J.W. Lown, who left San Angelo for Mexico 4 years ago to remain with his partner, becomes an advocate for same-sex immigration rights

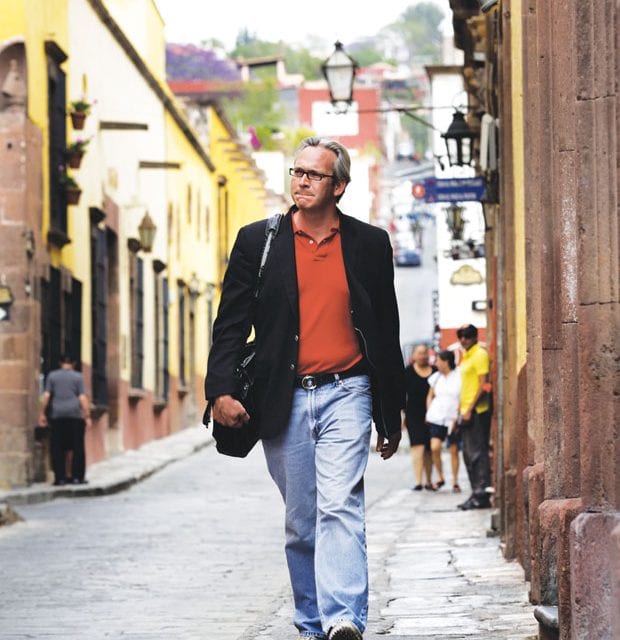

NEW LIFE | Former San Angelo Mayor J.W. Lown walks down a street in the Centro district of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where he sells real estate, on April 10. (Bob Owen/San Antonio Express-News)

JEREMY ROEBUCK | San Antonio Express-News

SAN ANGELO — A secret gnawed at J.W. Lown’s conscience after his six years as mayor of this deeply conservative city on the West Texas plains.

At 32, he began dating a young university student, and their relationship quickly grew serious. The problem? His new love was a man — and an undocumented immigrant.

Advisers pleaded with the mayor to drop the romance. If word got out, it could sink his political career. Even worse, they cautioned, illegally harboring an immigrant could send him to federal prison.

So days after winning re-election to a fourth term, Lown made a drastic decision.

“We just packed up the car, drove for the border and never looked back,” he said. “Just like Thelma and Louise.”

With that choice four years ago, San Angelo lost one of its most popular mayors ever, and Lown — widely viewed as a rising star in West Texas politics — abandoned his rapid ascent. But he followed a path blazed by hundreds of gay Americans each year, who have found that U.S. immigration law offers no easy way for them to live legally with foreign-born partners.

While heterosexual citizens can sponsor spouses for green cards with relative ease, no such option exists for committed same-sex partners. Many move abroad. But few have their choices play out on such a large public stage.

“I could not honestly take the oath of office to uphold the laws of this country and remain in my relationship,’’ Lown said.

In the years since his flight, he sought to avoid the TV news crews and tabloid press that descended on San Angelo, hungry for any detail of the gay mayor and his lover in the heart of conservative Texas.

But now, as debate over immigration policy and same-sex marriage have moved to the national forefront, San Angelo’s runaway mayor has re-emerged, hoping to marshal his past notoriety to influence opinion back home.

“It’s painful to think about — leaving behind my family, leaving behind eight years of building a stellar reputation within my community,” he said in an interview from his new home, San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where he and his partner have settled. “I’m hopeful the country has come to a point that we can have this discussion.’’

Conservative and tolerant

Granting new rights to same-sex couples has emerged as one of the most controversial elements of the immigration reform debate.

President Barack Obama has endorsed including same-sex partners “in permanent relationships’’ among those eligible for spousal green card sponsorship. But key constituencies, including some Republicans and religious groups, describe that plan as a deal-breaker.

Some might view Lown’s recent attempts to enter the fray, including a letter to chief immigration reform opponent U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith, R-San Antonio, as a quixotic effort, given the politically charged debate.

