acting a damn fool and let them help you!” He balled up his good fist and retorted, “I will bop them and anyone else, including you!” I looked at him, steely-eyed, and said, “Old Man, you ain’t bopping no damn body! Hell, you can’t even get up from the bed.” He glanced at me and said, “Well, if I could, I would bop you all.”

In that moment, I realized I inherited a part of his temper and bravado.

Hmmmm.

What I said next surprised him — I even surprised myself — but I couldn’t contain it any longer: “Lynell, I don’t give a damn how bad you think you are, how much you cuss, or who you think you can bop. I cuss MUCH better than you ever could, and I have always been STRONGER than you. So again, let these people help you, and stop causing all this damn trouble!”

He grew silent then, and with Torrie on one side of the bed keeping him calm, the nurses and I were able to change his shitty diaper successfully. Then I washed my hands because some had gotten some of his waste on them.

The parent had become the child, and the child had become the parent.

I can’t fully put into words how humbling that was for me. I also realized in that moment that he and I were more alike than different, and that had I been born heterosexual, we probably would have had a great father-son relationship.

During our last visit the following morning, before I left for the airport to return home to my own life, I looked at him with that same degree of gratitude for his role in bringing me here that I had felt before, but also more compassion — more than I had realized I possessed — for what he was going through.

He was a great father to my siblings, a loving sibling to his own brothers and sisters, and a favorite uncle to many of my cousins. But he was not the best father to me or the best husband to my mother (they filed for divorce a month after I arrived in Texas for college).

But he was an EXCELLENT provider, as was my mother. And as I reflect more intimately on his life and the lessons he passed down to me — not related to the sexual orientation issue — I have to acknowledge that as a black man in that time period, he did the very best with what he had.

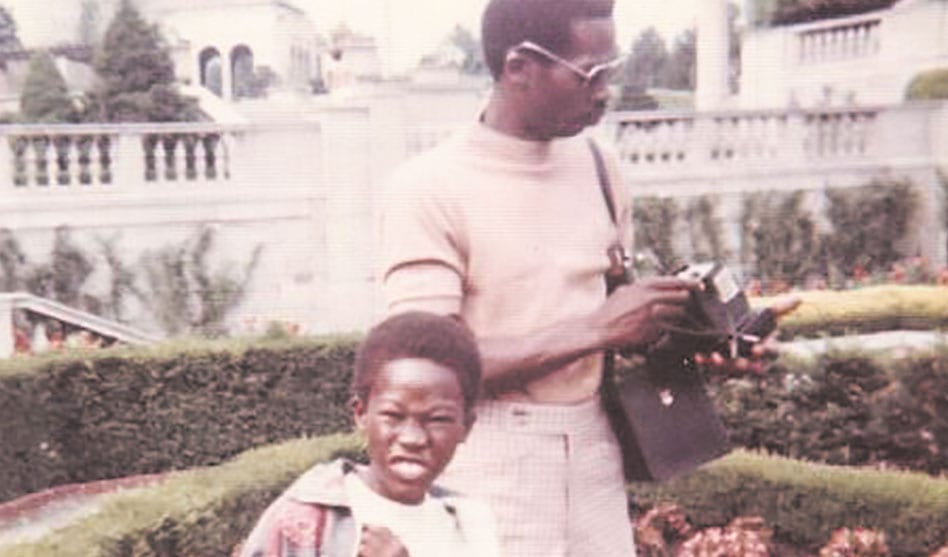

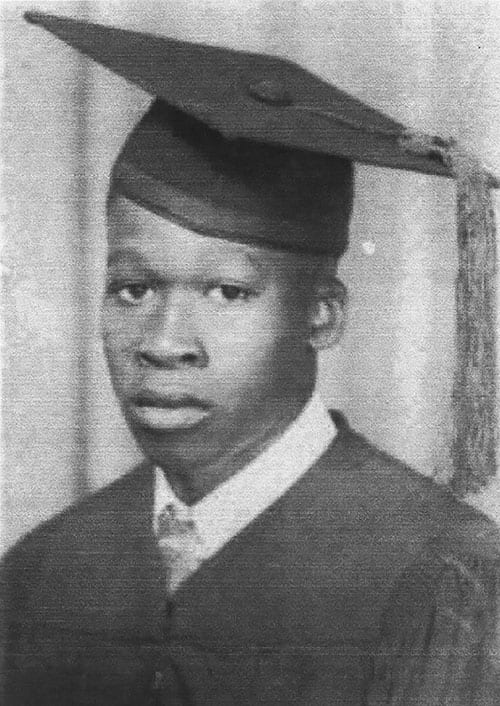

This boy from Port Gibson, Miss. — who became the man of the family when his father left my grandmother, who served in the Korean War and spoke fluent Korean, who left military service and worked in an auto factory in Flint, Mich., eventually becoming a national UAW union officer and credit union board member — gave me what he could, which was a lot.

Despite the lack of any emotional connection to him, I watched him in his side businesses — carpentry and plumbing — and now I am a DIY aficionado that almost lives at Home Depot. He taught me the importance of tipping people in service-related careers, telling me if you can’t afford to tip, you don’t get the service. He taught me how to hold down a household when unexpected events occur and still come out on top. He and Mother both stressed education, and they have three college-educated children.

He tried to impart to me the importance of saving your money, but that is still a work in progress (LOL)!

The only thing he didn’t give me was the love I craved from my father. But as fate or the Universe would have it, my husband’s late father, Melvin W. Craft (and his late mother Lucille) accepted me immediately as a third son, and I got the parenting I needed as an adult.

I also received parenting from some of my friends’ parents (Hendersons, Thompsons, Abrahams, Holyfields, Colemans), so I have no regrets.

For members of the LGBTQ community who have experienced what I just went through or will experience it in the future, I want to leave you with this: Regardless of your family dynamics, family situations that center around your sexual orientation, or challenging steps on your individual journey, know that you are supposed to be HERE. You are not a mistake, no matter what anyone says.

Live your life and live it OUT LOUD. Your life is yours, and this is not a dress rehearsal! Do not waste time trying to love and please people that may not be able to return those affections. It doesn’t mean you love them any less because they are your kin, but don’t lose your life behind it.

I lost a lot of years doing just that and, at points, languishing over the failed relationship between my father and me. And in the end, that wasn’t fair to me.

I matter. And so do you.

Buster Spiller is a happily married, longtime activist and award-winning playwright from Dallas.