Emerson Collins: Gay Pride, however celebrated, is nothing to apologize for

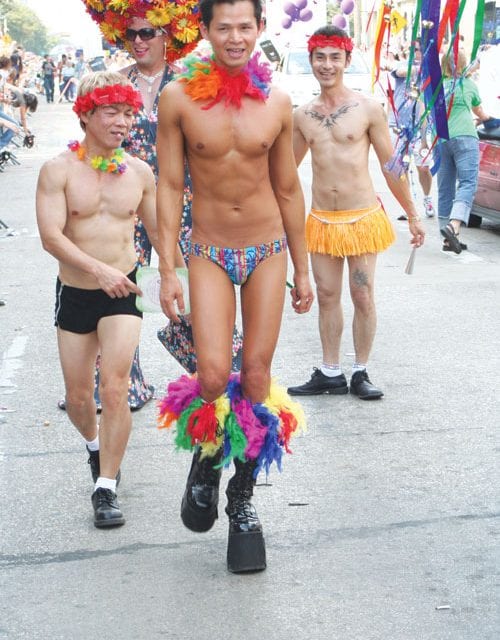

PRIDE CASE STUDY NO. 1 | The barely-clad newbie. bedecked in Speedo and bright smile, is one of the author’s favorite Pride ‘types.’ (Chuck Marcelo/Dallas Voice)

June is Pride Month across the U.S., and the kickoff to a season of Pride. Every weekend from June through September, somewhere, the LGBT community amasses in official events and activities celebrating our diversity. And every year, about the same time, complaints about Pride will begin, too. Everyone has an opinion about what Pride should be — and should not be.

Some of these conversations are incredibly valuable as the big-tent community continues to consider what it is, where it is going and how it should be represented. Each voice contributing to this discussion provides a greater celebration of who and what we are as a collective of varied individuals coming together to celebrate us.

There are important questions that are worth asking in order to define what each community wants and needs Pride to be. What is Pride? Is it a parade? Is it a celebration? Is it a political demonstration? What are we saying — to each other, and to the non-LGBT community? How do we want to present ourselves? Who do we want to represent us? Are we represented?

These are all good questions. Unfortunately, some of the answers are not. The greatest rejection of the very idea of Gay Pride is typically expressed as: “Pride does not represent me.” That’s a valid feeling. It’s the specific objections — and suggested solutions — that so often include judgment of other parts of our community that are problematic.

The main objection is often one based on personal sensibilities — that certain modes of dress and flamboyant presentation become the main images associated with Pride. The go-to examples are often drag queens, go-go boys and “those guys in the assless leather chaps.” The frustration is that these are the visuals that the (mainstream) news media will gravitate toward … and they do not represent all of us.

But let’s acknowledge a basic fact about the news. The goal is to get ratings or page views, and media do so by finding the most sensational images and stories possible. This is not specific to, or targeted at, the LGBT community. Stories about sportsball games show the crazy drunk fans painted in team colors and bellowing nonsensically. Stories about big concerts show the most obsessed fan with the artist’s new album cover tattooed on their arm. Stories about weather catastrophes show the house that is most demolished. That is the nature of modern media. But catering our behavior to the agenda of the news is ridiculous, and self-defeating. Were we to march in Brooks Brothers suits, local TV stations probably wouldn’t even cover us; and if 99 percent were dressed like novitiates in an abbey, the one percent in Speedos will still be the lead photo.

Not for the news coverage, but for ourselves, there are some general guidelines all Prides and attendees should be able to agree upon without controversy.

First off: Don’t break the law. The driving force behind our legislative agenda is to be treated equally under the law in all ways. This means obeying the ones that have nothing to do with being LGBT, regardless of whether we like them or not. If public intoxication and indecent exposure are illegal, that’s your answer. If you do not like a law, work to change it. Flaunting violations of them demeans the importance we give to LGBT legislative successes.

Second: Don’t make a mess. It is embarrassing the amount of trash left in public spaces following large-scale gatherings. This isn’t an LGBT thing, it’s a civilization thing. It should be a personal pride thing. Find a trash can; it’s not rocket science.

Finally, smile at everyone, and cheer for everyone. The LGBT Accountants Association should receive the same whoops, hollers and cheers that the LGBT veterans and the float full of the foam-covered boys from the club receive. The entire point of the celebration aspect should be celebrating us all equally. Appreciating everyone who took the time to be a part of the parade is literally the least you can do.

The second major objection to Pride festivities is rooted in the goal of having Pride be kid-friendly and acceptable to straight allies in attendance. First, what, exactly, does “kid-friendly” even mean — or more directly, what about Pride is not kid-friendly? The semi-nudity? One of the great joys of coming out of hetero-normative, puritanical society is the ability to pull back the curtain on so many cultural and social mores.

Children have access to extreme amounts of unfiltered violence, but the display and celebration of the human body and sexuality may be damaging? Those assless chaps? Literally every person in the world has a butt. What is so scary and scarring about seeing it? What is so incredibly difficult about explaining drag, or leather, or fishnet as a costume of personal expression? How terrifying for children to learn that all the shapes, sizes and colors of the human body are beautiful and that being a sexual being is something to be cherished and celebrated? Stop blaming your own puritanical sexual inhibitions on the children. The kids will be just fine.