But if anyone stands to sway opinion, it might just be Lown. After all, the residents of San Angelo not only chose him, a gay man, as their mayor, but re-elected him three times.

Lown never spoke openly about sexuality while in office. Though looking back, he said, it had to have been “one of the worst-kept secrets in San Angelo.”

“When you’re 33 and still escorting your sister to every social event in town, people start to wonder,” he said.

Ask residents now, and most will tell you they knew well enough.

“Everybody knew the mayor was gay,” said Jean Rochford as she prepared for a game with one of the city’s many bridge clubs on a recent afternoon.

“And nobody cared,’’ card partner Betty Whitten chimed in.

Still, opinions are slow to change. When a proposition to ban same-sex marriage appeared on the ballot in 2005, 83 percent of the city’s voters supported it. Pundits still rank San Angelo’s U.S. congressional district as one of the most conservative in the nation.

For Greg Gossett, Lown’s former campaign treasurer, the inconsistency isn’t too hard to explain. In a city founded as a small, bone-dry outpost on the Texas frontier, folks have always faced life with a hearty dose of “live and let live,’’ he said.

“Life was tough here, and you had to rely on your neighbors,” he said. “There was a sense of everyone banding together. Even today, people are conservative, but also fairly tolerant.”

That Lown, son of a prominent local foundry owner and an immigrant mother from Mexico City, proved to be a charming and able politician didn’t hurt either.

Joseph Wendell Lown could not have been more different than the bankers, developers and good-ol’-boy types San Angelo was used to sending to City Hall when he first announced intentions to run for the city’s highest office in 2003.

Fresh off a stint with the Peace Corps in Bolivia, the then-26-year-old looked as if he could have walked off the campus of Angelo State University. About the only trait that lent him an air of gravity was a head of prematurely graying hair.

But what Lown lacked in age and familiarity he made up for in a willingness to devote himself to the political grind.

He knocked on doors of seniors, women and Hispanics, groups the old business establishment had long ignored. He attended garden clubs, block parties and dozens of other community events.

And once elected, he rarely let up. He would spend hours in conversation with constituents and later echoed their concerns at City Council meetings, supporter Louise Karona recalled. In one year, he attended nearly 1,600 community events.

“He had this special charisma you don’t find in too many people,’’ she said. “He had a way of making you feel important.’’

Politically, Lown brought a brand of fiscal conservatism and social libertarianism to bear on city management, keeping a tight watch on taxpayer money while promoting the city’s downtown and investment in its infrastructure.

“He was tireless, and people saw that,’’ Gossett said. Eventually, “at his political rallies, you started seeing Republicans next to Democrats, liberals standing with conservatives.”

His passion paid off among voters. After three terms in office, Lown won his last campaign — just days before his departure in 2009 — with an unheard-of 90 percent of the vote.

“Of course, people knew he was gay,” said Mario Castillo, a prominent Washington lobbyist from San Angelo, who became Lown’s political mentor. “But they kept voting for him to be mayor, not the parish priest.”

He added: “As long as they liked what they saw on the ledger sheets, they didn’t much care what was going on between his bedsheets.”

Fleeing the country

But close friends rarely heard Lown discuss much of a social life.

“Occasionally, he would mention how it would be nice to have a dinner conversation with or someone to wake up with and grab breakfast in the morning,” said Charlotte Flowers, a city councilwoman and friend. “But he was so geared toward politics, so focused on his career.”

So when he met and began dating the man who would eventually become his partner in early 2009, he was as shocked as anyone to find himself falling in love.

The man, a then-20-year-old junior studying business at Angelo State, first met the mayor while working on a class assignment. The two hit it off and began to see each other socially.

Lown’s new beau grew up in the Mexican state of Guanajuato and came to Texas in 2004, hoping to pursue an education. And at Angelo State he thrived, becoming a fixture on the dean’s list, studying business and teaching salsa classes on the side.

From the beginning, Lown said, “he was very up-front with me about his legal status.”

Fearing for family members still living illegally in West Texas, the man asked not to be identified in this story.

