7 cast recordings to add to your playlist (or not)

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

The Tony Awards were only in June, and already nominated shows have closed and new ones have opened, including some of the bigger, more promising musicals. Last season failed to ignite a runaway smash the way The Book of Mormon, Kinky Boots or Hamilton have done in recent years…. At least until Moulin Rouge! opened eight weeks ago. Still, there has been a resurgence in original cast recordings, particularly of original musicals (only one revival in this list). So here is our roundup of the latest musical scores. Expect to hear most of them on local stages in the coming seasons.

Hadestown

The big dog at the Tonys this year was this allegory, which has been bouncing around as workshops, concept albums and smaller productions for more than a decade. All that tinkering has resulted in a lovely hybrid of Americana and Greek myth — part Porgy & Bess, part Passing Strange, part Delta blues.

In a post-apocalyptic landscape that musically sounds like early 20th century folk music, Orpheus (Reeve Carney) and Euridyce (Eva Noblezada) fall in love, but are also cursed with eternal tragedy. The familiar story is narrated by Hermes (Andre De Shields, whose aching voice cuts into like an emotional buzzsaw), with rhyming couplets in between the down-home, funky-bluegrassy lyrics. The book, music and lyrics are by Anais Mitchell, whose understanding of the rhythms of jazz, R&B and even free verse and the use of slide guitar and woodwinds gives the album a sense for sitting around a campfire at midnight, as if Tom Waits were regaling with stories of our collective past. It’s a hypnotic score and one of the most immersive cast albums of recent vintage.

The Prom

The presence of Beth Leavel — the drowsy chaperone from The Drowsy Chaperone — and a book co-written by Bob Martin might clue you in early about the tone and camp factor of The Prom. Leavel plays a famous, self-important actress named Dee Dee Allen, whose latest show becomes an unexpected flop. She and her costar (Brooke Ashmanskas) decide to take up a cause to humanize themselves and choose the plight of a queer high school student banned from bringing her girlfriend to prom. We’re gonna help that little lesbian whether she wants it or not, the actors proudly sing (while the student opines: Note to self: Don’t be gay in Indiana). Director Casey Nicholaw’s super-gay sensibility (he also did Something Rotten! and Book of Mormon) serves the material perfectly — there’s no such thing as “too big” in a Nicholaw show. The composing team of Matthew Sklar and Chad Beguelin (Elf, The Wedding Singer) imbue every number with as much elbowing to the ribs as a torso can stand. By the time of “The Lady’s Improving,” Leavel’s second-act showstopper, you’ll wanna jump to your feet.

In addition to the ironic indictment of theaterfolk who take up “causes” for “the little people,” it tells a beautiful story of a gay teen romance with smarts and sensitivity. The Prom is up there with Avenue Q and Hairspray for being fun, catchy and subversive simultaneously.

Moulin Rouge! The Musical

Moulin Rouge! The Musical

Baz Luhrmann probably doesn’t get the credit he deserves for transforming the jukebox musical. Although collecting disparate songs in an improvised plot has been around since at least the Gershwins were on the Hit Parade, the idea of magpieing pop, rock, folk and more from different eras and artists and illuminating character as well as story can draw a straight line to Luhrmann’s 2001 film Moulin Rouge. And we have been inundated with patchwork musicals ever since (Motown, Disaster!, Cruel Intentions, Priscilla Queen of the Desert, to name a sparse handful).

Moulin Rouge was among my favorite films of 2001, but when I rewatched it recently, it didn’t hold up as well as I’d hoped. So I was concerned slightly by the prospects of the Broadway version, which opened this summer. And the cast recording proves Luhrmann has captured lightning in a bottle twice.

You can tell that the plot is essentially the same, as is its vibrant energy. (The soundtrack captures an amazing sense of place and interaction.) But while many of the songs that Luhrmann curated two decades ago have remained — “Lady Marmalade,” “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” “Your Song,” “Nature Boy” — he and book writer John Logan recognize that the point of the show (as with his Great Gatsby film adaptation) is that contemporary music conveys a lot of cultural touchstones. It’s the same reason Hamilton feels so immediate with a mixed-race cast, adding an urgency to historical characters. So the inclusion of Katy Perry’s “Firework,” Beyonce’s “Single Ladies,” Pink’s “Raise a Glass,” Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance” and more all but reboot the significance of the show. And the engineering of the album couldn’t be better, nor the vocal performances by Karen Olivo, Aaron Tviet, Danny Burstein as the rest of the cast. What a treat to rediscover this modern classic… made even more modern in this rendition.

