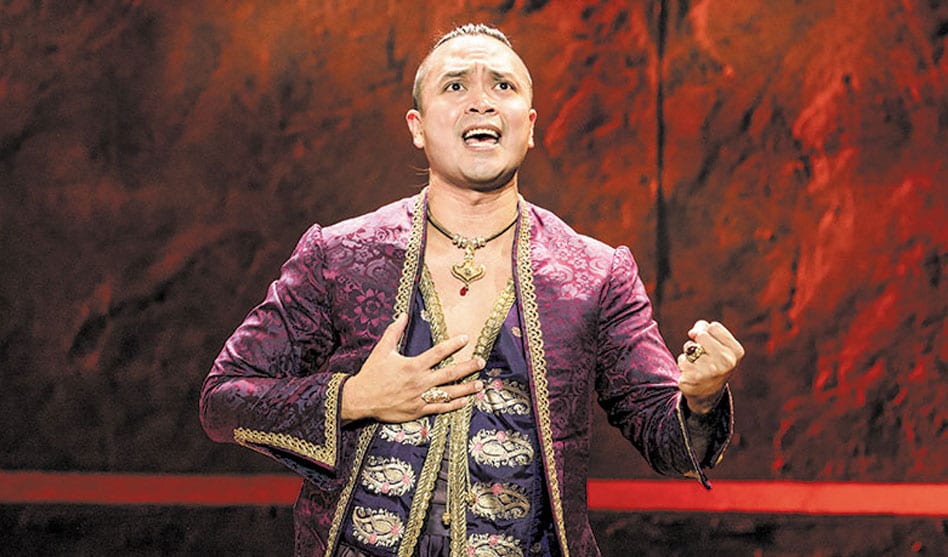

The star of ‘The King & I’ on being out, Asian and visible

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

It’s been more than a decade since Jose Llana made Broadway history as the first speller in the cast of The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee to misspell a word … only to explain, the reason why via one of William Finn’s signature songs: “My Unfortunate Erection,” about how the teen boy he was playing, Chip Tolentino, couldn’t concentrate due to an embarrassing adolescent woody.

It’s been more than a decade since Jose Llana made Broadway history as the first speller in the cast of The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee to misspell a word … only to explain, the reason why via one of William Finn’s signature songs: “My Unfortunate Erection,” about how the teen boy he was playing, Chip Tolentino, couldn’t concentrate due to an embarrassing adolescent woody.

“I always like to bring up that, officially, the title of that song is ‘M.U.E.’ Like [‘Dance 10, Looks 3’ from A Chorus Line], Finn saves the joke,” Llana laughs over the phone. (It’s obvious other reviewers have pointed this out for him before.) “Still, it is one of my signature songs, though obviously one I can’t sing everywhere — it’s a hard song to sing out of context.”

Musically, it might seem a long way to go from frank teenaged angst to the incomparable melodic firepower of Rodgers & Hammerstein… which is exactly what Llana is doing now, starring as the King in the national tour of The King & I. So, which is better as a performer: William Finn or R&H?

“I think you have to like both,” Llana says. “Rodgers & Hammerstein is arguably the foundation of what American musical theater is based on. I grew up watching The Sound of Music and Oklahoma, but when I came out as a senior in high school, one of the first pieces of art that made me think there were other people out there like me was [Finn’s] Falsettos.”

Embracing the classic and the evolutionary, the traditional and the groundbreaking, is nothing unusual for Llana. As a gay Filipino immigrant with an enviable resume, Llana has straddled diverse worlds throughout his career. Before Spelling Bee opened in 2005, he played one of the leads in a tribute concert to Finn … a role not written for an Asian actor. Now, he tours (following a Broadway run) as perhaps the most famous Asian character in theatrical history. And this path has made Llana a fiercely passionate advocate — for race-blind casting, as well as for gay acceptance.

“I’m actually proud [of being an Asian acting in The King & I]. You can’t have a conversation about racial casting in American theater and TV and film without acknowledging that it’s directly related to the history of immigration to this country. I came to the U.S. in 1979 as a 3-year-old, but now there is a much bigger population of a casting pool – bigger than there was in the 1940s and ‘50s when The King & I was cast. That excuse is harder to make today. As much as I love Yul Brynner, I am proud I am playing the King and reclaiming it. It’s empowering.”

And Llana admits that, with all their hummable, orchestral songs and solid book-style musical structure, R&H were vastly ahead of their time as progressive artists: of their output of 11 musicals, fully half deal in some ways with racial and social justice.

“People forget that Rodgers and Hammerstein were both very liberal people for the time period — they were the Lin-Manuel Miranda of the 1950s. Flower Drum Song [set in Chinatown] was their only contemporary show, and they were writing about 1950s San Francisco — let’s talk about racism right now. They [wrote] strong-willed, outspoken women fighting against the norm of acceptable behavior. Bart Sher [the director of this tour] really wanted to bring up feminist tones in our production, because they were there in the script. The song ‘Getting to Know You’ — it’s all about race relations! ‘We don’t know each other, now we’re friends.’ It’s a liberal dream! Tell a story with some catchy tunes, but it’s really about accepting people who are different from us and aren’t necessarily bad. That’s the genius of their work.”

Being out about his ethnicity as well as his orientation is practically a mission for Llana. He fights stereotypes with his art.

“Representation means everything,” he says. “I’ve benefited from open-minded casting directors and directors [open to] non-traditional casting. And I hate it when people use it against us — ‘If you can play Billy Bigelow, then why can’t I play the King of Siam?’ But it’s not the same. The stereotype is that Asians are the polite minority. But every city [we go to], looking out into the audience and seeing young Asian-American kids looking back? It means a lot to see yourself represented onstage.”

Llana, friendly and smart, even welcomes a serious discussion about the generic term Asian when applied to people of different Eastern heritages. For instance, when he and Tony winner Lea Salonga were in Flower Drum Song, they were two Filipinos playing Chinese.

“I welcome that kind of criticism, because it means people are talking about race,” he enthuses. “I’m happy to defend it. People are always guilty of assuming that you have to handle your public with kid gloves. But polite conversation kills opportunity for moral growth. My mom and dad have always been outspoken liberal people. They love having a gay son and an engineer daughter, which is why I am always at the center of uncomfortable conversations!”

So how does he, as an out gay man, feel about “stealing” the role of the uber-hetero King of Siam from a “qualified” straight actor? Llana laughs.

“I have a hard time sleeping at night,” he jokes, “but I manage.”