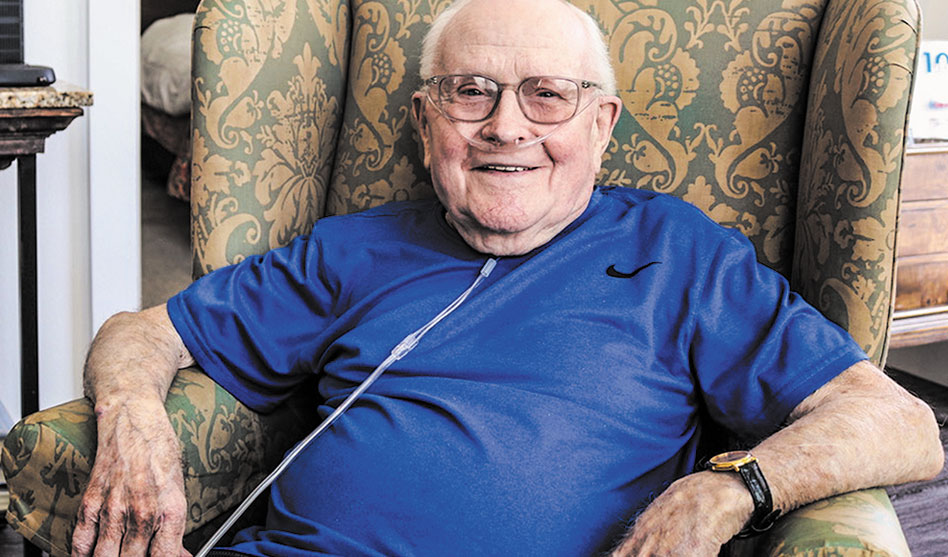

George Harris celebrates his 90th birthday this week. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

George Harris has been a pillar of the Dallas LGBT community since the 1950s

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

When George Harris and Jack Evans became the first couple to legally marry in Dallas County, they had already been together 54 years. That day in 2015, Dallas was the largest metropolitan area in the country to gain marriage equality, and a photo of the couple applying for their marriage license in the County Records Building was printed in newspapers around the world.

Evans passed away a year later, and still, Harris said, “I think about him all the time.”

After his husband’s death, Harris said he found the apartment they shared depressing. So he moved to a new apartment near the American Airlines Center. “I love it here,” he said of the fifth-floor flat that is decorated with awards and accolades the couple won over the years, and with paintings Evans created through the years, including a special one that hangs in the bedroom: It was the last painting Evans did before he died.

“I didn’t plan on living this long,” Harris said this week of his 90th birthday. “What keeps me going are my friends. I have a lunch or dinner every day this week.”

On June 26, 2015, George Harris, left, and Jack Evans became the first same-sex couple legally married in Dallas County

And just because he’s aged, doesn’t make him any less opinionated than he’s always been: “Jack and I always loved our friends and our community,” he said, then quickly added, “And the parade needs to be on Cedar Springs.”

Harris has a stake in the parade. “Alan Ross always called me,” Harris said. Then Harris would always ask Ross, “How much do you need?”

Then he would tell Ross to “ come on down” to pick up a donation that would help bail the parade out of debt.

In talking about Dallas’ LGBTQ history, one memory brought back another for Harris. “Alan Ross? Hell, I knew Frank Caven,” he declared.

“He was a piece of work. He hated drag queens. He’d have the bouncers check their hair for marijuana.”

Harris and Evans both moved to Dallas in the late 1950s.

Evans had been working for Neiman Marcus in Houston. Lawrence Marcus fired him because he couldn’t have a gay man working in his store. But after firing Evans, Marcus asked him to stay on through the holiday season because he was shorthanded, and Evans was a great salesman.

After the Christmas rush, Evans moved to Dallas where he got a job with a savings and loan.

Harris was in the Army in the mid-1950s. After just two weeks of basic training, he became a stenographer. Males stenographers were rare and in demand, and he was assigned to work with a colonel. The officer was sent to Europe, and he offered Harris the opportunity to go overseas with him. Harris declined, and when he was asked where he’d like to serve, he said Washington, D.C., for no particular reason.

So Harris was sent to D.C., and there he was pulled from the Army to work for the CIA. But during his background check, CIA officials realized Harris was gay, and he, along with 27 other gay soldiers, was arrested “like we were a threat to national security,” he said.