I’ll be honest — I have three favorite personalities I see every year at Pride, and they each make me giddy. The first is the Rubenesque lesbian — topless, with duct tape Xs across her areoles. I don’t see the same set every year, but I always see one (or, rather, two). This always makes me smile — for the celebration of her body, for her rejection of objectification, for the casual way her getup says, “I love my body and who I am.” Now, she may just like being kind-of naked, but for a guy who had crazy body issues for years on a long journey to self-love, she makes me feel like we are on the same team of loving ourselves, regardless of external beauty standards. Yes, it is a massive projection on my part; I don’t think she would mind too much.

The second Pride persona I love to see is the newbie. The first-timer. When it’s a boy, he’s often clad in barely-there shorts or swimwear, the result of his recent discovery of brands geared specifically to gay men, where “extra large” means “30 inch waist.” Some version of face paint or makeup is usually beginning to melt down his face and his best girlfriend is being half-dragged through the crowd toward the next, new, exciting, shiny thing.

What I love most about him is the smile from ear to ear that seems impossibly big and permanently attached. The thrill is visceral, radiating from him, and it is a wonderful reminder of the Oz-meets-Club Babylon feeling I had at my first giant gay celebration. I don’t know his story, his journey or how easy or difficult coming out was for him, but I do remember fondly that moment of excitement upon looking up and down a crowded street and seeing my people gathered en masse for the first time. I appreciate him for reminding me of that. For me, Pride is as much about remembering where we have come from as it is a celebration of where we are now.

My final favorite Pride character — and he is the same guy every year — is the gentleman, likely in his 70s, dressed in rainbows from head to toe: A rainbow top hat, a rainbow harness, rainbow polyester assless pants, a rainbow thong and rainbow combat boots. The piece-de-resistance is a set of rainbow butterfly wings. He stands beside the parade route, smiles and waves at everyone who passes.

And I love him for it all — for the outfit, for the freedom evident in it and for the positive energy he gives to anyone who glances his way. He inspires me. When I step outside of the privilege I have for growing up in an era where Pride celebrations are expectedly common annual events, it helps me imagine what the world was like for him. When he was my age, Pride was unimagineable, equality was a pipe dream and there were few if any LGBT clothing and bookstores selling rainbow ensembles. He, and his celebration, reminds me how fortunate I am and how completely I stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before me — people who made even writing this article possible.

Again, I’m projecting, but in doing so, I’m getting out of Pride what I want, and sometimes need.

Each of us has that opportunity. Pride should be what you want it to be, but not at the expense of judging those who express themselves in ways that are different from your self-expression. Wanting to be represented is great; wanting others to not be represented is doing to them exactly what was done to our entire community for so long. Pushing anyone into the shadows because they do not fit your personal narrative makes you no different than those who wish the LGBT community to be silent in the greater segment of American society.

Every Pride march or parade or street party or festival has a process for participating. If you do not see yourself reflected in it, change that. Sign up. Create a float or booth for lesbian doctors, gay plumbers, bisexual teachers, transgender attorneys or whatever specific expression of LGBT you feel does reflect you. If the life you desire is the homosexual equivalent of a heteronormative family, no one should belittle you.

You should be cheered equally if you make a beautiful suburban home float, tastefully decorated by Crate & Barrel as you sit in matching arm chairs with your family in jewel tone cashmere sweaters, flat-front khaki pants and topsiders to wave at the crowd. If that’s you, that’s awesome! Make it happen. Show yourself. Express your LGBT reality by adding your voice to the great cacophonous symphony of the community.

Just do not ask the club kids to put on their clothes, the drag queens to tone it down or the dykes to get off their bikes because “what will the straight neighbors think?” The entire point is that we should not have to care. Any of us. We should be long past the misguided idea that “the more we look like them, the more they will accept us.” Seeking equality does not, and certainly should not, have to look like seeking acceptance. Accepting us or not is on them. Changing who we are to gain that acceptance defeats the entire purpose of being proud of who we are. And being proud of who all of us are.

The overarching theme of modern day Pride may not be as much about political demonstration, but the important message of rejecting judgment should remain clear. “You cannot judge us” is a part of the message Pride sends to non-LGBT society. Not judging each other is even more important. Young, fit gay boys sneering at the appearance of others is just as disgusting as those who wish to hide the porn stars, the drag queens, the gender-nonconforming or the scantily clad at the back of the acceptability bus. Our cries for equality seem hollow and hypocritical if we cannot first accept each other.

The rainbow continues to be symbolically appropriate for Pride, because every shade of every color should be welcome. Denying each other the ability to let whatever version of our freak flag fly that we choose to is really the only thing we should ever have to be ashamed of about Pride. It is telling that in the 1969 proposal for the first Pride demonstration at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile

Organizations, the phrase, “No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration,” was included. If they knew how important unfiltered self-expression was then, long before the LGBT community had gained any measure of visible acceptance, how can we possibly forget the important lesson of allowing every form, version and iteration of personal LGBT Pride to be something we are all proud of now?

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition June 20, 2014.