TRAC gives former foster child a chance to make the world, and the system better

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

nash@dallasvoice.com

The average young adult who goes into foster care enters the system between the ages of 11 and 15, and goes through an average of eight placements and five Child Protective Services caseworkers, according to Madeline Reedy, director of the Transition Resource Action Center, a program of CitySquare (a nonprofit assisting those living in poverty) that helps young adults aging out of the foster care system adapt to life on their own.

“These kids enter care at a time when they are already rebelling and learning new and different things,” Reedy said. “Most of them come from a negative background, and they are having to tell their story to someone new every year. They are moving every six months, all over the state and even out of the state sometimes.

“That’s a lot of trauma — trauma on top of trauma. It’s a very difficult life, and it impacts their brain development.”

TRAC, Reedy said, works with those young men and women as they are leaving the foster care system, a “one-stop shop” for the services they need to adjust: drop-in centers that provide crisis intervention counseling and a safe place for them to stay during the day, life coaching, after-care case management, job training, help finding work, and help finding somewhere to live.

Reedy said that TRAC officials “guesstimate” that about 30 to 33 percent of the young people participating in TRAC are LGBT, although “it’s hard to track that. You do the intake when you first meet them, and there’s no rapport there yet. And they’ve been conditioned not to tell anyone [that they are LGBT]. Really, it’s not important to us except that it’s important for us to know how to best serve these people and the safest place for them to be.”

But, Reedy added, those who are LGBT “do sometimes have a harder time of it, especially when it comes to work. We like to think discrimination doesn’t happen, but it does happen in the workplace. That adds additional barriers, and it impacts their mental health in a different way. They struggle with depression, with self confidence. We try to refer them to support groups with like-minded peer groups.”

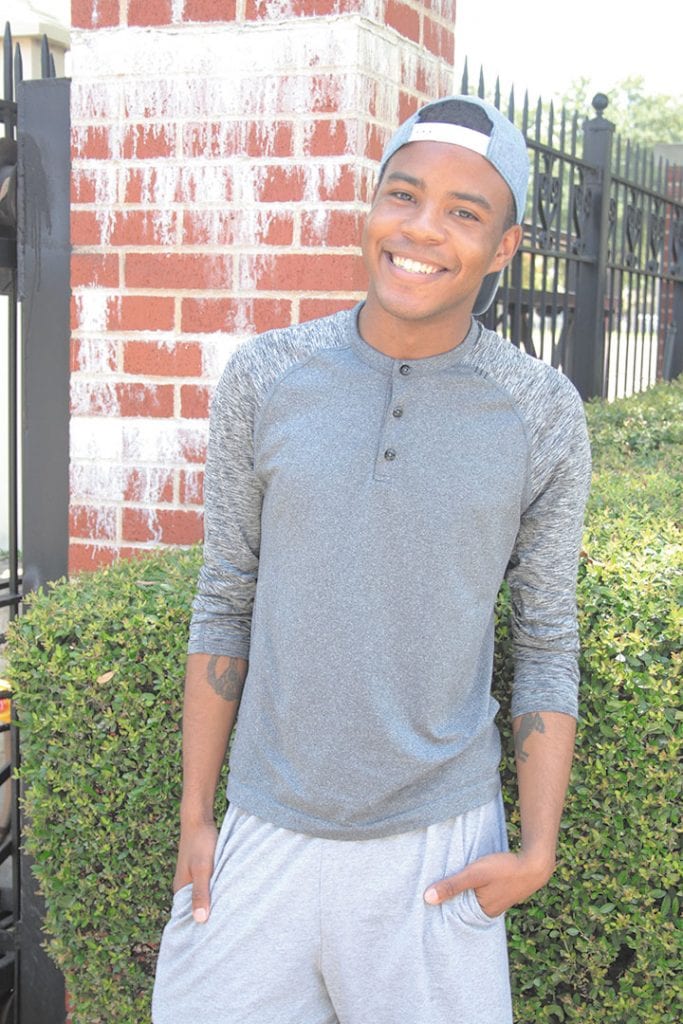

James

James Givens is one of the young gay men who has turned to TRAC for help. He was 15 when he and his older brother first entered the foster care system. He was shifted around to three different foster homes before, at age 18, he opted to shift to the state’s supervised independent living program.

They went in to foster care, he said, because “We called CPS on ourselves. My grandmother and my dad [who lived in Houston] weren’t really able to provide food and other things that we needed. There were a lot of drug influences around us.”

