Wellesian in his operatic cloaks, Andre Leon Talley, above, transformed the world of fashion.

Feminism, fashion, fear and Fred at the movies

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

If there’s anything recent cultural shifts tell us, it’s that women are entitled to the same respect as their male counterparts. Not just in entertainment, but in crime, too. Take, for instance, Debby Ocean (Sandra Bullock), whose brother Danny was the king of the hip heist. But Debbie and her all-female cohorts gets their share of the booty in Ocean’s Eight, a kinda sequel, kinda reboot of the Clooney-Pitt-et al. franchise of loveable larceners who, felonious intent aside, are scrappy scamps you root for. It’s fully of a piece with the other Steven Soderbergh-directed Ocean’s films — as well as his Out of Sight and Logan Lucky, though this one comes courtesy of Gary Ross (Soderbergh produces, though). The tone is bright and smart, and if the “perfect job” seems to rely too much on luck and coincidence…? Well, it is just a movie. A fun, entertaining, feminist movie.

The target of Debbie’s scheme is a valuable Cartier necklace — not because she hates the jewelry house or the owner of the stones, but just because it’s so valuable. Debbie has a secondary plan, of course — revenge on the man who got her sent away to prison by ratting her out. But it’s not about him so much as her crew of only women — Cate Blanchett, Sarah Paulson, Helena Bonham Carter, Rihanna , Mindy Kaling and Awkwafina — pulling off the impossible crime, making a mint and letting delayed justice be served.

The film is awash in glamour. Instead of being set in the glitzy faux-culture of Las Vegas, Ocean’s Eight takes place in the geographic center of the universe (i.e., Midtown Manhattan) during its peak social event: The Met Gala. You might spend so much time gawking at all the celeb cameos, including Anna Wintour, Zac Posen and Katie Holmes, that you miss a clue or two. Don’t worry, it all works out in the end.

And while you don’t go to this kind of movie for detailed character development, Bullock’s essential earthiness grounds her as a sympathetic if cryptic lead. Meanwhile, the other actresses have plenty of moments to shine, from Rihanna’s surprisingly naturalistic hacker to Carter’s Vivien Westwood kookiness to Anne Hathaway as a vain model easily manipulated into being an unwitting accomplice. Just try not to have a good time.

Ocean’s Eight isn’t the only film coming out this weekend with strong ties to the world of fashion. Andre Leon Talley grew up a fey, flamboyant, gangly black kid in the Jim Crow South more than 60 years ago, and his path could have seemed foretold. He struggled against every disadvantage (race, sexual identity, poverty) except one: Amazing intellect buttressed by unbridled curiosity and ambition. He won a full scholarship to Brown University at a time many blacks in the American South didn’t even have access to higher education. But what really changed the arc of his life — and, in a real sense, all our lives — was when, as a 9-year-old, he discovered Vogue magazine.

He eventually landed there, first as an assistant to Diana Vreeland, then as one of the preeminent style writers of the day under Grace Mirabella and ultimately, as fashion director, second only in power to Anna Wintour.

“He’s the Nelson Mandela of couture, the Kofi Annan of what you’ve got on,” says singer will.i.am. Many others, from Sean Combs to Manolo Blahnik to Valentino, pay Talley homage in The Gospel According to Andre, a documentary about not only the man, but his role in paving the way for fashion-izing black culture and turning the esoteric world of fashion into a platform for social justice — just ask Iman, Naomi, Tyra and countless others.

Now 68 and enormous — not just his always-statuesque frame, covered in elaborate, Wellesian caftans and capes, like Rodin’s monumental bronze sculpture of Balzac come to life, via Jabba the Hut, but in his outsized, operatic personality — Talley reflects on being witness to style history while maintaining connection to his roots.

While fairly traditional in its structure, with tons of archive videos of runways and family photos, as well as contemporary interviews with those in his orbit, it’s the humanity of Talley — represented strongly in his faith, his disappointment at the 2016 election results and his feelings about race that still haunt him — that makes this smart documentary compelling.

Get Out didn’t invent the wildly-successful, low-budget fright fest film, but it did give it a certain credibility as something more than a crackin’ genre film — an award-winning, international sensation that’s a critical darling as well. We’re enjoying a heyday of scares, with It and A Quiet Place also generating buzz and box office. So it might be easy to relegate the latest entry in this category, Hereditary, to just another in a chain of horror hits. But it is so, so much more than that. Hereditary is simply the most unrelenting psychological slow-burn since The Shining.

Mr. Rogers repeatedly shared a footbath with a gay (but closeted) black man on his show, subtly teaching inclusiveness and acceptance.