But while Lown recalled seeing something of himself in the attractive, young striver, his political advisers saw only trouble.

Castillo first heard of the budding romance well into the mayor’s 2009 re-election campaign.

“I made it very clear to J.W. the perils of the situation,’’ he said. If word got out, the relationship could sink Lown politically, or worse, send him to jail.

Lown tried to break it off, but doubt quickly crept in. As supporters celebrated his overwhelming election victory, Lown couldn’t muster much in the way of enthusiasm.

“Finally, it just hit me,” he said. “I couldn’t live my life regretting I never took a chance on love.”

On the morning of May 9, 2009, San Angelo’s newly elected officials gathered at City Hall to be sworn in at the first meeting of their new terms. “Nine o’clock came. Then 10 o’clock came,” said Flowers, the councilwoman. “We were all getting kind of worried. Finally, about an hour later, the city manager broke the news.’’

Lown had fled the country.

Opened minds

Today, Lown’s sprawling ranch house south of San Angelo remains much as he left it four years ago.

Presidential biographies and books of philosophy still cram his bookcases. His bed lies unmade. His closet remains stuffed with abandoned clothes, among them a pair of size-13 work boots.

“They still haven’t found the guy who can fill his shoes,’’ his sister Alicia joked while giving a recent tour.

A persistent rumor heard about town has it that Lown will return any day now to run for his old office.

“If he were to come back,” said Dwain Morrison, one of three actual candidates in May’s mayoral race, “he would beat all of us.”

Despite the town’s conservative politics, San Angelo has rallied around its former mayor.

Drop his name even now and watch as faces light up and questions pour forth asking how he and his partner are doing. During his one visit back to San Angelo — for a friend’s wedding last year — the receiving line at his homecoming party stretched three hours long.

Some even credit Lown with reshaping their political views. Flowers’ husband, a man the councilwoman described as “as red-necked as they come,” no longer makes gay jokes over weekend barbecues. “He’s done a complete 180,” she said. “Without J.W., he still would have been back in his old, closed way of thinking.’’

Back at Jean Rochford’s daily bridge game, similar sentiment has spread among the crowd of players.

“I don’t understand why they can’t just live here together,” she said. “Who are they hurting?’’

Brenda Chapman nodded her head in agreement. “Sometimes when it affects someone you know and respect,” she said, “your conservative views just go right out the window.”

Life in San Miguel

Lown and his partner realize they might never be able to return. Their efforts to find a legal path back have so far have met with disappointment.

Last year, the White House issued an executive order sparing immigrants brought into the country illegally as children from the threat of deportation. Had he stayed put in Texas, Lown’s partner might have qualified.

Recent talk in Washington of overhauling the nation’s immigration system brought more cautious hope. But an immigration reform bill introduced in the U.S. Senate this month makes no mention of visas for same-sex couples.

As it stands now, his partner won’t become eligible for even a tourist visa until 2019.

“You can’t plan a life on a tourist visa,” Lown said. “So, you just block it out and try to press the restart button as best you can.”

Since settling in San Miguel, a colonial tourist haven in the Central Mexican highlands, Lown’s partner has finished his degree. The former mayor now works in real estate and attends classes at a Mexican university.

But even in their new life, signs of Lown’s first love peek through.

At every bar and restaurant he enters, he works the room like he’s running for office, stopping to visit with an endless stream of friends, business contacts and casual acquaintances. At school, a recent lecture on building and maintaining political power drew a wistful look to his eyes.

And so, Lown persists.

On a recent afternoon, he set out to write a lobbying letter to Congressman Smith, who he worked for as a college intern in the late 1990s. Typing from his computer, more than 2,000 miles from Washington, Lown sought to prevail on their past personal connection to sway the lawmaker’s thinking.

“There’s no other place than San Angelo I’d rather be,” he said. “But I have no plans to return again, unless (my partner) can come with me.”

He won over San Angelo. How hard could a congressman be?

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition May 3, 2013.