But, said James, who has been openly gay since before he entered the foster care system, the final straw came when their grandmother called police on Marty, the man who had been helping care for him and his brother.

Marty, he explained, was a friend of their grandmother’s who was also openly gay. James was about 12, he said, when Marty started helping care for him and his brother.

The two boys started spending more and more time with Marty, grateful for the stability he offered. “But I guess Grandma got jealous or something; I guess she thought Marty was getting all the attention from us she wanted,” James said. “She’s really not a judgmental woman, but maybe she got the wrong idea.”

She started contacting Marty’s neighbors, telling them he was a pedophile and a sex offender, James said. Ultimately, one day when the boys were at Marty’s house, she called police, and showed up outside the house herself, yelling at Marty to “give me my grandkids back,” and asking him, “Why are you taking their affection away from me?” James said.

Because of that, he said, “We got pissed off.” James said that their plan when they called CPS was that the state would take them away from their grandmother and father, and then their grandmother and father would agree to let Marty adopt them. The state, though, refused.

“The state wouldn’t let him adopt us because he was gay,” James said. “That’s the whole reason we went into foster care, so he could adopt us, but a white gay guy adopting two black kids — the state wouldn’t let that happen.”

James and his brother, who are black, were fostered first with a white family in Houston. James said that although his brother was treated well there, he and his first foster mother clashed from the start.

“She didn’t like that I was gay,” he explained. “She told me I had a demon in me; she said some really hateful things. I was like, OK crazy Christian lady. Whatever. I guess you could say we got off to a bad start.”

James and his brother were both kicked out, though, after the foster parents discovered that his brother and their daughter had begun a relationship. “I guess that was too much for them,” he said.

Their second foster home was headed up by a Nigerian woman who at first “treated us like humans, not just a paycheck. She told me that she didn’t care about my sexuality. She said, ‘As long as you’re going to school and working to better yourself, I don’t care.’ We got off to a good start.

“But the longer you live with someone, the more you start to see their true colors,” James continued. “I know I wasn’t some perfect angel; I was certainly the more emotional one between me and my brother. I guess there was something in my character; she just didn’t like the person I was.”

One night James, 16 at the time, came home about 30 minutes late after being out with friends. That led to an argument, in which the woman called him “a bitch” and James “cussed her out.” After six months, James and his brother were on their way to a new home, this time in Dallas.

James’ brother aged out of foster care and chose to move back to Houston to live with Marty. James said his own immaturity, led to an argument with his foster mother, later, and at 18, although he could have stayed there until he was 21, James chose to move into the supervised independent living dorm, then later into his own apartment with partially subsidized rent.

He wanted to move back to Houston with Marty, he said, but by that time Marty had hit on some financial hard times and was unable to help. James said his own immaturity led to him “messing up” his chance with the SIL program. He headed to Houston and was staying with his brother, who lived with his girlfriend and her mother. But that didn’t last either, and James found himself living with a friend and her mother in a car. Thankfully, he had stayed in contact with his CPS caseworker, and that’s who connected him with TRAC.

“Before, I took all my anger out on the world. I felt like my family didn’t care; my father didn’t care enough to change. And I don’t even know my mother [who lives in Detroit]; when we first went into foster care, the caseworker contacted people on that side of the family, but they wouldn’t take us,” James said.

“In foster care, you can feel neglected. I felt like my family didn’t care, either,” he said. Finding TRAC was like starting over. I was living in a car and hadn’t bathed in two weeks, and then I had a chance to start over. I was like that 15-year-old kid again, only this time, I was more adult. I needed to get my life together.”

Today, James has his own apartment and a job in a restaurant. He’s looking for a second job and intends to start school at Mountain View College in the fall. He said he wants to get his degree and become a social worker so that he can one day work to make the foster care system better.

And someday, he added, he hopes to find a partner and create a home for children — his own and foster children.

“I don’t want my kids to ever feel there’s not someone there for them,” he said. “I don’t want them to be scared to talk to me about anything. I want to be a really good father for them; I want to be the father my father wasn’t. TRAC is giving me the chance to do that, to have that.”

Singer/actress Jennifer Hudson is coming to Dallas Saturday, Sept. 9, to perform in A Night to Remember 2017, the annual fundraising gala benefitting CitySquare. The concert takes place at the Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House at the AT&T Performing Arts Center.

For details and tickets, visit CitySquare.org. Tickets start at $50.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 28, 2017.