Be More Chill

Be More Chill

When Be More Chill opened earlier this year on Broadway — it has since closed — it managed only one Tony nomination, for the score, and you can see why. The songs conjure an updated, adolescent version of Rent: by way of Little Shop of Horrors with a dash of Mean Girls: Outcasts (suburban high school losers, not bohemian 20ish urbanites) trying to find their way in the world against obstacles from the more popular kids. Our hero is Jeremy, a theater dweeb with a crush on Christine, but a bully who denies him self-confidence. Then the bully offers him a secret to popularity: A pill, called a SQUIP, which contains a quantum nano computer that tells the taker how to sound cool. (Basically, the opposite of the Hormone Monster from Big Mouth.)

Joe Iconis’ music is ebullient with a techno influence, his lyrics campy fun if not unavoidable earworms. You can pretty well see where the story is headed (popularity is a drug! SQUIP is an insidious Faustian double-edged sword — it gives what you wish for, and takes away what you need, and Jeremy becomes an insufferable douchebro. But it’s all told with such angst-y good nature, who cares?

Tootsie

David Yazbek has been turning out musical scores at an alarming rate for the last 20 years (five full scores, plus additional music for other shows). But even as occasionally catchy as his songs might be (“Let It Go” from The Full Monty … before Frozen usurped it), his shows (including Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown), have been of middling musical interest. At least they were until his evocative chamber musical, The Band’s Visit, which won him (deservedly) a Tony in 2018.

His quick follow-up, an adaptation of the 1982 drag classic Tootsie, has more in common with his other scores than Band’s, but amped up a bit. The songs are campy and ironic… perhaps not to the level of The Prom, but not bad, though the rhymes can be pretty clunky (especially on a song like “I Like What She’s Doing”). Interestingly, even knowing the plot of the movie — about a failed New York actor who achieves success on a soap opera only after pretending to be a woman — isn’t really detectable just by listening to the songs. In that way, they seem to augment story more than to advance it.

Beetlejuice

Beetlejuice

The trap of Beetlejuice is similar to that of the recent live-action film adaptation of Aladdin: When the secret sauce of the source material is the insane personality and improvisational skills of the central character (Robin Williams, Michael Keaton), trying to recreate such snappy energy is a minefield. And even if you can do it onstage, translating it again for a cast recording, absent the costumes, lighting and physical contortions is yet another bridge to cross … sadly, a bridge too far. Although the score begins with a whiff of Danny Elfman’s sympathetic vibration of Tim Burton’s aesthetic, including Theremin and a silly tone, it quickly devolves into sing-songy melodies and rap where singing would be better; Alex Brightman, who plays Beetlejuice, does not have a mellifluous voice by any definition. One misguided decision? Having the actors sing “The Banana Boat Song” instead of lip-synching to Harry Belafonte’s scratchy vinyl version; it loses its charm and creepiness.) While some numbers, like “No Reason,” capture the oddly ebullient fatalism of Burton, most songs are haunted by the suspicion that they must work better if you could just see the production; but you can’t, and the score alone simply cannot scare up much enthusiasm.

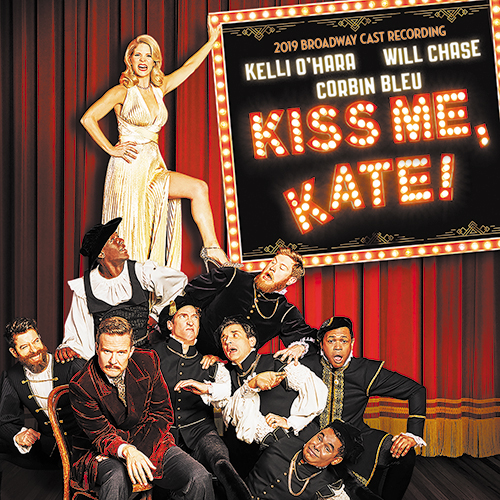

Kiss Me, Kate

Kiss Me, Kate

Moulin Rouge isn’t the only familiar musical to be reworked. Cole Porter was his own jukebox, cobbling shows together from individual songs, until he was tapped for Kiss Me, Kate, and composed all the songs to propel the story. The resulting catalogue — the Viennese waltz “Wunderbar,” the operatic “So In Love Am I,” the comic “Brush Up Your Shakespeare” — became entrenched in the Great American Songbook. The 2019 Broadway revival, with Kelli O’Hara, updated some #MeToo groaners (the title and lyric to “I Am Ashamed that Women Are So Simple” was modified, for instance), but others of Porter’s notorious double entendres remain intact. Is it right that their pronunciation of “Padua” bugs me? Or that you can feel the creakiness of the original, even with the updates? (A joke about the Kinsey Report would have been timely in 1948; today it might go by unnoticed entirely.) Revivals of this type — and I’d include the recent Hello, Dolly — are probably better served by seeing them live. But, I mean, Cole Porter…? You could do worse.