That was a terrible time, Harris said. He and the others were held in the basement of a building for months. The prosecutor wanted them to serve time in Fort Leavenworth for falsifying their Army recruitment papers by not marking homosexual on the document. The judge felt differently, though, and gave each of the men a dishonorable discharge.

A friend who picked Harris up from the court told Harris he was going to Dallas the next day. Harris said, “I’ll go with you.”

One of George Harris’ most prized possessions is the letter from President Barack and First Lady Michelle Obama congratulating him and Jack Evans on their marriage

After staying with his friend at his house in Seagoville for a bit, Harris moved into the downtown Dallas YMCA. He described the seven-story building as “Sex, sex, sex. Those Highland Park daddies would flood the place. Cowboys from West Texas. Doctors. Lawyers. W.A. Criswell [the pastor of First Baptist Church]. Don Meredith who came to exercise and for the sauna.”

The Y, nicknamed “the French embassy,” had the only sauna in Dallas at the time.

First Baptist Church eventually bought the place and tore it down, so Harris moved to a room in a house on Bowser Street in Oak Lawn.

Then one day in 1961, Harris was at the Taboo Room, a bar just off Lemmon Avenue across from what is now Whole Foods. He met an antique buyer for Neiman Marcus who was about to go on a European buying trip who invited Harris to a party at his apartment in the Westchester on Lemmon Avenue. That’s where Harris met Evans.

Harris said he when he met Evans, he thought, “This is it.” But Evans wasn’t ready to settle down. So they just dated.

But Harris found himself spending more and more time at Evans’ apartment across from what is now the Health Campus for Resource Center on Reagan at Brown.

“I was determined to settle down,” Harris said. And later that year, he and Evans rented a house together on Monticello at Highway 75.

A couple of years later they bought a house together. But because two men couldn’t be on the same mortgage, Evans took out the loan on the $14,500 house. They renovated it and flipped it.

“We doubled our money,” Harris said. And they made a business of flipping houses. But Evans Harris Real Estate didn’t open until 1978.

“We were the first all gay real estate company in Dallas,” Harris said. In 1991, Evans Harris Real Estate opened an office on Lemmon Avenue next to the Westchester apartments and adjacent to the Taboo Room where the two men first met.

But it wasn’t all good. Harris listed off the names of all the agents who had worked for them, then noted, “They all died from AIDS.”

Lynda Adleta, founder of Adleta Fine Properties, was “crazy about Jack Evans,” Harris said. And when she asked the couple to join her Park Cities sales team, they did.

The two men worked together well as a team, Harris said: “I did the paperwork, and he did the people work.”

The couple retired in 2010, even though “Jack wanted to keep working,” Harris said. But the real estate business had changed; everything had become computerized, and there just wasn’t a place for them anymore, he explained.

But retiring didn’t mean they weren’t still active. After an interview with Dallas Voice when it was suggested they record some of their stories, Evans sent out an email to about 100 friends and suggested they create a group that would archive the history of the Dallas LGBTQ community.

“Will it fly?” he asked in the email.

“Not another damn group!” Harris declared. But it did, indeed, fly, and that was the beginning of The Dallas Way and the LGBTQ archives at University of North Texas.

Together Harris and Evans won Black Tie Dinner’s Kuchling Award and the North Texas LGBT Chamber’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and they were tapped Alan Ross Texas Freedom Parade Pride Honorees.

Harris served on Resource Center’s board for a number of years, and, with John Thomas and others, founded the Stonewall Business Association, the organization that morphed into the North Texas LGBT Chamber of Commerce.

What Harris is most proud of, though, is a letter the couple received from President and Michelle Obama congratulating them on their marriage: “May your love for one another guide you in all you do, and may your bond grow stronger with each passing year,” the Obamas wrote.

Today, more than 60 years after he met the love of his life, and seven years since Evans’ death, Harris obviously still adores his husband. “What a glorious relationship we had,” Harris said.

Have a happy 90th birthday, George.

One can’t think about ever lasting love without thinking of George and Jack. Happy 90th, George. Much love.

What a life and legacy .. Happy Birthday!

I’m sorry for the loss of your amazing husband, but I am in awe of your beautiful life together. Thank you so much for all you’ve done for our community. It can never be repaid back for everything that you’ve done but I am truly grateful and may you live long and healthy life and enjoy this life while we’re still here.

I was honored to know and work for them in the 1980’s and 90’s. Love conquers all. Let their lives be a beacon of hope to all gay people who doubt their self worth.

.