The genius of most of the film, the feature writing and directing debut of Ari Aster, is that its malevolence comes from all the things you don’t see. Aster doesn’t traffic (much) in jump-from-behind-the-door frights; one of the most intense scenes, in fact, is a five minute, wordless segment one-third of the way in during which the audience knows what has happened but the camera stays on the face of a character not looking at the horror before him. The silences — punctuated by Colin Stetson’s unsettling, industrial but sparingly-used score — build tension as much as the feverish, explosive moments that eventually come.

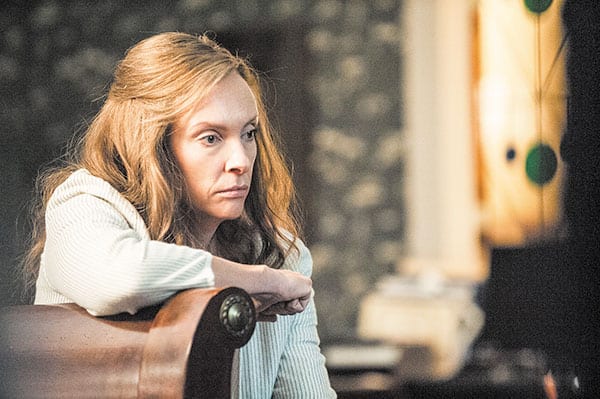

The plot jumps around, so the audience is never fully certain the direction it’s headed. Annie Graham (Toni Collette), a visual artist who makes elaborate miniature tableaux that warrant big gallery exhibitions, is coping with the recent death of her mother, with whom she had a complicated and contentious relationship. Annie’s husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne) is a sturdy doctor who provides just the right amount of moral support. Annie worries that she and maybe her kids will inherit the schizophrenia and bipolar disorders that plagued her family. She surely has reason to worry based upon the behavior of her tween daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro, whose birdlike, beakish face and creepy affect give you the willies every moment she’s onscreen). Annie is racked by guilt, but also craves some kind of closure, which comes, in part, by through bubbly widow in a grief support group (Ann Dowd), who wanders into a spiritualism with a seance that might connect Annie to those she has lost.

If you think you know where this is going, you’re probably wrong. Or at least not totally correct.

Aster is clearly a fanboy of the horror genre, but his allusions are often opaque: A room filled with candles conjures Carrie; Charlie’s centrality suggests Regan from The Exorcist; and there’s that Kubrickian sterility. Indeed, despite its shortcomings (Byrne feels way too old for his role, and his character doesn’t make complete sense), Hereditary joins the likes of those films and the major classics: The Blair Witch Project, The Omen, The Wicker Man.

Toni Collette delivers the female performance of the year so far in the Kubrickian thriller ‘Hereditary.’

And, by the way, The Sixth Sense. The casting of Collette as the mom of teenagers who doesn’t know what’s going hints at that connection, but her performance stands on its own. Looking cyanotic and ravaged, she delivers truly one of the most galvanizing female performances of 2018. (She’s well-matched by Alex Wolff, who plays her son Peter.)

Aster uses ample foreshadowing and leaves breadcrumbs to suggest what’s to come, but I suspect even the savviest viewers still won’t see the exact end coming. A genre film that can still surprise? Get out!

There are probably few people most gay folks could instantly feel less of a connection with than a conservative Republican Methodist minister who speaks in the pattern of a Sunday school teacher. But for a few generations of kids, gay and straight, that’s exactly what Fred Rogers was. His PBS educational children’s series, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, debuted in 1968 at the height of the counterculture, just six months after the Summer of Love. Rogers entered a banal living room, changed into a cardigan and rubber-soled shoes and spoke in a slow tone to preschoolers.

The show was still new when I was its target audience, and I always felt uneasy about what seemed like a condescending, infantilizing manner. At least that’s how I felt until Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, the new documentary from Oscar winner Morgan Neville (20 Feet from Stardom). Oh, I still find Fred Rogers’ persona off-putting and the religious underpinning of his approach unappealing. But in an era of political contrarianism, it’s refreshing to see how we can understand those different from us, and discover common ground.

Among that common ground is how one of the recurring characters on Rogers’ show, the black beat cop Officer Clemmons, was played by a gay man, Francois Clemmons. Clemmons, who is interviewed for this film (Rogers himself died 15 years ago, but appears in rare archive footage), relates how Rogers insisted he stay in the closet if he expected to keep his job… but that he was personally embraced by the man and never judged by him. (Rogers’ widow even explains how the couple had many gay friends, and that Fred felt, as a true Christian, he had to accept all of God’s children.) That was a progressive attitude for the 1970s — one hard to find among many Republicans today — for a man who is credited with single-handedly saving Public Broadcasting, an institution our current administration seeks to gut. Neville’s film thus is not merely a profile of a TV icon, but a clarion cultural document, a call for unity. The show was called Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, but its message was of community.